SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

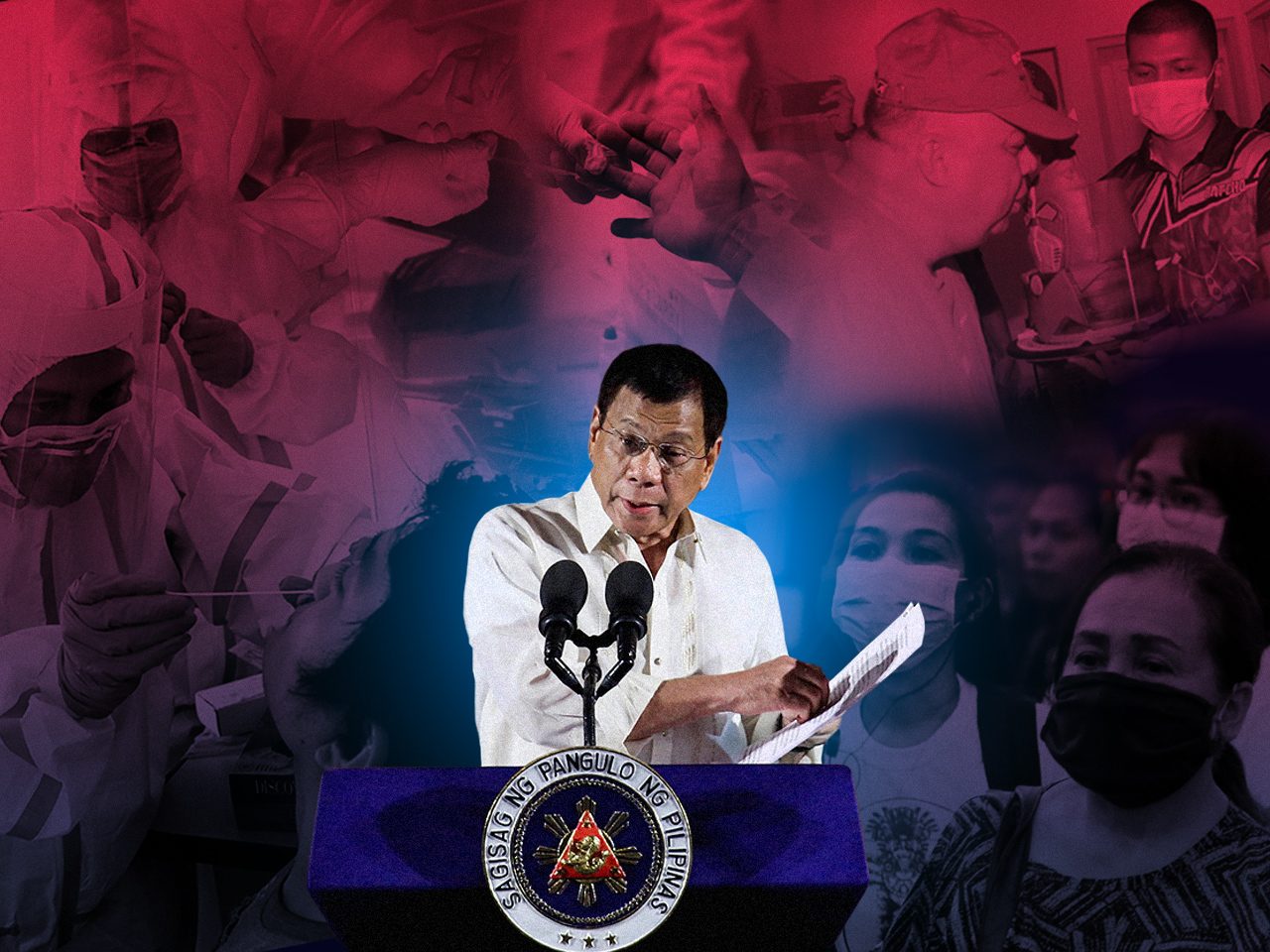

On Monday, July 27, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte addresses a nation brought to its knees by a pandemic.

