SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

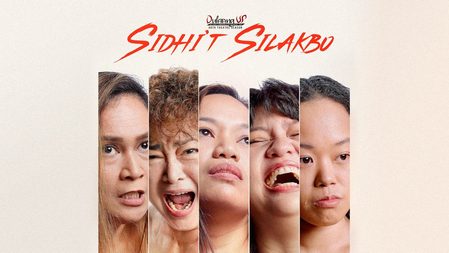

Before Dulaang UP’s Sidhi’t Silakbo begins, a series of silhouettes are projected across strips of thin white fabric, the montage punctuated only by a series of quotes from history’s most hated women. First from Genesis regarding Eve’s creation and the original sin, then later a reference questioning Medusa’s monstrosity. These first few moments establish the feminine construct that directors Issa Manalo Lopez and Tess Jamias are pushing against — one that imagines women as sinful, silent, and complicit in preserving the same systems that oppress them.

Sidhi’t Silakbo can be seen as an attempt to create a collective biography of Filipino women through theater, much like how Paul Preciado’s recent work Orlando: My Political Biography uses Virginia Woolf’s 1928 Orlando: A Biography as a template to articulate the plurality of the trans and non-binary experience. The first vignette draws from Charles L. Mee’s Big Love, an adaptation of Aeschylus’ The Suppliants, and finds all five women, at first nameless, entering the thrust stage in black undergarments. Slowly, they take clothes splayed across the floor and put them on as they deliver their monologues, almost as if testing the archetypes to see if they’d fit. They talk about the men in their lives — the ones who woo them and use them, often in the same breath.

The whole affair is reminiscent of Eve Ensler’s Vagina Monologues and even this year’s travesty Phil Noble’s DickTalk. But whereas DickTalk situates itself in the contemporary assertions of manhood, playwright Maynard Manansala and the ensemble attempt to bridge the past and the present by anchoring its stories on Greek tragedies, showing how contemporary issues have an unerasable cyclicality to them that can be traced back to these early accidental feminist icons. Helen Foley’s Female Acts in Greek Tragedy put it best: “Tragedy thus exploits, reinforces, and questions cultural clichés about women and gender in a fashion that resonates with contemporary Athenian social and political issues.”

In the second vignette Antigone and Ismene, the two siblings (Uzziel Delamide and Wenah Nagales, respectively) argue loudly in the night after Antigone buries their brother’s body, harkening to Oplan Sauron in Negros Island. Behind them, a forest has been reduced to cinders. Silhouettes of soldiers slowly replace burnt tree stumps, becoming scarecrows for the living through Jana Jimenez’s haunting video design. They build in number as the two argue, tugging between following rules and breaking them. Delamide and Negales’ performance throws much of its energy away in the first few minutes and remains at this exhausting high until the two are forced into silence by a knock on the door. Darkness soon follows.

This resistance to the daintiness and quiet of the “ideal” Filipina powers the performances of Sidhi’t Silakbo and each actor pushes against subtlety and uses a maximalism, a bravura, that does not always match the needs of the material. In the third vignette, Medea (Chic San Agustin-De Guzman) discovers that her husband is cheating on her and, in a fit of passive aggression and pettiness, goes on Facebook Live to expose him to her followers. Once she has gotten her momentary retribution and the pleasantries dissolve, her private breakdown is explosive, messy, and borderline placeless. In the fourth vignette, Medea (now played by Adrienne Vergara), whose flight has now been delayed by a freak storm, furiously vacillates between killing her children now or leaving them with their irresponsible father to die later, eventually abandoning her destination to follow through with filicide.

These embodiments of feminine rage have taken centerstage and are part of an international movement in art toward articulating what was once taboo and “unlikeable” about “unacceptable” women. Sabrina Basilio’s Antigone vs. the People of the Philippines is a devised theater piece that transplants Antigone to the Philippines and presents her complexities through multiple lenses of an increasingly public trial. Similarly, Alice Diop’s Saint Omer adapts the story of Medea into a French courtroom drama. As in the words of film critic Richard Brody, “using the power language to spark imagination,” Diop exhumes the injustices against Black female bodies and African traditions. Yorgos Lanthimos’ Poor Things similarly draws from Medea’s connection to Frankenstein’s monster and parallels worldly discoveries with sexual liberation, often embarrassing and cuckolding the men in her way, revealing their state as pathetic sexual pawns and losers in the game of life.

