SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

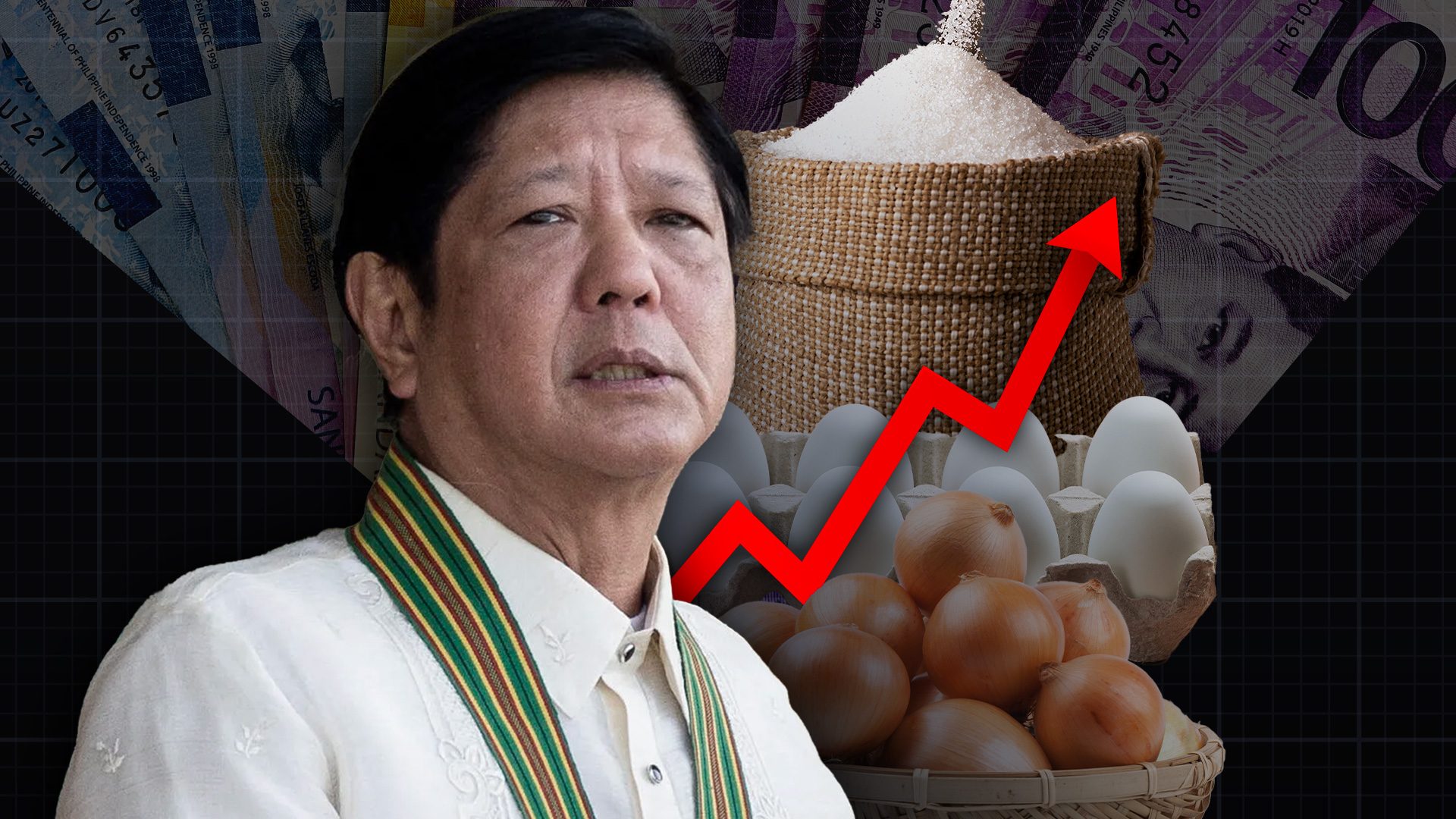

MANILA, Philippines – It’s been about a year since President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. first took up the challenge of revamping the Department of Agriculture (DA) as its secretary. And so far, he’s determined to cling on, repeatedly saying that he isn’t done “fixing” the DA – putting in “structural changes” and “guaranteeing” sufficient food supply and affordable food prices.

