SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Aloja Santos, 49, has been waking up earlier than the rest of her neighbors in Barangay Looc in Dumaguete for the past five years to collect garbage from one house to the next.

Houses should have already segregated their wastes overnight, or early in the morning, or else Santos or the other waste collectors will not get them.

Despite the discrimination they face for doing a “dirty” job, Santos knows her job is important.

“Para sa akin po napamahal ko na po yung trabaho ko,” Aloja told Rappler in an interview. “Masaya po ako nakakatulong po ako sa aming barangay, sa aming komunidad.”

(For me I have learned to love my work. I am happy that I get to help my barangay, my community.)

Waste workers – garbage collectors, waste pickers, segregators, recyclers – across the country remain mostly invisible, especially those working in the informal sectors. They receive much lesser wages. Santos, for example, said she gets P2,000 per month. Obviously, it was not enough to support five children and her seven grandkids.

Though their work exposes them to possible contaminants and hazardous substances on the daily, they do not have health benefits and insurance. Even the costs of bike maintenance fall on their shoulders, said Santos.

Santos said she hopes the national government would see them and hear their pleas. Waste workers might be invisible, but once there is no one to clean up the streets and collect waste, the consequences would be plain as day.

Forming an alliance, fighting for labor rights

This is the reason why waste workers decided to form the first-ever national alliance of waste workers.

“Kasi nang nasa loob po kami ng limang taon ng pagseserbisyo namin sa barangay, parang ‘di kami napansin, ‘di kami nabigyan ng mga pangangailangan namin, mga benepisyo at saka kahit suporta man lang,” said Santos.

(Within the five years that we’ve served our barangay, it seemed like we were not noticed, we were not given our needs or benefits or any support.)

The Philippine National Waste Workers Association (PNWWA) was born on February 2024, and Santos currently serves as president. It has ten member associations from Dumaguete, Malabon, Navotas, Taguig, Siquijor, San Fernando in Pampanga, Legazpi in Albay, Calapan in Oriental Mindoro, and San Jose Sico in Batangas.

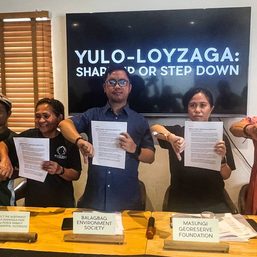

The formation of the alliance is called by groups as a “significant move for labor rights and environmental justice.”

One of the major efforts of PNWWA as early as now is a draft magna carta enumerating their rights, which they are lobbying to legislators, “marking a historic and unified call for the recognition of their rights.”

This includes their demands for a minimum wage, protection from occupational and health hazards, and inclusion in the solid waste management boards in their villages and municipalities.

Keeping waste workers’ best interests at heart can push forward the implementation of the solid waste management law, said Raphaelo Villavicencio of Mother Earth Foundation (MEF).

“If they’re given the right support by the government and concerned agencies, they would be more effective and their work would contribute to the implementation of RA 9003,” Villavicencio told Rappler in Filipino.

Republic Act No. 9003 or the Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000 mandates a comprehensive waste management program and the adoption of best environmental practices to reduce waste.

Going zero waste

Waste workers are just one part of the equation towards zero waste.

To achieve zero waste, huge companies must restructure their production and distribution systems and redesign products and packaging.

The whole life cycle of a product needs to be accounted for. What kind of packaging can degrade easily? What are the distribution systems in markets and groceries that could eliminate the use of plastic? How can we create less waste?

In communities, materials recovery facilities (MRF) designed to receive, sort, process, and store compostable and recyclable materials reduce waste that end up in landfills. An MRF could show how a circular economy works on a smaller scale.

Local governments employ waste workers in MRFs. For example, Santos is now employed in the MRF of her barangay after five years as a collector.

Contrary to what people think when they hear about recovery facilities, Ranz Lebria of Mother Earth Foundation told Rappler that these spaces should be green.

“It should be a garden,” said Lebria in Filipino. “Not just a dump site for waste, but like a mini park or an ecopark.”

A materials recovery facility in Dampalit, Malabon, experiments with different types of composting. Soil, sawdust, vegetable and fruit cuttings are jammed inside pipes, pots, and pants. How fast waste decomposes depends on the type of composting employed.

Herbal and ornamental plants grow in patches beside the compost heaps. Meanwhile, the kitchen in the facility gets its fuel from the methane released from the biodigester. This is where the facility workers cook their meals throughout the day.

Flaviano Romero, 72, had been working as a caretaker in the Dampalit materials recovery facility for four years. Before that, he was a pedicab driver. He gets P3,000 a month and goes home at 7 or 8 pm at night.

Whatever way one decides to compost organic waste, the practice helps divert waste from landfills. An effective recovery facility at the local level could “decentralize” waste management and change the habits of people and a community.

“It’s hard at first because we’ve gotten used to a linear system where we collect and dump, right?” said Villavicencio in Filipino. “Unlike in a decentralized system, you not only filter waste, you can also monitor waste segregation.”

Villavicencio said waste workers are the backbone of this system, as they also make waste management more economical for their villages and cities. Trips of waste trucks, for example, are reduced, cutting fuel and maintenance costs.

“And then you’ll see that not all collection vehicles are motorized,” said Villavicencio. “You have bikes, side carts, push carts, which have less carbon footprint, less fuel emission. Then of course, less maintenance costs.”

The changes in their barangay were considerable since the zero waste movement was introduced to them, said Santos.

The streets are now cleaner. There are changes in habits, however minuscule. Santos herself learned a lot and changed jobs from purok leader to collector and now as a caretaker in their MRF.

Santos said she, along with other waste workers, has taught people how to properly segregate and dispose of their trash. Despite the measly income, these things have made her stay.

“‘Pag mahal mo ang trabaho mo, tatagal ka.” (If you love your job, you will stay.) – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Demystifying net-zero and climate reporting in the Philippines](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/TL-climate-reporting-philippines-May-3-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] In a changing climate, how do we ensure safety and health at work?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/Climate-change-safety-workers-April-25-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.