SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

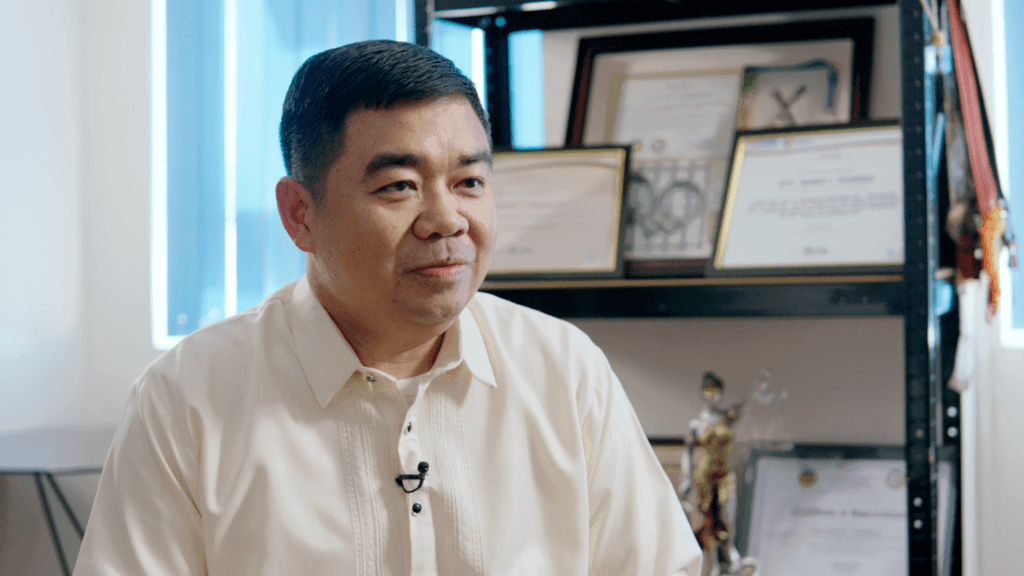

Perfectly ironed sleeves, partnered with black pants and shoes. Towering height, calming but commanding voice. These things can easily be associated with Mario Dionisio Jr., a Public Attorney’s Office (PAO) lawyer.

Dionisio spends most of his time inside their office located in one of the top floors of Justice Cecilia Muñoz Palma Hall in the Quezon City hall compound. He heads the PAO Quezon City district.

As the chief, Dionisio oversees 87 lawyers under his supervision. He ensures that their PAO lawyers have the eagerness to help their indigent clients. Dionisio said they cannot let their guards down and be lax, otherwise, their case loads would pile up.

“We have to be proactive enough kung paano namin matutulungan ‘yong korte sa disposal ng mga kaso (on how we can help courts dispose of cases),” Dionisio told Rappler in an interview.

Dionisio has been with PAO, the government’s primary legal office that provides free legal assistance to indigent Filipinos, for the last 16 years. However, it took him just as long to get there, if not more.

Living in two worlds

To afford sending himself to law school, Dionisio worked as a security guard.

All by himself, he enrolled at the Manuel L. Quezon University School of Law. While studying for most of the day, Dionisio worked as a security guard for establishments during the night. Time management was key.

His day back then usually started at 11 am. After preparing for school, Dionisio would travel to Quiapo, Manila, from his rented room in Cubao, Quezon City, to study. He said he typically stayed in the library from 12 noon to 5 pm to read.

His classes would end at 9:30 pm, so he had 30 minutes to travel from school to work. While on duty, Dionisio made sure the establishment he was guarding was safe. On the side, he studied some of the required readings and cases for school.

At 6 am the next day his shift would end, giving him only around five hours to sleep before preparing again for school. Dionisio survived the first few years of law school in this set-up, but things became much harder later on.

He narrated how his class schedule, on top of varying assignments for his security guard job, took a toll on him. It was difficult for him, he said, since there was no permanent establishment he was assigned to guard. He jumped from one location to another, until the assignments became much farther.

Financial difficulty was also another challenge for Dionisio. He could not afford to buy law books, so he made sure he spent time inside the school library. While there, Dionisio said he would write in a small notebook the pertinent provisions that he needed to memorize. He also photocopied some of the books, so he had copies of the cases he needed to read.

“‘Yon lang ‘yong naging paraan ko kung paano ako makapag-aral doon sa mga cases na in-assign. You have to be ready for the recitation, eh hindi naman po puwedeng wala kang nabasa at all (That was my way to study the assigned cases for school. You have to be ready for recitation, you cannot go to school without reading anything at all),” he told Rappler.

When he was in fourth year, he quit his security guard job, tried his luck, and applied for a job in a government agency. The National Tax Research Center (NTRC), under the Department of Finance, opened its doors to him and hired him.

From little town with big dreams

Although he grew up in idyllic Aklan province, Dionisio knew at a young age his life would not experience the same green pastures if he did not persevere. He was still an infant when his father died, so Dionisio said his grandparents took care of him. His mother transferred to Manila to work as a domestic helper, leaving Dionisio and his siblings in Aklan.

Due to poverty, he and his two siblings did not grow up together; a typical set-up for underprivileged families. As he remained with their grandparents, his other sibling was taken by their mother’s second cousin, while the other was taken care of by their uncle.

He studied hard and finished high school on time. The problem was, his mother told him she could not support his tertiary education because their eldest sibling was still studying at the time. “Probinsiya” (province) culture, Dionisio said, as some families in the countryside can only support one college student at a time, if none at all.

Dionisio knew he needed to do something. He inquired about schools that offered scholarships.