“So, hangga’t matapos natin ‘yun (until we’re done with that), I suppose you will just have to put up with me as the DA secretary,” Marcos told reporters on June 16.

Marcos’ move to lead the DA himself seemed to signal that agriculture – a sector that had long been neglected – was now the priority.

“By choosing to be the concurrent secretary of agriculture, it set the right policy direction that this government is giving special attention to the agriculture sector,” Jayson Cainglet, executive director of Samahang Industriya ng Agrikultura (SINAG), told Rappler on Saturday, June 24.

“The local agriculture industry was given renewed hope, though guarded and cautious.”

That hope, however, has been quickly tested. Since Marcos took office, crisis after crisis has rocked the department. The price of sugar was the first to soar, then onions, then eggs. Soon after, hearings in both the House and Senate have dug up alleged cartels controlling the sugar and onion trade.

Through it all, Filipinos have suffered under rates of inflation not seen in 14 years. The World Bank also warned that “the recent rise in food prices threatens the gains the country has made in combatting malnutrition and stunting” as Filipinos on the margins further struggled to afford a healthy diet.

Rappler quantified just how bad things had gotten. Using data from the DA’s daily price monitoring in Metro Manila markets, we tracked the price of agricultural commodities from January 2022 to the present. And the result was telling: prices of several kitchen staples – onions, sugar, and eggs, in particular – have spiked, while other commodities have experienced swings in prices more volatile than before. Scroll through the full charts below.

So, what caused the problems that the President faced in his first year as the concurrent agriculture secretary?

Many layers of the onion mess

About half a year since Marcos took over, the DA faced its biggest challenge so far: controlling the meteoric rise of onion prices. In January 2023, a kilo of onions could set one back as much as P600, way higher than the P90 per kilo in June 2022.

That’s more than a 560% increase – bad enough to garner the country international infamy.

A Senate probe into the volatile onion prices pinned the problem on miscalculations in demand and supply, late imports, smuggling, and a lack of crucial cold storage facilities.

Because onions are usually harvested only once a year between February and April, supply must be stored in cold storage facilities. Ideally, traders place these crops in cold storage to last until the next harvest, with stocks being trickled into the market as needed.

The supply of onions in cold storage, however, began to thin out by the end of the year. But the government refused to bolster stocks with timely importation, saying that it wanted to protect farmers who planted in the offseason.

With supplies running low, the traders who controlled the cold storages began to take advantage. They jacked up prices and made a profit. Consumers paid the price, and farmers got none of the money.

Mismanagement had been the culprit. After all, the country didn’t lack in produce. During harvest season, the supply of onions overflowed and literally wasted away as farmers could not access any cold storage facilities, which could have kept crops fresh for months.

Romel Calingasan, the municipal agriculturist of San Jose, Occidental Mindoro, painted a visceral picture in a Senate hearing: “Marami pong mga sibuyas ang nagkandabulukan, itinapon sa mga tabi ng kalsada, sa mga gilid ng ilog, na kung saan po talaga pong sobrang panghihinayang ang amin pong naramdaman kasi po talagang pinagkagastusan ng aming mga magsasaka ‘yan.”

(A lot of onions were rotting, thrown to the roadsides, to the riversides. We felt so much regret for all that were spent by our farmers.)

This onion crisis may not have gotten as much attention as it should have since the President had to attend to other matters. For instance, he opted to attend the World Economic Forum in the exclusive Alpine town of Davos, Switzerland during his eighth foreign trip, where he was pitching his other priority project – the controversial Maharlika Investment Fund.