He also addresses a Congress that just delivered two highly unpopular decisions for him – the rejection of a new franchise for broadcast giant ABS-CBN and the Anti-Terrorism Law his generals pined for.

His State of the Nation Address (SONA) comes after 4 years of steadily amassing power and control, which supporters say is proof of unprecedented political will, and critics fear is a march to authoritarianism.

But with all his power, has he lived up to his promise of a safer and more secure citizenry? As he takes the podium, Filipinos fear a virus infecting more than a thousand each day, the uncertainty of their jobs, and the lack of a clear plan. As if there was not enough fear going around, Duterte certified as urgent, then signed, a dangerously vague law against terrorists that could cover critics of the government.

His allies in the House and his appointee, Solicitor General Jose Calida, moved against well-loved network ABS-CBN, ultimately leading to its shutdown and dark screens for millions of Filipinos dependent on the station for news, information, and entertainment.

But unlike many other controversies he has faced, the signing of the terror bill and maneuverings against ABS-CBN inspired organic and widespread resistance.

Opposition to the terror law reached even the usually silent business groups. Duterte’s allies in Muslim Mindanao, led by Bangsamoro Interim Chief Minister Murad Ebrahim, were among the strongest voices against the measure. Thousands stepped out of their homes during quarantine to hold socially-distanced rallies. “Masked but not silenced,” read one protester’s placard.

For ABS-CBN, a network that has given low-income Filipinos both entertainment and succor for much longer than Duterte has been in power, support was swift and strong. The country’s most influential celebrities rallied for their home network, and journalists from all over the country condemned the shutdown as the greatest blow to press freedom since the Marcos dictatorship. A Social Weather Stations (SWS) survey found that a big majority of Filipinos, 75%, believed Congress should allow ABS-CBN to go back on air.

The blowback has been to such a pitch that Duterte’s own communications team saw it necessary to edit out portions of a recent speech where he appeared to gloat about ABS-CBN’s fate.

A month after ABS-CBN went dark, a Manila court convicted Rappler CEO Maria Ressa and former researcher Reynaldo Santos Jr in a cyber libel case over a 2012 article. Experts and advocates around the world denounced this verdict as an attack on press freedom.

Sustaining popularity amid a pandemic

Duterte’s popularity and the success of his last two years in power are on the line. Already, the lackluster pandemic response may be causing dissatisfaction and fueling anger over other controversies. (READ: Pandemic unravels Duterte’s 2016 promise of decisive leadership)

While there are no local surveys to capture these public frustrations (ironically, because of the lockdowns themselves), an international survey by the London think tank YouGov showed this to be the case.

The survey found that Filipinos who rated the Duterte government’s response as “very” well or “somewhat” well fell from 72% in May to 51% on June 29, a month before the SONA. That’s a 21-point drop in one month.

The pandemic exposed lack of foresight and contradictions in Duterte’s governance. Those who paid the consequences were disadvantaged Filipinos, the very sectors of society who believed in Duterte’s promise of “tapang at malasakit” (courage and compassion).

The tragic embodiment of this failure was Michelle Silvertino, a single mother who died on a Metro Manila footbridge waiting for a bus to take her home to the province. She was among thousands of Filipinos left stranded when the government lifted the lockdown without allowing public transportation to resume.

Three days before his SONA, thousands of Filipinos packed Rizal Sports Complex waiting for a free ride back to their provinces, sleeping slumped against their bags or each other.

Amid dread of the virus, many Filipinos also fear the heavy hand of Duterte’s government. Police brutality in enforcing quarantine rules led to the killing of an ex-soldier who defied stay-at-home orders. The cop who fired his gun faces murder charges. During the lockdown, police arrested a salesman in Butuan City and a public school teacher in Zambales for social media posts deemed threatening or insulting to Duterte.

But what befell Metro Manila police chief Debold Sinas when he allowed his underlings to throw him a surprise birthday celebration that defied health protocols? Defense and praise from no less than Duterte.

No wonder COVID-19 will dominate Duterte’s SONA.

Malacañang has set high expectations. Duterte’s spokesman, Secretary Harry Roque, says the President will finally unveil an economic recovery plan prepared by his economic team.