Fortunately, he was admitted by the Northwestern Visayan Colleges in Kalibo as a scholar. Since the condition for his scholarship was to maintain good grades, Dionisio said he studied really hard. After four years, he graduated cum laude with a Bachelor of Science degree in Criminology.

After graduating, Dionisio flew to Manila to apply as a cop in Camp Bagong Diwa. The Philippine National Police rejected him because he was not yet 21 years old at that time. He said he could not return to the province because there were less opportunities there. He decided to apply for a security guard post, and shortly after, decided to enroll in law school.

The rest was history: “Sobrang laki ng pagkakaiba ng buhay ko noon at buhay ko ngayon. Actually, ‘yong mga kakilala ko sa probinsiya, nagugulat nga sila na abogado ka na pala. Hindi nila iniisip ‘yon na magiging abogado ako kasi nga sino ba naman [kami], wala namang kakayahan ‘yung pamilya, ‘di ba?”

(There’s a big difference between my life then and now. Actually, those people I know from the province were surprised to learn that I am now a lawyer. It did not occur to them that I would be a lawyer because I came from humble beginnings, right?)

Second time’s the charm

After hurdling law school, Dionisio did not immediately become a lawyer as he flunked the Bar exams on his first try.

“No’ng time na hindi ako pumasa sa Bar exams, iniyakan ko ‘yon eh. Sabi ko kay Lord, ‘Ipasa mo lang ako, Lord at magsisilbi talaga ako sa bayan at ipapangako ko sa Iyo, I want to have a covenant with you na gagawin ko yung nararapat: ang tumulong sa mga mahihirap,'” Dionisio said.

(When I did not pass the Bar Exams, I cried. I told the Lord, “Please allow me to pass, Lord, and I will serve the country, and I promise you, I want to have a covenant with you that I will do what’s right: help the poor.)

On his second try, he passed the 2006 Bar exams. The results were released in 2007. Dionisio said he was sure God was with him because his application with PAO went smoothly. Of the big bunch of applicants who sought to enter the office, he was the only one picked for the vacancy in PAO Manila.

Another thing was, when he was still applying to be a PAO lawyer, a multinational company offered him a job and he was told he could start immediately for the corporation. For Dionisio, it was a test, a temptation. He followed his heart and kept his promise; he turned down the corporate job even though he was not yet hired for PAO at that time.

He left his job at the NTRC to transfer to PAO in 2007. Public lawyering was indeed challenging, he said, because of the workload and low pay of PAO lawyers back then.

“Tapos there was a time nga na tatlong courts ang hawak ko. Lagare ako umaga-hapon, then every day mayroong hearing (And there was a time that I handled three courts. I worked from morning until afternoon, every day there was a hearing),” he said.

After years of working as a PAO lawyer, he was promoted to division head. Later on, he was also picked to become assistant district head. In 2019, he was chosen to lead PAO Manila as its district head, before he was transferred to Quezon City in late 2023.

Life as a public lawyer

Just like other public lawyers, Dionisio has a fair share of threats. At the height of the drug war, he held a case involving a police officer. He would travel all the way from Manila to Angeles in Pampanga to attend court proceedings and to his client’s needs.

Dionisio shared that every time he traveled, there was constant fear that he felt, especially since police were implicated in some cases. The last straw was when he received death threats, he said, so he asked the PAO to remove him from the case.

“Actually, lagi namang nando’n ‘yong panganib na ‘yon, lalo sa aming mga abogado. Kaya lang, siyempre, doon pumapasok ‘yong paniniwala ko sa Diyos. Doon pumapasok ‘yong panalangin ko na every day, pagbangon ko pa lang sa umaga, humihingi na ako ng guidance (Actually, the threat is always there, especially to us lawyers. But, of course, that’s where your faith in God comes in. I pray every day, from the moment I wake up, I already ask for guidance),” Dionisio said.

But for Dionisio, the most memorable case he has handled was one involving a child in conflict with the law (CICL). Back in the day, Dionisio said he was assigned to handle a case of a CICL accused of frustrated homicide. With Dionisio’s assistance, authorities decided to sanction the child with diversion and put him under the custody of nongovernment organization, Association Compassion Asian Youth, Inc. for reformation.

Dionisio said under a sanction of diversion, a CICL is handed a diversion contract containing all the terms and conditions he or she needs to comply with. Once the CICL has been reformed and has satisfied all the terms and conditions, the child can be discharged. The case will also be sealed permanently, Dionisio added.

The PAO lawyer said his CICL client is now an aircraft mechanic. Every time his client would be invited to share his experience as one of the models and evidence of the effectiveness of the juvenile justice system, the former CICL would always acknowledge Dionisio as the PAO lawyer who changed his life.

“Napaka-fulfilling ang trabaho ng isang PAO lawyer. At hindi mapapalitan at hindi mapapantayan ng salapi ‘yong pakiramdam na ‘yon na nakatulong ka sa mga tao, na ikaw ‘yong naging instrumento kung paano sila nakalagpas doon sa legal challenges ng mga tao, kung ano na problema ang kinasasadlakan nila. Hindi ‘yon mapapalitan ng pera,” Dionisio said.

(The job of a PAO lawyer is fulfilling. Money can’t buy that fulfillment you feel when you were able to help people, when you became the instrument for their getting past their legal challenges and whatever problem they were embroiled in. You can’t exchange those for money.)

“‘Yon ‘yong dapat na magiging driving force ng mga aplikante o nagnanais na pumasok sa PAO (This should be the driving force for wanting to be a part of PAO). You should have the heart to help. You should have the compassion to help the poor, the indigent, the marginalized.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.