SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – On February 12, 2018, Joanna Demafelis returned to the Philippines in a wooden crate, welcomed by grieving family members who still couldn’t believe that she had been dead for nearly two years, her corpse kept in a freezer in an abandoned apartment in Kuwait.

The gruesome discovery of her remains sent shockwaves across the overseas Filipino worker (OFW) community and stoked outrage back home. President Rodrigo Duterte called her death a “national shame” and ordered a ban on the deployment of Filipino workers to Kuwait.

Five years earlier, in January 2013, Joanna had not even thought of leaving the country.

The 26-year-old worked as a housekeeper for her relatives in Parañaque. She had enough money to send home to her parents in Sara, Iloilo, and she had the freedom to stroll around the country’s largest malls.

But in late 2013, a powerful storm that swept across Eastern Visayas altered her plans. Super Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) left over 6,000 people dead, and P4.55-billion worth of infrastructure lost.

Among those who suddenly found themselves homeless in the aftermath of Yolanda was the Demafelis family. The raging floods stripped down the family home to its frame, and felled the old avocado tree that gave shade to the 9 Demafelis siblings when they were younger.

The rice and sugarcane fields that farmer-parents tilled became pits filled with trash and debris, while their town center had ruptured roads and broken buildings.

“Napakahirap na panahon na iyon sa aming pamilya (It was a very difficult time for our family),” Joejet Demafelis, Joanna’s older brother, told Rappler in a phone interview.

Joejet explained that her parents only leased the farmland. Since the storm destroyed their crops and the land could not be tilled, they had no other source of income. Their debts quickly piled up.

From Sara town a month after the typhoon, Joanna made a decision that ultimately sent her on her ill-fated journey to Kuwait. She sent a chat message to a distant aunt, Agnes Tuballes.

“Tita, puwede mo ba akong tulungan? Gusto ko mag-abroad (Auntie, could you help me? I’d like to go abroad),” Tuballes recalled Joanna telling her the first time they communicated.

A Filipina in Kuwait

In May 2014, 5 months after she talked to her “aunt,” Joanna finally hopped on a plane headed to Kuwait. The Arab country is only the size of the Philippines’ Zamboanga Peninsula, but had enough oil reserves to make it the 4th richest country in the world per capita, second only in the Gulf region to Qatar.

As demand rose for househelp in Kuwait, many Filipinas flocked to the country. Tales of abuse followed. Filipinas fell to their deaths from apartment buildings, for reasons still unknown. A domestic helper died after an illegally-leashed lion pounced on her.

In Kuwait, Philippine government offices at any given time sheltered hundreds of Filipinas pleading to go home after their daring escape from their abusive employers.

“Embassies report receiving thousands of complaints about confinement [of domestic helpers] in the house, months or years of unpaid wages, long work hours without rest, and verbal, physical, and sexual abuse,” Human Rights Watch said of the plight of migrant domestic workers in Kuwait in its 2013 report.

Joejet said the risk involved discouraged Joanna, but there were other things she found far more frightening: a house forever half-built and unpainted, a family dining table always empty, her parents laboring in farmlands for the rest of their days, her youngest sibling robbed of education, and another sister taking the risk for the family instead.

Joanna overcame her fears and got her parents’ blessing to work in Kuwait.

Kuwait provided the job she could never have in Sara, working as a domestic helper with a minimum monthly salary of $400 – around 10 times her salary as a helper in her homeland.

Rules in the promised land

The high wage came at a high price. Kuwait, like other Arab countries, uses the Kafala sponsorship system – an archaic arrangement for foreigners seeking work in the expatriate-dominated country.

Under the system, migrant workers like OFWs cannot enter the country to work just on their own qualifications. They need to look for a sponsor who will act as their bridge to the country.

Sponsors can be multimillion-dollar companies or simply Kuwaiti families looking for housekeepers. OFW deployment to Kuwait is mostly hinged on the latter.