Meanwhile, back in the country, his department was scrambling to control the situation. The DA had worked to raid a few warehouses and cold storages that were squirreling away onions, and the Bureau of Customs had managed to seize about 987 metric tons of smuggled crops. But some senators dismissed these actions as “irrelevant,” asking instead why no big-time smugglers had been convicted in the six years since the Anti-Agricultural Smuggling Act had taken effect.

When the DA finally did act, it also fumbled with the timing of its imports. The agency approved the importation of onions early in 2023. However, farmers’ groups feared that the arrival of these onions would flood the market at the same time that local onions were to be harvested. And that was what happened, as traders used the “import card” as a bargaining chip to buy onions from farmers at an unlivable price.

This “open import policy” of the government continued to disrupt the country’s agriculture production system, according to Raul Montemayor, national manager of the Federation of Free Farmers Cooperatives Incorporated (FFFCI).

“[It] discourages farmers from planting – leading to seasonal gluts and low farmgate prices at harvest time, then shortages a few months thereafter – and induces speculative behavior among traders because imports have an unpredictable impact on supply and prices. Smuggling, misdeclaration and undervaluation of imports exacerbate the problem,” Montemayor told Rappler on Friday, June 23.

But a problematic import policy wasn’t the only problem when it came to onions. It turns out an onion cartel may also be behind the “artificial” surge in prices, according to findings of the House committee on agriculture and food.

Lilia Cruz – dubbed the “onion queen” – was said to have set up the Philippine Vegetable Importers, Exporters and Vendors Association (PhilVIEVA) as a way to control the supply of onions in the country. Trading firms, importation firms, cold storage warehouses, and a trucking company have all been linked to PhilVIEVA.

Cruz would use PhilVIEVA and other companies to buy onions at a low price, store them in cold storages, and control when the stocks were to be released. Cruz was also alleged to have monopolized the importation of onions.

“Kung sa unang hearing, si Leah Cruz ay denial queen, by hearing number 9, para sa amin, siya ang undisputed sibuyas queen,” said Marikina 2nd District Representative Stella Quimbo, who also called on the National Bureau of Investigation and Philippine Competition Commission to “expose the onion cartel.”

(If in the first hearing, Leah Cruz was the denial queen, by hearing number 9, we concluded that she was the undisputed onion queen.)

Sugar cartel’s sweet scheme

Cartels, it seemed, weren’t unique to the onion industry; they found a spot in sugar too.

The sugar crisis first became evident in 2022, when the price of refined sugar soared 40% from about P70 per kilo in June to past P100 per kilo in August. During this time, Coke, Pepsi, and RC Cola confirmed that the country was facing a sugar shortage. Months later, soft drinks sold for double the price or disappeared from shelves altogether.

In response, the government tried to temper the rise in prices with importation – except not everyone agreed. In mid-2022, the Sugar Regulatory Administration (SRA) Sugar Order Number 4, which bore Marcos’ signature, supposedly approved the importation of 300,000 metric tons of sugar to address soaring market prices. However, Malacañang later denied that Marcos had signed the order – a pronouncement that eventually led to the resignation of top DA and SRA officials.

