SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

My friends often told me I looked like a turtle during our university days.

There I was working towards a chemistry degree, going around the campus with my heavy backpack, which almost always contained thick science textbooks. The books made my back hurt a lot, yes, but I treated them as my security blanket.

Textbooks are complete and detailed; they’re much easier to understand than our lectures that had impossibly compressed topics. When things got difficult to understand in the classroom (which happened all the time), I flipped through my book’s pages, looking for clarity.

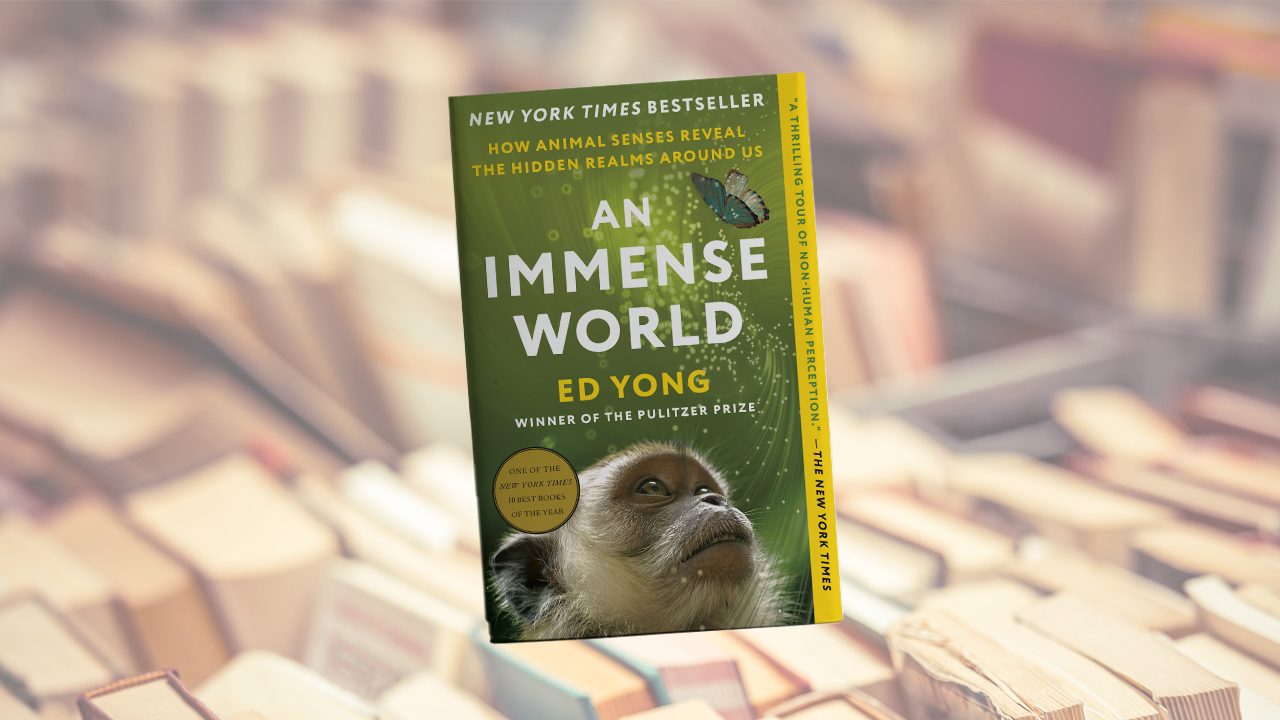

Reading Ed Yong’s An Immense World nostalgically reminded me of the big fat science textbooks that I lugged around for years. In thirteen chapters, Yong gives clarity to the worlds of other animals, carefully explaining each sense — like sight, smell, and taste — that has so far been discovered in all known species.

Ed Yong is a science journalist and a Pulitzer winner for his coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic. But in this book, he tells stories of countless scientists and their experiments — mostly sensory biologists who dedicated their life’s work to understanding how animals sense their worlds.

But Yong uses less images than in textbooks, and in turn, more imagery (the book’s introduction was such a pleasure), less scientific terms (the author was apologetic), less numbers, and (thank God) zero equations.

In the process, Yong gives us a treat: leading us into worlds beyond what our eyes can see, taking the route of other species’ senses.

Trapped in our own world

Describing the sensory worlds of other animals was no easy feat. Yong could have made a documentary instead like most features on animals. But that would defeat the purpose of the book: to look beyond the primary sense of humans, which is our sight.

Yong invites us to travel the world beyond our human senses. He describes this as visiting parallel universes and alternate realities. But to me, it was also like going into another dimension, or at least the attempt to.

As species living in a three-dimensional space, we can never know what it would be like to live in the (hypothetical) fourth dimension and to fully see four-dimensional objects. In the same way, we can never sense the world how other species sense it. But we can try.

The book begins – and intelligently so – with the sensory world of dogs, man’s best friend. With dogs having been domesticated for so long, we think we already know them well enough. But we always forget that dogs primarily perceive the world not by sight but by smell.

We often prevent our dogs from taking pauses and detours during walks. Doing so deprives them of exploring interesting smells and enjoying their own sensory worlds — proof of our entrapment in our own primary sense of sight. It’s like stopping a human friend from appreciating nice views.

To further drive this point home, Yong brings up our use of the English language, where we often use visual words like in I see your point and we share the same view. Futures are either bright or dark. We are oblivious to things in our blind spots.

A similar thing interestingly happens in our understanding of colors.

I have studied colors most extensively in my physics and chemistry classes. And in those classes, we learned to categorize the different existing colors under visible light, which is a part of a larger range of radiation called the electromagnetic spectrum.

But scientists have discovered that other species like birds and bees see other colors under ultraviolet, another part of the spectrum beyond visible light. Though visible to other species, we categorize ultraviolet separately from visible light, because it is invisible to us.

For so long, physicists and chemists – and myself – have been trying to understand the world trapped in our own sense of sight. With Yong’s book, I realized that through the senses of other species, biology allows us to see beyond what is visible to us humans, and in turn allows us to see worlds beyond ours – a mind-blowing realization for a science nerd like me.

Thrilled by the scientific method

To my delight, Yong let his readers live vicariously through the scientists he spoke with, who shared their experiments and discoveries with him. But the author tries his best to exclude the draggy and nitty gritty part of experiments.

Perhaps, as he was a science student himself, he knew this would give readers a chance to enjoy the scientific method (I, indeed, enjoyed it), and allow them to share excitement in the scientists’ Eureka moments.

I particularly appreciated the parts in the book where a scientist says, “they’re misunderstood,” when referring to a species they were studying, like spiders and bats commonly perceived as villains – proof that scientists are passionate about what they do. (I say the same thing with my favorite species – the sharks.)

And my wonderment peaked at the times when scientists learned something new – like why we can’t seem to catch flies; how migratory birds know exactly where to go; and why we have not one, but two nostrils, and how it’s the same reason why snakes have forked tongues.

And that’s to cite just a few of the questions answered in the book.

Yong discusses many other scientific facts and discoveries, citing several scientists and experiments, so much so that the book has filled forty-five pages for bibliography. (In my experience, academic papers’ bibliographies usually fill around three pages – seven pages is already a lot.)

But I can say, Yong’s book doesn’t aim to just overwhelm readers with information, but allows us to enjoy and appreciate vast worlds beyond our sensory bubbles.

It seeks to make us realize that no species is above or below another, that in peeking into the sensory worlds of animals, we see that there is no superiority or inferiority, but only diversity. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Time Trowel] There is more to archaeology than Indiana Jones’ pistol and whip](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/12/tl-timetrowel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=245px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.