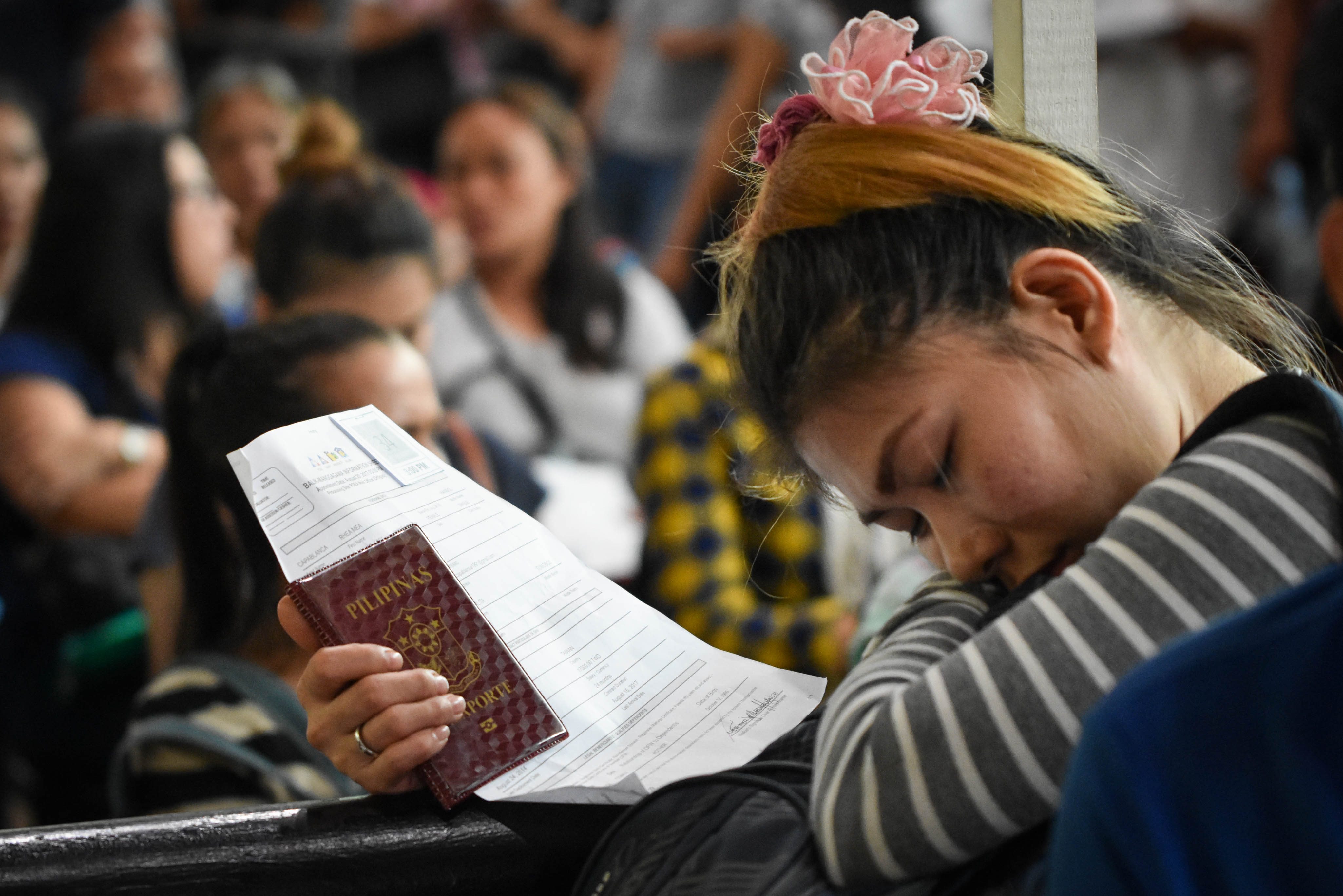

According to data from the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA), over 240,000 Filipino workers are deployed in Kuwait for work, around 165,000 of whom are mostly female domestic helpers.

In the case of domestic helpers, Kuwait requires a “domestic servant visa” usually processed by a recruitment agency.

The employer gets to keep the worker’s passport. The worker can’t change jobs without the approval of her employers. If the employer fires his worker, the worker would have to look for another sponsor or she would be deported. If the worker escapes from employment, she can be penalized.

On top of the strict laws governing domestic helpers, the laws that protect them from violence “haven’t been effective,” according to a Kuwaiti Times article written by Sana Kalim.

“In Kuwaiti culture, problems of spousal abuse are often dealt with within the family, which is the core institution of the society. Kuwaiti families often consider it an embarrassment if they cannot successfully address such problems without outside involvement,” says the country briefer of the United States embassy in Kuwait.

“These attitudes are reflected in Kuwaiti law, which considers an assault against another person to be a misdemeanor, rather than a felony, unless a weapon was used,” it added.

Joanna also had to abide by her employers’ house rules. Her cellphone was apparently confiscated and she was allowed access only every 3 months.

