SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Unanswered questions fill each waking moment of families with missing loved ones – also called desaparecidos – and no amount of time can dissipate the longing that dominates their daily lives.

Their parents, siblings, children, and life partners grasp for answers: What happened? Why were they abducted? Were they killed? Where are they now?

These questions linger in the mind of Victims of Involuntary Disappearances (FIND) co-chairperson Nilda Sevilla, a long-time advocate of concrete and inclusive steps toward justice for desaparecidos and their families.

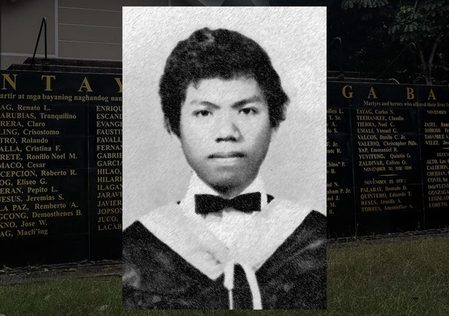

Her brother, Hermon Lagman, was a lawyer who assisted unions and employees subjected to unfair labor practices by their employers. He was also a writer, joining campus publications in high school up until law school, and once served as senior editor of the Philippine Collegian, the main paper of the University of the Philippines, according to Lagman’s profile at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani website.

He became a lawyer in 1971. A year later in 1972, Lagman was one of the first lawyers to be arrested when the dictator Ferdinand Marcos declared Martial Law in the Philippines.

The threat of Marcos’ military rule did not faze Lagman, who continued to help Filipino laborers who bore the brunt of the massive corruption and crony capitalism of Marcos. He assisted for free labor groups that went on strikes and organized pickets, even if there was a blanket ban on group assemblies.

Lagman was again arrested in 1976, but was released a day after. But on May 11, 1977, he and labor activist Victor Reyes disappeared without a trace after leaving for a meeting in Pasay City. Searches conducted in different police and detention facilities yielded nothing.

Lagman was only 32 years old.

It has been 45 years since Lagman disappeared – one of the 640 who remain missing after disappearing during Martial Law – and the pain still feels fresh for the family.

Almost five decades of not knowing the fate of a loved one is cruel, but the family uses this grief to continue calling for justice not just for them, but also for other victims and their families.

The Lagman family, together with nine other families of desaparecidos, went on to establish Families of Victims of Involuntary Disappearances in 1985. The group has since been at the forefront of calls for accountability from the government.

“Naniniwala talaga kami na may karapatan kami sa katotohanan (We really believe that we have the right to the truth),” Sevilla, Lagman’s sister, told Rappler.

“We want to know the truth behind the disappearance of our loved ones and we will assert that,” she continued.

Most comprehensive, but unimplemented

The end of the Marcos dictatorship in 1986 did not end the spate of enforced disappearances in the Philippines. In fact, it has become one of the most recurring forms of state abuse over the years.

FIND documented at least 1,163 victims who remain missing in the Philippines as of June 2022. Out of this number, 523 individuals went missing starting after 1986.

In 2012, then-president Benigno Aquino III signed into law the Anti-Enforced or Involuntary Disappearance Act, which makes the crime of carrying out an enforced disappearance punishable by life imprisonment.

Its principal author was Albay 1st District Representative Edcel Lagman, brother of Martial Law desaparecido Hermon Lagman.

According to the law, an involuntary or enforced disappearance has three elements:

- A person is deprived of liberty via an arrest, detention, or abduction

- The perpetrators are state agents or working with the “authorization, support, or acquiescence” of the state

- There is a conscious effort to conceal the location of the disappeared person

It is one, if not the most, comprehensive law against enforced disappearances in the world and also the first in Asia. What makes it really vital, according to FIND’s Nilda Sevilla, is how it covers all bases.

“It does not only provide for penal, civil, or administrative sanction, it also provides for preventive measures, guaranteeing prosecution and also reparations for victims and families of victims,” she explained to Rappler.

