SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

After years of marginalization and government neglect, a son of Mindanao is finally gaining a foothold in Metro Manila.

After years of marginalization and government neglect, a son of Mindanao is finally gaining a foothold in Metro Manila.

In an earlier Pulse Asia survey, Davao City Mayor Rodrigo “Digong” Duterte emerged as the most preferred candidate for president in the National Capital Region (NCR).

The poll, which was conducted on November 11 to 12, showed the tough-talking local official beating 4 other presidential hopefuls with 34%. It also showed Duterte overtaking former front-runner Senator Grace Poe, whose numbers had dropped to 26% from a high of 31% last September 2015. While the more recent surveys show his rating sliding down, Duterte remains a serious contender – a fact that is prompting a lot of people to wonder why.

Columnist Antonio Montalvan attributes the “Duterte phenomenon” to widespread public frustration over the “systematic thievery by government officials” and the “endless, divisive bickering among politicians.” For this reason, Duterte supporters see him as the only alternative candidate in 2016 – a “savior” whose tough stance on criminality can “overhaul the government and create a system that is hostile to corruption.”

But how accurate is this image of Mayor Duterte? How radically different is he from the other presidentiables? And what assurances can we have that change will indeed be forthcoming under a Digong presidency?

To answer these questions, we shall take a look at some of the major assertions that the Duterte campaign has been making, and analyze whether there is actual evidence to back up these claims.

Claim No. 1: Digong is not part of the elite

In her opinion column for a daily broadsheet, journalist Carmen Pedrosa described Duterte as “a poor man (who) had governed Davao well,” as opposed to Roxas who is “both a political and wealthy oligarch.” And this image of Digong as a political outsider has been cultivated, not only by his supporters but by Duterte himself, who has repeatedly blamed the elites of Manila for the country’s continued impoverishment.

Speaking with Rappler’s Maria Ressa last October, Duterte said that Philippine politics is largely “decided by two ruling elites,” particularly “the sugar block of the South and the sugar block of Central Luzon.”

And in keeping with his non-elite persona, Mayor Duterte leads a very modest lifestyle with hardly any hint of luxury, except for his personal collection of cheap spy novels and unbranded shoes. But to claim that the current Davao mayor was “poor” with no previous political connection simply has no basis in reality whatsoever.

In fact, the Duterte family is closely related to the Duranos and Almendrases, which are two of the most powerful political clans in Cebu province. Digong’s own father, Vicente Duterte, was even at one point mayor of Danao City, before moving to Davao where he served as governor from 1959 to 1965. The son eventually followed in the footsteps of the senior Duterte – becoming mayor of Davao City for more than two decades.

But while it is undeniable that Digong has done so much for Davao, the length of his stay has also allowed him to marginalize the opposition and solidify the Duterte dynasty.

His brother Benjamin, for example, was a one-time councilor of Davao City. The current vice mayor, on the other hand, is Duterte’s son Paolo. And when Digong temporarily vacated the mayoralty post in 2010, he was succeeded by his eldest daughter Inday Sara, who is now eyeing a second term. It is no surprise, therefore, that Duterte is not in favor of the Anti-Political Dynasty bill, which he claims, could narrow the electorate’s choice and curtail freedom of expression.

Of course, Duterte deserves to be praised for his open criticism of the rulers in Manila. Unfortunately, he sees no reason for curbing dynastic power, which is one of the enduring hallmarks of elite rule in the Philippines.

Claim No. 2: Digong brought development to Davao City

In July 2014, the Facebook group Rodrigo Duterte for President posted a statement crediting Mayor Duterte’s leadership style for “transform(ing) Davao into an award winning city” and for its subsequent economic boom.

Former North Cotabato governor and Duterte supporter Manny Piñol made a similar pitch, by arguing that Digong’s leadership skill was pivotal in Davao’s transition from “one of the most violent places in the whole country” to a truly vibrant and progressive city.

While the importance of Duterte’s role should not be discounted, his supporters however are presenting a very simplistic explanation for Davao’s development. By focusing on Digong’s leadership qualities and personal attributes, other equally significant factors are either neglected or ignored. In fact, the specific geography of Davao is hardly mentioned in any of the discussions.

Most people, for instance, fail to realize that the said city has the busiest airport in Mindanao – the Francisco Bangoy International Airport – which began operations as early as the 1940s. It also has the Port of Davao, which has modern facilities capable of handling major cargo trans-shipment. Davao also happens to be the country’s largest city in terms of geographic size, with a total land area of 2,400 square kilometers – 67% of which is devoted to agricultural production.