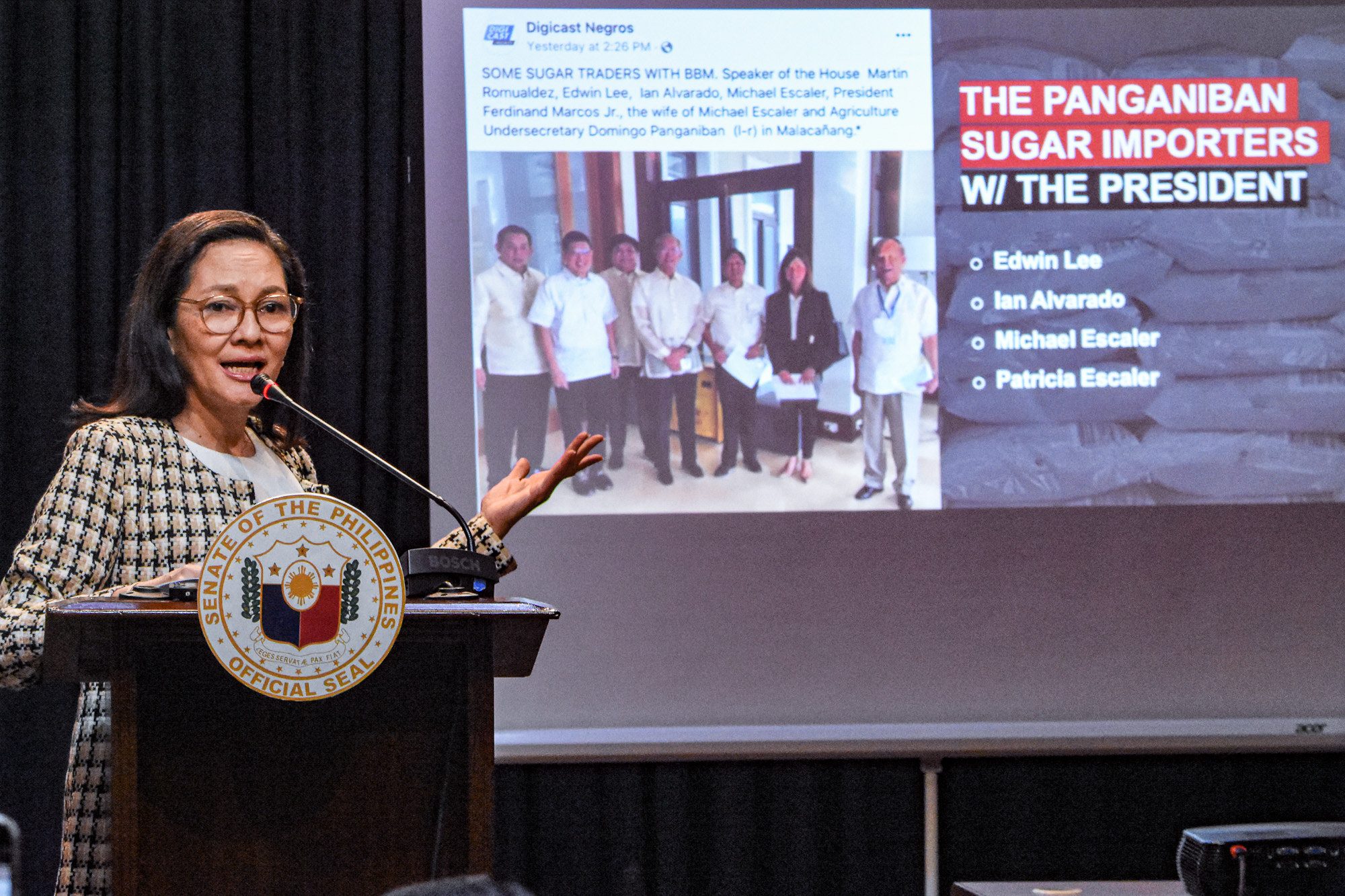

Since then, the mess devolved further, as opposition senator Risa Hontiveros pointed out that just three sugar importers “favored” by the government had been granted specific allocations to import sugar in the hundreds of thousands of metric tons. Historically, she said, importers were only allowed around 10,000 metric to 20,000 metric tons each.

“This is not just a state-sponsored formation of a cartel,” Hontiveros said on March 21. “It is a cartel that generates super profits, none of which will go to the National Treasury.”

Citing unnamed sources, the senator alleged that some of the importers were imposing an additional “super profit” of P24 per kilo, raising the price of sugar for everyone.

Hontiveros also showed a photo of the sugar importers posing beside President Marcos and Senior Agriculture Undersecretary Domingo Panganiban, who had greenlit the sugar order favoring them.

