SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

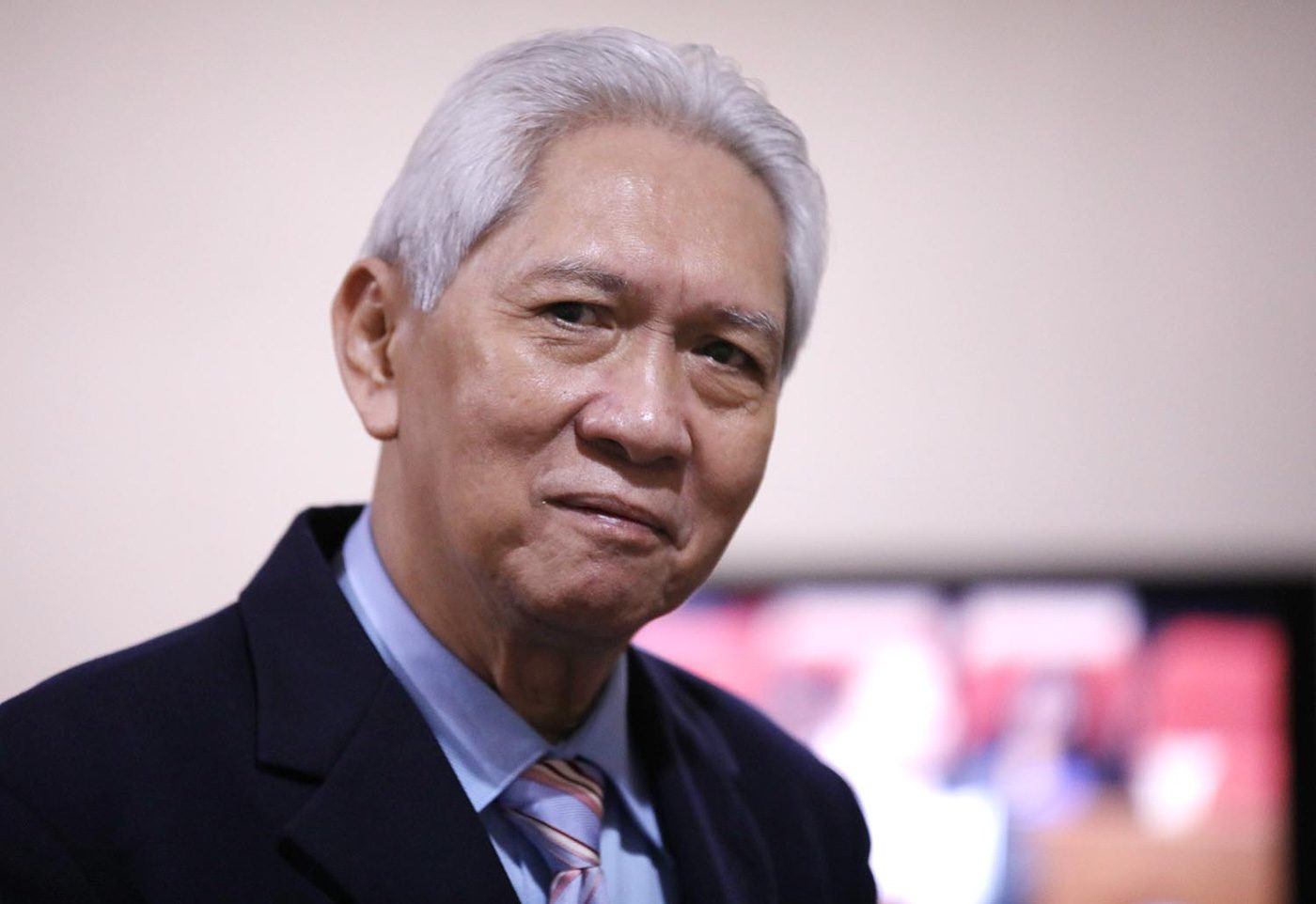

Ombudsman Samuel Martires has implemented a string of policies that protect public officials, moving to stop lifestyle checks and adopting a system that will have a less criminal treatment of corruption cases.

Martires revealed these details on Tuesday, September 22, as he appealed to the House of Representatives to restore his office’s 2021 budget to the originally proposed of P4.6 billion. The Department of Budget and Management (DBM) cut it down to only P3.36 billion.

One of the affected item in the budget cut was Personnel Services (PS), which Martires said would derail his plan of putting up a separate bureau that would solely handle the administrative aspects of a corruption case.