Comparatively speaking, it is like having in one location Manila’s port area and Pasay’s NAIA terminals, in addition to fertile farmlands more than double the size of NCR. With these resources and facilities at its disposal, it is but natural for Davao to develop into the major commercial and cultural hub that it is now, regardless of who is City Hall’s actual occupant.

Secondly, while Davao’s calm and peaceful environment enable businesses to thrive, the city government itself is not yet fully self-reliant since it is still heavily dependent on its Internal Revenue Allocation (IRA).

According to the Department of Finance (DoF), from 2010 to 2012, approximately 60% of Davao City’s total budget was drawn from its IRA, which means that the local government has yet to maximize the available revenue sources of the city. And though most local government units (LGUs) remain heavily dependent on their IRA, they are nonetheless encouraged to become more self-sufficient since it is indicative of good planning and sound fiscal management.

Of course, such allegations do not negate the significant achievements that Davao has attained in the past 3 decades. It does, however, put things in proper perspective by also highlighting the difficulties that the city continues to face even up to this day.

Claim No. 3: In Davao, no one is above the law

When asked by Maria Ressa, “what made you so successful in Davao,” Duterte’s reply was both swift and straight-to-the-point: “(We) just follow the law, and if the policy is there, we honor it. And that’s it.”

At first glance, this statement seems to hold water, especially since Davao has enacted a number of progressive ordinances that are being implemented by the city government. Some of these local legislations include a total firecracker ban; a no-smoking policy in all public places; and a 30-kph speed limit to reduce vehicular accidents.

In addition, the city government has also passed the Women Development Code, which aims “to uphold the rights of women and the belief in their worth and dignity as human beings” and the Anti-Discrimination Ordinance (Ordinance No. 0417-12), which penalizes any form of discrimination “on the basis of national or ethnic origin, religious affiliation or belief, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, descent, (and) race, or color of the skin.”

So far, so good.

But central to the idea of rule of law is a related concept called due process, which is guaranteed in Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution. In fact, due process is so sacrosanct that any violation of it carries severe legal repercussions. Unfortunately, Mayor Duterte had admitted on several occasions liquidating alleged “criminals” without any legal formalities whatsoever.

During the same interview with Maria Ressa for instance, Digong openly declared that he had killed at 3 people in the last 3 months since October. He also downplayed a recent warning by Amnesty International regarding his human rights record, saying, “700 daw ang pinatay ko? Nagkulang ho sila sa kuwenta… Mga 1,700 (I killed 700? They underestimated the figures…It’s around 1,700).”

But in spite of these statements, no case has ever been filed against Duterte. This, as expected, has caused frustration among human rights groups, which lament the government’s inaction on the issue despite their repeated calls for a thorough investigation.

In response, the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) has announced it will soon create a special team that will investigate Mayor Duterte’s alleged involvement in extrajudicial killings. It is uncertain, however, if the probe will ever prosper since the CHR’s mandate is recommendatory in nature, having no prosecutory power of its own.

Claim No. 4: Digong brought peace and order to Davao City

Without doubt, Duterte’s growing attraction among voters is based on his tough stance on criminality. As one overseas Filipino worker told Rappler’s Pia Ranada, Digong’s brand of leadership is what the country needs, adding that, “he killed only criminals, drug lords, (and) the corrupt.”

It is also a sentiment that is shared by most Dabawenyos. For as any frequent visitor to Davao City would attest, residents are quick to stress how proud they are of their city and how safe they truly feel under Rodrigo Duterte. And such perception is not without basis.

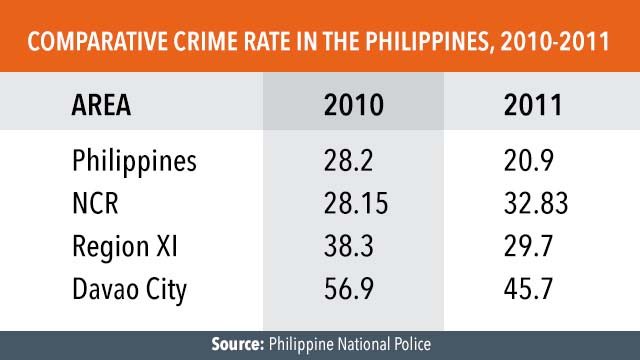

In just one year alone, Davao was able to reduce its crime rate by 20%* – from 56.9 per 100,000 population in 2010 to 45.7 in 2011. During the same period, Metro Manila’s crime rate increased significantly from 28.15 in 2010 to 38.83 the following year.

These numbers, however, also indicate that while Davao City’s peace and order campaign has been noteworthy, its actual crime rate is still higher than the national average of 28.2 in 2010 and 20.9 in 2011.

