SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

“Gagastos tayo para sa Pilipino (We will spend for the Filipino),” President Rodrigo Duterte declared in an April 13 midnight address.

Steal or borrow, I don’t care, Duterte told Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III a week earlier. Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque was consistent in announcing what Duterte wanted – to give aid to all who needed help.

Millions of Filipino families struggling to cope with the coronavirus pandemic and lockdown took his word, and held on to his acclaimed “political will.”

Three months later, there are still many left behind, wondering if the cash aid they were promised would ever come.

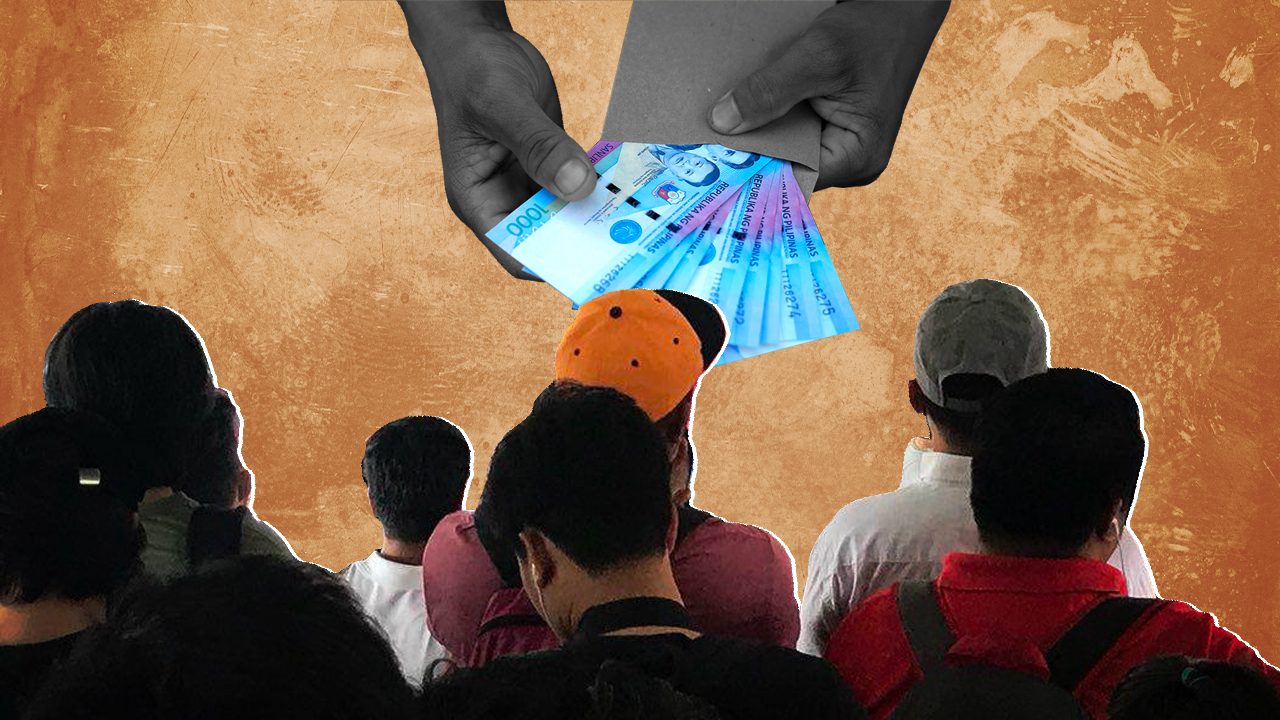

The government’s emergency subsidy program (ESP) was created under the now-expired Bayanihan to Heal as One Act, which promised cash aid of P5,000 to P8,000 to 18 million poor families a month for two months. The government had P200 billion to spend for it.

Come the second tranche, however, the original list was halved to exclude those who were no longer under enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) starting May. While the government added 5 million “waitlisted” families who were qualified but not included the first time, the law made no mention of eligibility dependent on quarantine levels.

The Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), the ESP’s lead implementing agency, consistently tells the public in its regular briefings that help is on the way.

DSWD top officials, with straight backs and monotones, appearing to be reading from a script, tell the camera: “Inaasahan naming mas madaming mapapamahagian ng tulong sa mga susunod na araw (We expect more will receive aid in the next days).“

But in the comments, the live feed shows comments one by one: “Kailan po dito sa amin (When will our area receive aid)?“

Unqualified

In Bulacan, there was a house with 5 families: 11 adults, and 9 children. All heads of the family except one were construction workers who had nothing to build.

“Ipinatigil ng engineer ‘yung gawa namin kasi nag-lockdown. Ang usapan naming mag-asawa, saan na kami kukuha ng pagkain? P600 ang sahod ko noon, wala na kaming natirang ipon,” said Ramil Olvinar, head of one of the 5 families.

(The engineer stopped our project because of the lockdown. The conversation between my wife and me revolves around where we are going to get money for food. My salary was P600 a day, and we don’t have any savings.)

