SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

AT A GLANCE

- The Philippines is poorly equipped to fight cybercrime and cyberattacks

- Israel, second only to the United States in cybersecurity, proves how a small country can succesfully protect its citizens

- The Philippines has a lot to learn from Israel and must act quickly to secure critical “infostructure”, government and military networks, business and supply chains, and individuals and internet users

TEL AVIV, Israel – Daniel Perry was 17 years old when he took his own life.

Perry had been speaking to a young and pretty American girl his age on Skype. After Perry swapped intimate photos and engaged in an explicit video chat with his online friend, blackmailers revealed themselves and told him their intimate interactions and conversations had been recorded.

They threatened to share the recording with Perry’s friends and family, unless he paid up. There was no girl.

Feeling humiliated, trapped, and with no money, the Scottish teenager jumped off a bridge on July 15, 2013, the victim of an online sextortion scam.

About 10 months later, some 10,500 kilometers away in the Philippines, members of the Philippine National Police Anti-Cybercrime Group, along with Interpol, raided premises across the country in Bicol, Bulacan, Laguna, and Taguig City.

Operation Strikeback resulted in 58 arrested individuals, and the seizure of 250 pieces of electronics.

Investigations from earlier months revealed that Perry was a victim of an organized crime group operating out of the Philippines.

The criminal network, focused on sextortion – or sexual blackmail in which sexual information or images are used to extort money from the victim – lured victims from Hong Kong, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The criminal group duped them into engaging in cybersex, then asked for blackmail amounts ranging from $500 to $15,000.

At that time, Interpol praised the cooperation from various countries involved in cracking the crime – especially the work of Philippine police.

“The success of Operation Strikeback is down to the cooperation between the law enforcement agencies in the involved countries, particularly the Philippine National Police (PNP),” said Noboru Nakatani, executive director of the Interpol Global Complex for Innovation.

Today, PNP Anti-Cybercrime Group (PNP-ACG)’s Chief of Investigation Section, Senior Inspector Artemio Jun Cinco Jr, still regards Operation Strikeback as the unit’s biggest achievement.

“The cybercrime group was the one responsible for pinning down the syndicates,” he said. “We were recognized internationally for that case.”

But that was 2014. Fast forward to 4 years, what is the status of the PNP-ACG today?

Philippine capabilities

The PNP-ACG is responsible for fighting “whatever type of crime as long as it was done using cyber or technology,” Cinco told Rappler on Tuesday, February 6.

The definition encompasses a vast spectrum of crimes, but in PNP-ACG’s latest statistics released January 2017, the top complaint received by the unit were online libel, comprising 26.49% of the 1,865 cybercrime complaints for 2016.

Online scam complaints came in second place, with 444 complaints in 2016, followed by identity theft, online threats, and violation of the anti-photo and video voyeurism act, which includes revenge porn and sextortion.

The number of overall complaints has risen year on year, since the PNP-ACG was activated as a National Operational Support Unit in 2013.

“We get a minimum of 10 complaints a day in Manila alone, at the headquarters,” said Cinco. “That doesn’t include complaints from offices in 11 other regions.”

In addition, he estimated about 2-3 requests for cooperation from other international agencies daily.

Cinco said cybercrime investigators of the PNP work hard to keep up not just with the frequency of crimes, but also with thei ever evolving nature. Because of technology that continues to change rapidly, it is crucial for the team to get constant training in order not to get left behind.

In the PNP, there are 4 mandatory training courses to become a cybercrime investigator – on top of the required cop training at the PNP Academy. Training courses include proactive internet investigation, cybercrime investigation, forensic digital examination, and basic computer knowledge.

In order for the unit to be updated, Cinco said “all members of the cybercrime group have a continuous program of learning” through training and consultations abroad, in partnership with other countries and international law enforcement agencies.

As a member of Interpol, the PNP-ACG members are trained by counterparts from Japan, Korea, China, and the European Union.

Cinco said annually, the unit’s members engage in up to 35 training opportunities abroad. At the time of this interview, PNP-ACG Director Marni Marcos was in Japan for training along with his Chief of Staff.

Cinco said that while everyone in the unit is “not necessarily a graduate of a computer course,” the mandatory courses “will definitely equip you” to fight cybercrime. Only those in the forensic section of PNP-ACG are required to be computer course graduates, since it is this section that’s in charge of collecting digital evidence and performing autopsies on computers, cell phones, and other equipment.

The unit also seeks help from an advisory council, composed of private individuals, stakeholders, and members of companies involved in IT.

Cinco expressed confidence in the ability of the unit.

“During our training abroad with regional law enforcement agencies, in my own assessment, we are more capable than them in equipment and skill,” he said.

Left behind

His assessment is not entirely accurate.

According to Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT) assistant secretary for Cybersecurity and Enabling Technologies Allan S. Cabanlong, the Philippines is only in the Reactive and Manual phase and the Tools-based phase of cybersecurity, based on the Cybersecurity Maturity Model of the US Department of Defense.