Davao City even exceeded the crime rate in Region XI where it is located. According to the Philippine National Police (PNP), Region XI recorded a crime rate of 38.3 in 2010 and 29.7 in 2011. Seen from a macro perspective, one could conclude that Davao City’s crime rate is significantly higher compared to other areas in the Philippines.

The Davao City Police Office (DCPO) has defended its performance by claiming that most of the incidents reported in Davao were non-index crimes. Late last year, for example, the DCPO reacted to Mar Roxas’ statement citing a Philippine National Police (PNP) report indicating that Davao had logged a crime volume of 18,119 in 2014, making it the city with the fourth highest number of crime incidents in the Philippines.

In a Facebook post, the Davao police tried to refute this claim by saying that, “out of the 18,119, only 6,548 (36%) were attributed to index crimes, or crimes against persons and properties,” while “the remaining 11,571 (64%) were attributed to non-index crimes.”

They then proceeded to define non-index crimes as “police-initiated operations that yielded positive results especially on anti-drugs and other special laws.”

So what is the Davao police actually saying? The implications are chilling.

Simply put, 64% of the crime incidents in Davao are actually “police operations” which, if interpreted in the light of reported human rights violations, may be understood as the killing or harassment of suspected criminals. If this is the case, then it also implies that the targets are typically poor with no property whatsoever.

By eliminating the city’s underclass, Davao remains safe. Visitors can walk around without any fear because out of the average 1,500 crime incidents per month, there is only a 36% chance (540 incidences in a month) of being a victim of petty crime. Meanwhile, we can comfortably ignore the street urchin and petty thief since their lack of property effectively deprives them of any voice in public discourse.

Yes, there’s a heavy price to pay for maintaining peace and order in Davao City. Fortunately, it’s not the middle class that is forced to carry that burden.

Claim No. 5: Digong can replicate what he has done in Davao nationwide

There is a shared assumption among Duterte supporters that he will replicate whatever he has done in Davao on a nationwide scale if ever he is elected president. This was clearly expressed by Manny Piñol when he described Duterte as “the only presidential candidate who could impose discipline and enforce the law as proven by his achievements in Davao City.”

Though powerful, this assumption however ignores the specific political context that allowed Duterte to come to power 3 decades earlier. Now known as a bustling and dynamic city of 1.4 million people, Davao was a totally different city during the 1980s.

At that time, the place was overrun by communist partisans who fought for control of the streets against government troops and civilian militias. This began in 1982 when armed communists belonging to the New People’s Army (NPA) began moving into Agdao – Davao City’s sprawling urban slum that was home to more than 120,000 residents.

With Agdao as their base of operations, the NPA began attacking military and police personnel, including suspected government informers. In just two years’ time, the communists were able to gain effective control of Agdao earning the monicker “Nicaragdao,” after the Latin American country of Nicaragua, where the radical leftist Sandinista movement took power in 1979.

To counter the NPA threat, Wilfredo “Baby” Aquino formed the infamous vigilante squad Alsa Masa (Masses Arise) in early 1984. After a brief hiatus, the group was later reorganized in April 1986 by former communist sympathizer Rolando “Boy Ponsa” Cagay.

Alsa Masa’s revival was triggered by the execution of Victorio Lamorena – a friend of Cagay who, the NPAs believed, was a government spy. What followed was a brutal fight for control over Agdao and the rest of Davao City that left more than 900 people dead by the end of 1986.

With no end to the killings in sight, Dabawenyos entered into a Hobbesian social contract with Duterte, which allowed him to rule with an iron-fist in exchange for social peace and personal security. In other words, Digong was the man that Davao precisely needed at a time of extreme political violence.

When he first assumed office in 1988, the new mayor had to deal, not only with petty thieves and criminal gangs, but with armed political groups who were ideologically motivated and fighting for power. Duterte, therefore, is a product of a specific historical context that may no longer sway for the rest of the country.

If we are then to elect Digong to the presidency, we must first ask ourselves the following: how different is present-day Philippines from Davao City of the 1980s? Are we facing unmitigated political violence on the streets? Is there a complete breakdown of law and order throughout the country? Are the NPAs at the outskirts of Manila, ready to pounce on the nation’s capital and launch their final assault on Malacañang?

We must thoroughly reflect on these questions before we decide, in the words of Thomas Hobbes, to “lay down this right to all things; and be contented with so much liberty against other men as he would allow other men against himself.” – Rappler.com

*Editor’s Note: A previous version of this story referred to Region “XI” as Region “IX.” This has been corrected. Also, the writers previously indicated that Davao was able to reduce its crime rate by 80% when this was supposed to be 20%.

Francis Isaac is currently in Japan as a graduate exchange student in Osaka University. Joy Aceron is program director at the Ateneo School of Government directing Political Democracy and Reforms (PODER) and Government Watch (G-Watch).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.