In the souvenir program, Sidhi’t Silakbo’s artistic and technical team makes it clear that they seek to critique the male gaze (as defined by film theorist Laura Mulvey), hoping to arrive at play where the women have “an identity that is apart from how the male sees them.” Yet its female characters’ existences are in constant reference to the men in their lives, remaining subjugated by forces that remain offstage, who despite their physical absence power the narrative’s momentum. The material’s insistence on this dystopic reality — one still similar to the patriarchal present of the Philippines — fails to align with its desire to critique and transgress the status quo, and so Sidhi’t Silakbo’s feminism registers as incomplete. In principle, it condemns the ways women suffer. But in actuality, it still cannot avoid depicting the ways women are emaciated, brutalized, harassed, and killed.

This peaks in the fifth vignette: when a female Creon (Negales) fails to toy with a worn-down but continuously petulant Antigone (Delamide), the scene suddenly pivots into Antigone’s murder. Many details of the scene make the power imbalance difficult to believe, particularly the shiftiness and animatedness with which Nagales embodies Creon, her authority over both Antigone and the scene slipping off as easily as her clothing. Up until this point, the dominator had been an invisible force, existing purposefully offstage or as a silhouette on video projections in an attempt to center the narrative on the women. But by giving form to death itself, the play’s overall power decreases, limiting imagined forms patriarchy can terrifyingly take on.

Even the production’s sixth vignette – which features not only a powerhouse performance by Shamaine Buencamino as the withered Andromache but also its most provocative sequences, weaving the threat of nuclear warfare with slavery and sexual experimentation – struggles to find emotional footing. Sidhi’t Silakbo struggles to be equally radical with its images, narrative, and political positioning. It is not a refusal of mastery nor a celebration of marginality, often more occupied with identity rather than aesthetic analysis. It makes attempts at these but reveals little of the interiority of the women beyond what they represent, all efforts at empathy rendered unfairly asymptotic.

The first six vignettes have all of the women describing the gendered cages that constrict them — war, marriage, motherhood, filicide, the justice system, sexuality, class, and slavery. But rather than finding ways out of these socially constructed prisons, it has then rushing towards the door, only to stop short of escape. Sidhi’t Silakbo wants to divorce its women from the political reality of subjugation, but it can only imagine women within these binaries that categorize them into either victims or oppressors. Even as the play progresses, it is unclear what third political reality Lopez and Jamias want the women to move towards, and, in struggling to imagine a world where dominators do not exist, the destination of the piece remains elusive.

Only in the final moments of the play, when the women focus on sleeping, anime, play, and other mundane joys does the material find any new territory worth exploring. As the five women transform a simple cloth into a parachute or a hug, functioning not as individuals but as a communal unit, Lopez and Jamias give body, choreography, and form to this joy and create a contrast to the loneliness and rage women are left to deal with in solitude. The ease with which these are delivered and the sense of delight in the play exposes how reliance on Greek tragedy as a backbone has become an artistic crutch, inadvertently exchanging cultural and personal specificities for the general appeal of universality and timelessness, restricting the production when its form and content aspire for liberation.

This final vignette is when Sidhi’t Silakbo approaches its radical potential the most. It invites us into a female utopia wherein women are not subjugated even by stories or storytelling methods. It is not an outright ignorance of women’s struggles, but rather a reminder that suffering is not the only thing that persists. While even this ending is neutered by a series of references to successful women — many of whom are not fully emancipated due to dominator culture — it affirms the potential of the devising process as a disruptor of the status quo. Given Dulaang UP’s admirable commitment to process and desire to continue devising this text and other texts, one hopes that they only become fuller collective political biographies, clearer with what they aspire to reflect back to the audience. – Rappler.com

‘Sidhi’t Silakbo‘ is Dulaang UP’s first attempt at mounting not only a production but an entire season dedicated to and led by women. It was staged at the new IBG-KAL Theater, University of the Philippines Diliman from November 23-December 3, 2023.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.