If this will indeed be the highlight of his Monday speech, Duterte will be sending a message to Congress to go full-throttle on passing economic measures to help businesses get back on their feet, provide jobs to millions of unemployed, and save industries that took the biggest pandemic hit.

Ateneo School of Government Dean Ronald Mendoza, an economist, wants to hear measures to provide direct relief to businesses and workers, rather than stimulus from banks and infrastructure projects assumed to trickle down to Filipinos.

“These trickle-down measures are unlikely to give the urgent and

adequate relief that many small firms and workers need,” he told Rappler.

He also wants to hear about longterm measures to improve the country’s healthcare and social protection systems.

“If these two areas remain weak, then it is unlikely that the country

will manage a robust and inclusive recovery,” said Mendoza, pointing out that Duterte would do well to protect his legacy as the president who signed the 4Ps law (Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program, a conditional cash grant program for poor families) and universal health care law.

But saving the economy will also depend on reining in the virus, something Duterte’s task force has so far failed to do. With the country reporting over a thousand new cases daily for the past week, economies of hubs like Metro Manila, Calabarzon, and Cebu are strapped by quarantine restrictions. So Duterte must also provide a concrete plan on how to stem infections so that more businesses can open up and more people can get back to earning for their families.

Can we expect clarity and focus?

SONAs are traditionally used by presidents to call for unity and support for government. In a crisis like the pandemic, the upcoming SONA becomes a powerful crisis messaging tool that Duterte can wield to inspire confidence and bring the nation together against a challenge that confronts all Filipinos.

But in the past, Duterte’s SONAs have been distracted, disjointed, and unnecessarily hostile to certain sectors of society – notably his critics.

Even his many public addresses on the pandemic had been full of bluster and threats against communists and opposition figures. Filipinos fear that the upcoming SONA will just be more of the same.

In preparation for this, Duterte’s Cabinet continued their tradition of holding “pre-SONA fora,” public conferences where Cabinet secretaries report on accomplishments in strengthening the economy, building infrastructure, helping farmers and entrepreneurs, saving the environment, and protecting citizens against security threats and crime. This year, the fora were virtual, with Cabinet members reporting from their offices and reporters asking their questions through video calls.

“This time, I am much more focused on the pre-SONA which seems quite informative and focused,” said Mendoza, who monitors the SONAs every year.

He called the fora a “useful innovation” that “finally” publicly laid out information necessary to assess the state of the country.

One of the most important pandemic-related presentations was that of Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III, the driving force in the Cabinet for the reopening of the economy amid the pandemic.

Dominguez, whom Duterte recently called “secretary extraordinary,” had practically single-handedly convinced the President and the task force that it was now time to let more businesses operate as long as Filipinos strictly followed rules on mask-wearing and physical distancing.

State of the nation’s pandemic response

“This pandemic is a black swan event that no one fully anticipated and was truly prepared to deal with. But we did not fold and run in the face of an unprecedented crisis. We responded with everything we had,” said Dominguez.

The Duterte government’s biggest move at the start of the crisis was the Metro Manila lockdown and subsequent Luzon quarantine which Dominguez, and all other Cabinet members, say “saved thousands of lives” and bought time to expand testing and boost the healthcare system.

This is true to some extent. From only some 300 tests conducted daily in March, roughly 18,000 tests are now conducted daily, on average, as of end of June. From only 33,000 isolation beds in government facilities in April, this doubled to 68,000 as of early July. From procuring 1 million personal protective equipment (PPE) in April, the government bought 6 million more in June. Dominguez credited the relatively quick procurement and delivery to the special powers Congress gave to Duterte through the Bayanihan to Heal As One Law.

Critics, however, had pointed out that emergency procurement is allowed under other laws so there was no need to approve new powers for the President.

To counter the steady rise of cases depressing Filipinos every day, Dominguez offered some good news: 7.4% test positivity rate. This number means that, out of all tests conducted in the country, only 7.4% come out positive for COVID-19. The World Health Organization says a country should aim to keep their positivity rate below 10%. The Philippines has achieved this, although it’s important to note that the country’s limited testing capability still does not give a complete picture of the virus’ spread.