This means the Philippines is still focused on eliminating cyber threats as they happen, rather than finding their causes and preventing them from happening. This means it only provides tools to individuals to allow them to react faster to threats.

Cabanlong also said that the Philippines has a significant lack of local cybersecurity experts, compared to its Southeast Asian neighbors. The Philippines only has 84 certified information security systems professionals – half of whom work overseas. This number is lower compared to Indonesia’s 107, Thailand’s 189, Malaysia’s 275, and Singapore’s 1,000.

The lack of the country’s prioritization of cybersecurity is also evident in the small investment in it.

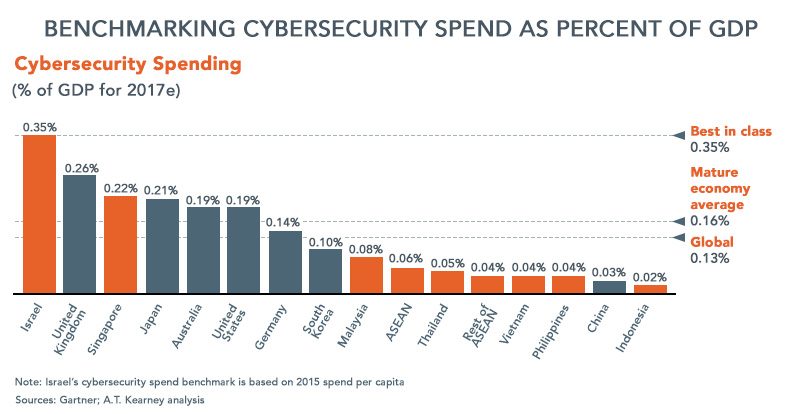

According to an ASEAN cybersecurity report released in 2017 by global management consulting firm AT Kearney, the Philippines spent just 0.04% of its gross domestic product to cybersecurity. This is below ASEAN’s cybersecurity spend, which was 0.06% of the region’s GDP.

The Philippines was also behind Singapore’s 0.22%, Malaysia’s 0.08%, and Thailand’s 0.05%.

On the very top of the global spectrum is Israel – which spends 0.35% of its GDP on cybersecurity. It’s the highest in the world, and the best in class.

Israel’s cyberunit

Yaniv Azani, the Chief Technology Officer of the Israel Police’s cyber unit (Lahav433), looks young – much like what one would expect a CTO of a tech company to look like.

But like many techies in Israel who dive into the workforce as soon as they can, his career spans over 20 years – with a variety of assignments in the technological division of the Israel Defense Force, the Israeli Ministry of Defense, and the Israeli National Police.

Here in Tel Aviv, the youth breathe tech: kindergarten kids in some schools learn computer skills and robotics, talented 10th-graders learn to code and stop hacking, and university students dream of launching their own startup. Israel is home to the likes of traffic navigation app Waze, and the pioneering messaging app ICQ.

For a country that is just 60 years old and with a population of just 7.1 million, Israel boasts of having the most NASDAQ-listed companies outside America. It also has more high tech startups per capita in the entire world, at 5,500.

At the prominent Cybertech conference alone, 90 local startups showed off latest technologies in cybersecurity, vowing to protect companies around the world from the most advanced and sophisticated attacks.

Lahav433, established 4 years ago, deals with anything related to cybercrime and its investigation.

The crimes Lahav433 deals with are significantly more sophisticated than those of the Philippine police: they’re everything from money laundering, to corruption, to organized crime. They also work closely with the military on parallel investigations when it comes to terror probes that turn criminal.

“We are responsible for two types of crimes. Pure cybercrimes like hacking and espionage, and cyber-enabled crimes like selling drugs in the dark net,” he said. “It’s not pure cybercrime but it’s still under our responsibility.”

The PNP-ACG has a lot to learn from Lahav433.

Israel, surrounded by enemies and in the middle of conflict since its inception, has learned over time to protect itself in innovative ways. Lahav433 said it receives up to 40 reports per day, significantly more than the PNP’s, despite Israel being much smaller than the Philippines.

Azani acknowledged that like the PNP, one of their main challenges is training, because everything is “still developing so fast and so rapidly, there’s new technology all the time.”

But unlike the PNP, he said they count on 3 different levels of training: actual, internal, and on-the-job training.

Actual training is adopting best practices from outside the unit, and from top experts. “We’re not trying to compete with others,” said Azani. “We value outsourced information.”

The second, like the PNP, is police academy training, and using their own internal information to strengthen the unit.

But Lahav433 also highly values on-the-job training.

“We hire new people without training or knowledge and almost zero knowledge on missions,” said Azani.

While the PNP-ACG requires all unit members to undergo police academy training, this does not hold true for Lahav433.