“It is favored and cartel-like. You need to open the importation to all qualified importers in a fair and transparent setting,” SINAG executive director Cainglet told Rappler. “The government is not a mafia that can favor anyone in any transaction.”

When the Senate blue ribbon committee did summon several Cabinet members on May 8, they didn’t show up, leading to the postponement of the probe due to the absence of “vital witnesses.” Panganiban was among those witnesses.

When the committee met again on May 23, Panganiban admitted that it was President Marcos who issued the directive, saying: “Let’s import.” This marked the first time that a resource person in the hearing directly attributed the order to the President.

But after senators grilled the undersecretary on who chose the three importers and why more weren’t invited in the spirit of competition, Panganiban failed to give any straight answers. He admitted that he was not actually knowledgeable about sugar importation since he focused on agricultural production when he was DA chief in previous administrations.

During the hearing, Executive Secretary Lucas Bersamin also defended the actions of the government. Earlier, on January 13, Bersamin had issued a memorandum, by authority of the President, to allow the importation of 450,000 MT of sugar.

“We confirm that the importation was legitimate and fully authorized by the government. The importation was not an effort at cartelization, nor was it about government smuggling of sugar,” said Bersamin. (READ: EXPLAINER: What happened during the sugar crisis under the Marcos dictatorship?)

‘Omelet inflation crisis’

The average Filipino kitchen faced yet another crisis early in 2023. After onions and sugar, the price of eggs also climbed by more than 40%. In June 2022, the per-piece cost of eggs had only been P6; a few months later in January, it had reached about P8.50.

What caused the spike in price? Gregorio San Diego, chair of the United Broilers Raisers Association, said one factor could be higher feed costs. Producers typically spend P5 per chicken for feeds. In January, feed prices went up to as high as P19.

But there was also the issue of middlemen raising their cut of the profit. San Diego said that there was an “oversupply” of eggs. He also noted that typically, retailers only add a few centavos to the farmgate price, which ranged from P6.70 to P7.20 a piece. But eggs had reached nearly P10 per piece in some Metro Manila markets in January, suggesting that retailers could be widening their margins.

Cainglet also said that the “spike in egg prices highlighted the disconnect between farmgate prices and retail prices.” He added that some egg producers had even sold below the cost of production because of the oversupply, and yet, retail prices continued to climb.

“This should be the focus in the coming months: addressing the skewed value chain across commodities that only favor traders, viajeros, and importers – to the detriment of producers and consumers,” Cainglet told Rappler.

New leadership needed

After the DA under Marcos had come off such a rocky start, some senators called for the President to pass on the department’s leadership to a full-time agriculture secretary – one capable of handling the “agricultural crisis” head on.

“Panahon na rin siguro talaga na magkaroon ng DA secretary na aako sa kawalan ng action sa agricultural crisis na ito. Asukal noong una; sibuyas naman ngayon. I-he-hearing ‘ata natin lahat ng kailangan sa kusina,” Senator Grace Poe said in a Senate hearing on the onion crisis.

(It’s probably time to have a DA secretary who will take responsibility over the lack of action in this agricultural crisis. Before it was sugar; now, it’s onions. We’ll end up having a hearing for everything in the kitchen.)

Senate Minority Leader Koko Pimentel agreed, saying that the President had “nothing to lose” by appointing a DA secretary, since he could continue making agriculture his priority even if he wasn’t its head.

Meanwhile, farmers’ groups turned their attention to the bureaucracy and its layers of leadership.

“The DA needs a drastic change in leadership because there is very little initiative to innovate and change the way things are being done,” FFFCI national manager Montemayor told Rappler. “There has been no major improvement in the bureaucracy; in fact, now, there appears to be two heads of the agency – Usec Panganiban for non-rice and [Leocadio] Sebastian for rice – leading to confusion and factionalism within the agency.”

“Wala masyadong (There is little) creativeness and initiative, sad to say. There are good and promising people there, but these are the people who don’t get promoted because they are a threat to their bosses who are comfortable with the status quo. So, a major overhaul is really needed,” he added.