Currently, the country is yet to reach its May target of 30,000 tests a day. By February or April 2021, the government hopes to have tested 10 million Filipinos, according to testing czar Vince Dizon.

But the lockdowns failed to stop the spread of infections. Realizing the economy could not take a longer lockdown, Duterte and his task force relaxed restrictions and braced for the rise in cases. And rise they did. For each day of the past week, the country’s tally went up by a thousand or 2,000 cases, hard numbers that no amount of spin can erase.

This, while Southeast Asian neighbors like Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia have been reporting single-digit numbers of new infections. The Philippines now has the highest number of active cases (coronavirus patients who have not recovered or died) in Southeast Asia, though it’s second to Indonesia in terms of total confirmed cases.

While Duterte wrongly attributes the spike to supposed widespread violations of health protocols, his task force knows better – it’s because asymptomatic and mild cases had been allowed to stay in homes not suited to self-isolation and because people traveled to their provinces without getting properly tested for the virus.

The latest bid of his government to stop the virus’ spread is to require asymptomatic and mild persons to go to state-run isolation facilities and provide swab testing for persons returning to their hometowns from Metro Manila. But are these efforts too little, too late?

To fund the COVID-19 response, the government has released over P370 billion ($7.49 billion). Most of this, P205 billion ($4.15 billion) – or 1.1% of last year’s gross domestic product – was spent on providing cash assistance to poor families while P51 billion ($1.03 billion) was distributed to displaced workers.

Stick to the issue

The best that Duterte can do during his SONA is to articulate the plan his economic team has crafted and refrain from letting his personal grievances and irritations get in the way.

He should stick to the big picture and save petty fights for later. He should be a president at the helm of a country facing its biggest hurdle instead of a mayor stuck on his beef with a hard-headed company or pesky bureaucrat.

It’s not like he’s never pulled it off. His SONA in 2018 was 50 minutes long and devoid of curse words and lengthy digresses. It was a notable exception to the rest of his SONAs, over an hour long, packed with ad hominem and threats, and where he found time to mention the mice in his presidential palace or his “smelly” girlfriend.

Cabinet members have already laid out some government programs to help bankrupted businesses and even government employees needing laptops. There’s a Social Security Services calamity loan for up to P20,000 ($405). Small businesses can apply for a loan of up to P500,000 ($10,130) from the Department of Trade and Industry to restart their businesses. A million farmers and fishermen have been given P5,000 ($100) by the agriculture department.

The House of Representatives is hammering out a P1.3-trillion ($26.35-billion) recovery stimulus package to get the economy back on its feet but only a loud and clear message from Duterte on the amount needed and the programs to be prioritized will get both chambers of Congress to work.

It’s likely Duterte will mention issues outside of the pandemic. Which these are will be telling because it means they’re of such importance that they remain a priority even amid an expensive health and economic crisis. Definitely, his drug war and fight against terrorists and communists are among them.

But Duterte may find that he no longer calls the shots. Whether he likes it or not, the rest of his presidency will be defined by how he handles the coronavirus crisis. His Monday speech will be his second to the last SONA before Filipinos elect his successor. The failures of his government during the pandemic could provide political fodder for his political rivals in the 2022 presidential elections.

If voters could forgive him for crass remarks, alleged hidden wealth, even his bloody drug war, can they forgive him for losing control of the economy? As past surveys show, Filipinos are typically most concerned about economic issues – like wages, employment, and inflation – more than they are with crime and foreign policy.

Problem is, economy is not Duterte’s strong suit. What Filipinos might expect him to do is listen to Dominguez and the rest of his economic team. His populist contribution may be to ensure the programs provide direct and immediate assistance to workers and businesses, like when he insisted on free college tuition and pension hikes in the face of his economic team’s resistance.

But more than numbers and an alphabet soup of government programs, Filipinos want to hear a plan of action and assurance that, with or without a vaccine, the President will lead the country out of the pandemic’s worst. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] ‘Some people need killing’](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-some-people-need-killing-04172024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.