This is the latest in a series of reforms in the Office of the Ombudsman that favors public officials.

Martires earlier imposed a rule where the Office of the Ombudsman will no longer elevate a case to the Supreme Court once it loses at the lower courts. He has also recalled sanctions against officials who violated the Solid Waste Act, saying it was not economically feasible to implement public officials’ obligations under the law.

Recently, he restricted public access to Statements of Assets, Liabilities and Net Worth (SALN), saying SALNs had been weaponized.

Less criminal treatment

Martires said he wanted to separate the investigation of criminal and administrative aspects of one case, the goal of which is to have a less criminal treatment of cases.

In the Office of the Ombudsman, the same team of prosecutors decide the criminal and administrative liabilities of a person. Sometimes, the administrative aspects are decided first, and officials found guilty are either suspended or dismissed.

The criminal aspect follows, which, in the finding of a probable cause, results in the filing of a criminal charge before the anti-graft court Sandiganbayan.

“I want to designate a separate person to resolve the administrative aspect of a case, so if in the administrative aspect they see no liability, they now have to reconcile. Will you still pursue a criminal case if there is no longer an administrative liability?” Martires said in Filipino.

Martires, a former justice of the anti-graft court Sandiganbayan, said there were far too many public officials being prosecuted criminally for small cases, such as for failure to liquidate.

“To my mind this is a form of harassment against a government official,” Martires told lawmakers.

The Ombudsman said public officials who missed deadlines for liquidating their expenses often got around to accomplishing the tasks anyway, but by then the Ombudsman said an audit report had already been used by the officials’ political foes.

“Is our law so harsh that a person gets jailed or penalized even for a small mistake?” he said.

The Ombudsman’s idea might be good, said law professor and former Ateneo School of Government dean Tony La Viña, “mainly because having too many criminal cases guarantee failure in prosecution.”

There has also been constant criticism that the low-ranking officials – who may have been used as fall guys or whose lapses involve small amounts of money – are the ones easily prosecuted because they lack access to competent defense.

“Only directors and above should be prosecuted for financial graft and corruption and for a certain minimum amount. Officials lower than director can be prosecuted if they are accomplices,” said La Viña.

The Ombudsman law mandates that priority shall be given to “complaints filed against high ranking government officials and/or those occupying supervisory positions, complaints involving grave offenses as well as complaints involving large sums of money and/or properties.” (READ: ‘Parking’ fee? Fault lies in Ombudsman setup)

No more lifestyle checks

In the course of questioning, Martires also revealed that the Office of the Ombudsman had not done any lifestyle check since he was appointed by President Rodrigo Duterte in July 2018.

“I put a stop to lifestyle checks because I have had questions and doubts about the provisions on lifestyle checks,” he said.

“I was about to propose to Congress to amend [Republic Act] 6713. There are really provisions there that are either confusing or just simply illogical,” said Martires.

RA 6713 prohibits officials from receiving gifts, engaging in transactions which have conflict of interest, and even requiring that they live simple lives.

“Public officials and employees and their families shall lead modest lives appropriate to their positions and income. They shall not indulge in extravagant or ostentatious display of wealth in any form,” says Section 4(h) of the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees.

As Martires put it, if an official handles his money well and is able to buy an expensive car, “Why should we meddle in their lives?”

Lifestyle checks are prompted when there are indications that the official’s lifestyle seems to be beyond his income.

“What is simple living to me may not be simple living to anyone of you. Probably he must have distorted values, but why do we care, who are we to judge the person?” the Ombudsman said.

Martires said many officials had fallen “victims” to the law.

‘Abolish the Office of the Ombudsman’

At one point, Martires expressed frustration that while many speculated about corruption in government, only few were willing to testify.

“The reason we can’t catch anybody is because the complainants themselves are scared. Nothing will happen if they’re like that. I’ve said this: Maybe we should just abolish the Office of the Ombudsman,” said Martires.

As special prosecutor, the Office of the Ombudsman has a more proactive role than the ordinary prosecutors of the Department of Justice. It has its own fact-finding department, where investigators can actively search for evidence.

The Office of the Ombudsman also need not wait for a complaint, as it has the power under its charter to launch investigations motu proprio or on its own initiative.

Asked about the efforts to recover the ill-gotten wealth of the Marcoses, Martires simply said that, in the two years he had not met anyone from the Presidential Commission on Good Government or the agency created specifically to investigate the Marcos wealth.

“That’s tragic,” was all that Bayan Muna Representative Carlos Zarate could say. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.