In Marcos’ first 30 days as agriculture chief, he directed the agency to boost production of rice, corn, vegetables, pork, and poultry. He also emphasized the need to “reconstruct” agricultural value chains to grow farmers’ income.

SINAG executive director Cainglet said that in Marcos’ first State of the Nation Address, he also focused on “increasing productivity, lowering cost of production, and strengthening the value chain.” However, these weren’t all going exactly as planned.

“The marching order is clear; unfortunately, may mga (there are parts) lost in translation in implementation – deliberate or otherwise – within DA and the continuing resistance of our economic managers to support local agriculture,” Cainglet said.

In the meantime, the other steps to “fixing” the agriculture value chain – such as coming up with a master plan of farm-to-market roads and increasing post-harvest facilities – have yet to fully materialize.

“There has been no major change on the ground with respect to programs and strategies; these are changes being talked about, but they are mostly just talk for now,” Montemayor said.

“It does need some time to ramp up all the plans and ‘aspirations,’ but I doubt if the present bureaucracy in the DA will have the capacity and willingness to make drastic changes,” he added.

One of the underlying reasons for this slow progression may be the historically-low disbursement rate for the DA’s budget. According to the World Bank, the agency’s disbursement rate ranged from 75% to 77% in the years of 2019, 2020, and 2021. This meant that although the DA had the budget, it was underspending on crucial programs, like farm-to-market roads.

“Shortcomings of the agencies’ internal processes such as unrealistic cash programs, poor coordination between planning and budget and operations groups, procurement problems, processing of claims for payment, and other administrative issues also contributed to unused funds,” the World Bank said in its 2022 year-end report.

How are farmers faring now?

In a bit of hopeful news, some farmers have benefited from a cropping season of high farmgate prices. SINAG monitored that onion growers managed to sell their crops at P50 to P80 a kilo – a marked improvement compared to the pitiful P15 to P30 per kilo in early 2022. This meant that the good prices that traders and retailers enjoyed had finally trickled down to the level of producers.

Cainglet explained that this was partly due to the work of cooperatives and initiatives from the private sector, some of whom have begun purchasing crops directly from farmers.

It remains to be seen whether this will continue.

But just beyond the horizon, trouble is brewing. The Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) said that based on recent conditions and model forecasts, the El Niño phenomenon is likely to “emerge” between June and August.

An El Niño season can spoil the production of crops due to rising temperatures. In 2019, the DA estimated that production losses due to El Niño reached P7.96 billion. National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) Secretary Arsenio Balisacan previously warned that the agriculture sector could suffer from droughts, saying that a slight El Niño season could cause agricultural production to dip by 1% to 2%.

Facing this looming threat, the DA will need the strongest set of leaders that this country has to offer. – Rappler.com

1 comment

How does this make you feel?

![[ANALYSIS] The department of ambivalent, if not ambiguous agriculture](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/department-of-ambivalent-05252024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=279px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[In This Economy] Marcos Year 2: Missed targets, missing reforms](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-Marcos-Year-2-missed-targets-missing-reforms-July-5-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=134px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[ANALYSIS] The political divorce rocking the Philippines](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-duterte-marcos-china-US-feud-july-4-2024.png?resize=257%2C257&crop=303px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

Firstly, while this article of LANCE SPENCER YU does mention a “Sibuyas Queen”, would there be a “Sibuyas King”? (Reference initials: M.A. and M.M., who is who?) Secondly, how about imagining a probable situation based on the statement of Sen. Hontiveros: “… state-sponsored formation of a cartel”? For example, that “state-sponsored formation of a cartel” did happen even before the present Marcos Jr. Administration, because that state-sponsored formation of a cartel (or perhaps cartels) may even had begun during the time of the Marcos Sr. Administration. These cartels may have just adapted to whoever becomes the President but they could also changed into not only state-sponsored cartels but, worse – STATE-LED cartels!