But a decade since its passage, the law remains to be almost unimplemented. Investigations into disappearances hardly progress, with state agents refusing to take accountability over various cases in the past years.

The poor implementation of the law is not just a matter of lack of resources, according to Sevilla.

“There is a lack of political will and human rights protection and promotion is really not their priority,” she said.

Lawmaker Lagman filed a resolution in July 2022 seeking an inquiry into the implementation of the Anti-Enforced or Involuntary Disappearance Act. In a privileged speech on August 30, the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearance, he highlighted the efforts of families of desaparecidos over the 16 years it took to pass the landmark law.

“They and all victims of enforced disappearance under Philippine jurisdiction deserve no less than a faithful and comprehensive enforcement of the law,” he said. “Paying lip service to the measure is an affront to the memory of the disappeared and the struggles of their families for truth and justice.”

The sad state of the landmark law not only frustrates advocates, but ultimately hinders families from seeking justice, especially also in the context of the culture of impunity seen during the administration of former president Rodrigo Duterte.

“Kitang-kita mo talaga iyong apprehension na dulot na rin na wala talagang nakikitang hustisya sa ilalim niya,” Human rights worker Sonny, who asked to be identified by his first name only, told Rappler.

“Hindi na sila umaasa na parang wala na, hayaan mo na lang,” he continued.

(You can really see the apprehension caused by the lack of justice under Duterte. The families do not hope anymore, they’re just letting it go.)

Sonny has been documenting human rights violations in the Philippines for more than two decades already. He started with Task Force Detainees of the Philippines, an organization established in 1974 or two years after Martial Law was declared, and went on to become a program coordinator for search and documentation for FIND.

His work involves gathering information about cases of enforced disappearances around the country. He and his colleagues talk to families and other potential witnesses to come up with comprehensive reports that can be used in potential cases, or any form of justice mechanism.

At the very least, families just want someone to talk to about their problems regarding their missing loved ones. It’s the most basic thing they can do in the face of challenges.

“Sinasabihan namin ang mga pamilya kung ano ang puwedeng gawin at kung saan puwede lumapit, so kapag nakakakita sila ng kaunting pag-asa, doon na sila nago-open up,” Sonny said.

(We advise families what they can do or who they can ask for help. When they see a glint of hope, that’s when they open up.)

Prospects under another Marcos

Nilda’s brother Hermon disappeared during the administration of Ferdinand Marcos. Forty-five years after his disappearance, the late dictator’s only son and namesake became president.

The victory of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. was preceded by decades of blatant efforts to rewrite history where social media played a huge role in spreading lies and trying to dismiss the atrocities during the Martial Law years.

But the state has the responsibility to ensure justice for its citizens. In the case of desaparecidos, section 21 of the law explicitly says that an enforced or involuntary disappearance is considered a continuing offense as long as the victim’s fate and whereabouts are still unknown.

“Since si [Marcos Jr.] ang presidente ngayon, he is the chief executive of the state, responsibilidad niya na bigyan ng katarungan, reparation, at even ipa-imbestiga ang nangyari sa mga biktima ng enforced disappearances sa panahon ng tatay niya,” Sevilla said.

(Marcos is the president now, he’s the chief executive of the state, so it’s his responsibility to give justice, reparation, and even investigate what happened to the victims of enforced disappearances during his father’s time.)

As it is, the President’s human rights agenda is virtually unknown. It was not included in his State of the Nation Address. He has not even named the new leaders of the Commission on Human Rights.

But for Sevilla, asserting their right to the truth will continue, no matter the circumstances.

“We won’t give up and be silenced by their indifference,” she said.

“Gusto pa nilang burahin sa kasaysayan, burahin ang collective memory ng victims, pero lalaban at lalaban kami,” Sevilla vowed.

(They want to erase history and the collective memory of victims, but we will continue to fight.) – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.