“Academic training is good but there is no replacement for the creativity of a specific person,” he said. “People without experience can be trained and run away with it.”

Among their staff are 19-year-old women with zero security experience, but who have become valuable assets to the team.

Valuing the youth and their digital know-how also shows in Lahav433’s unit composition.

“It’s very valuable for us to have young people on our team. It’s a new generation. They were born into the technology. Their mind is wired differently,” said Yaniv.

“They have the ability to adapt to changes, to learn faster, to be more creative. It’s impossible to succeed without young people.”

In contrast, the PNP-ACG can only recruit individuals who went through at least one year of police training, and must be 21 years old and above. It has the same composition as other police units, and the same quota for new recruits, despite the unit possibly requiring a younger demographic.

Because of studies that say peak creativity is around 30 years old, Yaniv said they’ve opened their doors to the youth.

“They want to bring in the change. Experience is good but the creativity the youth give is better. The creativity is what changes the game.”

Cybersecurity powerhouse

Lahav433 is also at an advantage in that the unit is able to tap some of the best cybersecurity experts in the world – because many of them are Israeli.

Israel is a cybersecurity powerhouse at the center of an $82-billion industry. It received 20% of the global private cybersecurity investment in 2016.

There are various factors that have contributed to Israel’s rise in cybersecurity – like culture and mandatory military service – but one major driver is the government and its role in not just encouraging startups, but also financing them.

The Israel Innovation Authority for instance, is a government arm under the Ministry of Economy, that is responsible for encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship while stimulating economic growth.

Former Apple Israel chief and now head of the Innovation Authority Aharon Aharon, said the government spends 4% of its GDP on supporting startups.

“We invested about $500 million in 2017 on innovation and supporting companies. We have a professional evaluator to check out cyber companies applying for government funding,” he said,

“We invest in mobile, cyber, robotics, food tech, bug data, electronics, machine learning and more. We fund all technologies and at all stages of innovation, from startups to large companies.”

There are also the likes of Cybergym – half-owned by the Israeli government’s Israel Electric Company – a cyberdefense organization that trains companies and even governments around the world on how to protect themselves from cyber attacks.

Cybergym CEO and co-founder Ofir Hason said it counts the governments of Lithuania and Australia as some of its clients, and has managed training in Portugal, New York, Australia, and Japan, among others.

“The goal is to share this knowledge worldwide with the good guys,” he said.

But from the Philippines, he said it has only been banks so far that have sought their help.

Efforts to improve

There is some effort from the Philippines to improve its cybersecurity capabilities, including support for law enforcement agencies like the PNP.

Ranked the 46th most targeted country globally, according to Kaspersky Lab’s Industrial CyberThreats Real Time Map, the Philippine government knows there is a need to step up its cyberdefenses. In 2016, at least 68 government websites were attacked after the United Nations International arbitration court ruled in favor of the Philippines on the West Philippine Sea territorial dispute.

In 2017, the government launched its National Cybersecurity Plan 2022. It aims to protect critical infostructure (CII), government and military networks, business and supply chains, and individuals and internet users. It is responsible for assessing cybersecurity capabilities of various sectors and coordinating efforts with departments and law enforcement agencies.

The DICT, the government agency tasked with leading the plan, also aims to integrate cybersecurity into the academic curriculum of high school, college, and graduate students.

The road to securing the Philippines is tough. The AT Kearney study found that the Philippines should invest $8.8 billion in cybersecurity from now till 2025, to reach the average benchmark for mature markets like the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany.

For now, Cinco said this is the real struggle for the PNP-ACG: money.

“Funding is short because equipment is expensive. It’s worth millions. You need to upgrade from time to time, you can’t even wait a year. Because the system of the enemy improves all the time, we need money,” he said.

“Crime is always evolving, every day there is something new. If they have a new technique, we also have to have a new response.”

He also said that while the unit is capable when it comes to the “same traditional offenses that are brought online,” it is the deeply technical cybercrimes that are difficult to solve.

“Normally if you see our stats, extortion cases, the application of traditional way of investigation involving cybercrime are easy to solve. When it comes to highly technical things, like warfare online, it’s another issue,” he said.

“We should be more proactive when it comes to cybersecurity, not reactive,” he admitted.

Aside from this, Cinco said it is a challenge for the PNP-ACG to investigate and pursue criminals, because of limited cooperation from other agencies – both government and private – like internet service providers.

The Cybersecurity Plan, while delayed, is at least something to look forward to, for those tasked to protect the Philippines from cyberattacks.

About 4 years since Operation Strikeback – which is more than enough time for hackers and cybercriminals to evolve – the PNP-ACG is beyond its glory days in cybercrime protection.

It’s crucial for the Philippine government to emulate capabilities of states like Israel, before it’s too late. – Rappler.com

Natashya Gutierrez traveled to Tel Aviv, Israel as part of a journalist delegation supported by the Israel Foreign Ministry.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.