These were the rules Joanna had to live with when she was recruited to work in the country’s Al Shaab region. Presidential Adviser on OFWs Abdullah Mama-o went as far as saying that these rules paved the way for Joanna’s death.

“We may have all the best laws in this country to protect the interest of our domestic workers working in different countries in the world, but if we still have this Kafala system in different parts of the Middle East, we will not have that kind of protection for our workers,” Mama-o said during a Senate probe into OFW deaths.

“This Kafala system should be out because no matter how we protect our domestic helpers…our domestic helpers will still be locked in the room, they cannot go out, they cannot make any contact with the outside world, they cannot send letters, they cannot call. That can be done by the employer, and this happened to the case of Demafelis,” he added.

Trouble in the homeland

For OFW rights group Migrante International, however, there is no need to look far to find and correct the policies that aided Joanna’s death.

According to Migrante International spokesperson Arman Hernando, abused domestic helpers first confide in their families back home.

“When [domestic helpers] are alone there, the persons they really confide information about their experiences first are their relatives,” Hernando told Rappler in a phone interview.

The Demafelis family knew there was a problem in September 2016, when they couldn’t find two of Joanna’s Facebook profiles after a call. They tried to reach her roaming number, but she didn’t answer. That September 2016 call was the last time any of them heard her voice.

Unable to sleep out of anxiety, the Demafelis family turned to the government, particularly to the Overseas Workers Welfare Administration (OWWA) and the POEA for help.

The two state agencies failed to find Joanna as her recruitment agency, Our Lady of Mt Carmel Global E-Human Resources Incorporated, had already closed.

Kuwaiti authorities found Joanna by chance almost two years later. They went to her employers’ apartment because of unpaid business dues, and made the shocking discovery when they opened the freezer in the abandoned home.

Hernando said the Philippine government failed to find Joanna because the government had too much confidence in recruiters and employers.

“Ipinapasa nila ‘yung obligasyon na i-settle at ayusin ‘yung problema ng mga OFW sa mga recruitment agencies katulad ng nangyari kay Joanna (They pass the obligation of settling OFW problems to recruitment agencies, just like what happned with Joanna),” he said.

He was referring to Republic Act No. 8042 or the Migrant Workers Act. Section 29 of the law states that “the migration of workers becomes strictly a matter between the worker and his foreign employer.”

“Ang gusto sana natin hindi na idaan sa recruitment agency at sa employer, kundi diretso nang tinitingnan ng gobyerno ang kalagayan ng mga OFW, lalo na sa mga bansa tulad ng Kuwait,” Hernando added.

(What we want is that the government would not have to go through the recruitment agency or employer, but instead go straight to the OFWs to see how they are, especially in countries like Kuwait.)

Justice for Joanna

Joanna may have also been a victim of illegal recruitment, a business compatible with a country of an estimated 10 million OFWs.

With Joanna pleading to be sent abroad in 2013, Tuballes referred her to Our Lady of Mt Carmel Global E-Human Resources Incorporated. It was not a simple friendly referral – in endorsing Joanna, Tuballes earned P13,000 from a certain Ara Midtimbang who was looking for OFWs to work in Kuwait.

Midtimbang promised P5,000 for each referral, Tuballes said. It is unclear why she was paid more than double in the case of Joanna.

At Mt Carmel, Demafelis met the agency’s assistant general manager, Mary Gay Canlas Abrantes, and secretary Marissa Ansaji Mohammad, who apparently fixed her deployment papers.

According to the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI), Joanna was handled by the Fadilah Farz Kaued Khodor Recruitment Office while she was in Kuwait.

The two employers who owned the apartment where Joanna was found dead were already her second employers, the NBI said. It is unclear who Joanna’s first employer was, why she left, and how she was able to find Lebanese Nader Essam Assa and his Syrian wife, Mona Hassoun, the suspects in her murder.

Abrantes, Mohammad, and Tuballes are now with the NBI, while Assa and Hassoun had been arrested in Lebanon.

Following Joanna’s death, the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) set up a command center for OFW abuse cases and sent a rapid response team to monitor abuses in the Gulf countries.

Joanna’s death prompted the governments of the Philippines and Kuwait to agree to fast-track a bilateral agreement that promises more protection for tens of thousands of OFWs in Kuwait.

On Saturday, March 3, Joanna was laid to rest in her hometown. Hundreds attended her funeral mass, including Labor Secretary Silvestre Bello III.

When she was laid to rest, the text on her tombstone read: “For if we live, we live to the Lord, and if we die, we die to the Lord.”

Joanna was finally home. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.