When the government announced it had cash to give to families in need, the household did what they could to make sure their families would be included. The barangay officials who visited their house in April gave all 5 families one social amelioration card (SAC) each – which were photocopied – but they held on to hope they would be included.

Weeks passed and nothing came back. Even as guidelines said the officials would return to their houses, Ramil went to the barangay hall with his neighbor, hoping to follow up.

“Sinubukan naming magtanong sa barangay noong May. Ang sabi sa amin [ng chairman], wala kaming pangalan sa listahan ng mabibigyan. Hindi kami kasama. Halos maiyak-iyak kami noon,” said Ramil.

(We tried going to the barangay in May to ask. The chairman told us no names matched ours in the list of those who will receive aid. We weren’t included. We were close to crying then.)

Ramil held his breath as he walked home to his anxious wife. Once he told her, she couldn’t fight the tears like he did. Food at home had run out at that point.

Determining beneficiaries

While the DSWD said the original 18 million families included in the ESP were mostly based on the 2015 Listahanan – the government’s database of who and where the poorest families in the country are – the agency only gave to the local governments (LGUs) the number of SACs based on how many they knew to be poor in that area. The DSWD left it to the LGUs to decide who they were, as the agency believed they knew their constituents best.

This caused trouble not only for the poor families gunning for a limited slot, but also for the local officials who struggled to cater to all who were in need. (READ: Duterte chaos leaves barangay officials ‘helpless’ amid lockdown)

One week into April, Social Welfare Secretary Rolando Bautista acknowledged “shortcomings” in the program. He noted the system was imperfect because it is the “first time” for the nation to experience a situation like the pandemic.

During a Rappler Talk interview on April 28, former DSWD Secretary Dinky Soliman said the major misstep in the implementation of ESP is “unclear communication.”

Soliman said that the government was not clear when it first announced who would be part of the subsidy program.

“The announcement of higher authorities that this will be given to all 18 million people, and they gave P8,000 for NCR and everyone in NCR who think they are poor are expecting this. It made expectations rise,” Soliman said.

Soliman said that people can always claim that they are in need of support because they have lost livelihood.

Meanwhile, there were local officials reported to be politicking in deciding who will receive aid. More than 100 barangay officials are facing criminal charges for alleged anomalies.

Change of rules

The family of Wilma Belmonte was more than grateful to have received subsidy for the first tranche of the ESP. Her husband was a construction worker out of a job too, while she was a lactating mother to her 6-month-old baby. After receiving their P5,000 aid, Wilma spent most of it for things her baby and 4-year-old needed.

Even as the second tranche was meant for May, the first tranche was still being distributed well into May while the country waited for the government to decide when and how it would distribute the second. Roque first announced on April 24 that general community quarantine (GCQ) areas starting May 1 would be excluded for the next wave of aid, but there had yet to be a written set of guidelines.

Almost a month later, Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea released the presidential directive that the second tranche of aid would go mostly to ECQ families.

The final number of beneficiaries confirmed by a succeeding DSWD press release was 13.5 million – 8.5 million from the first tranche, plus 5 million wait-listed from ECQ and GCQ areas. Only 1.5 million families from GCQ areas were to be allowed consideration for the list, depending on their level of need.

Wilma’s family, who lives in Camarines Sur, was stripped of their slot in the program. Bicol Region was put under GCQ starting May 1.

“Nag-alala kami, dahil paano namin mababayaran ang mga bayarin sa tubig at kuryente? Hanggang ngayon sobrang nagigipit pa rin kami – pang-gatas ng mga anak namin, ang hirap makahanap ng pambili. Nakakahiram kami pero ang problema naman ang pambayad. Hindi pa rin kasi makabalik asawa ko dahil ‘yung pinapasukan niya di pa rin nag-o-operate,” said Wilma in a June 24 message to Rappler.

(We were worried, because how would we pay the bills for water and electricity? Until now, we’re struggling with our money – for our children’s milk, it’s so hard to find money. We’re able to borrow money, but the problem is in paying it back. My husband can’t go back to work because his company isn’t operating yet.)

Wilma sells online for the time being, although she finds it difficult to sustain due to lack of capital. Sometimes, the family is able to scrape funds together to buy some food.

“Ngayon, masuwerte kami at may pambili ng Lucky Me. Nakabili kami ng isang piraso ng noodles, ‘yun ang pinagsaluhan namin…4 kami, kaya kasya naman (Today, we’re lucky because we have money to buy Lucky Me. We were able to buy one pack of noodles, and we shared it…We’re 4 in the family, so it’s enough),” she said.

A Lucky Me pack of noodles retails at around P7.50.

‘Better, faster’ second tranche

On April 28, Bautista announced that the agency had partnered with the Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT) to facilitate automated subsidies for the second tranche.

It was in line with more promises to make the May aid faster and more efficient. The app “ReliefAgad” was launched two weeks later to allow families with SACs to register online.

Instead of transferring cash to LGUs which caused alleged anomalies, the agency’s funds would go straight to the Land Bank of the Philippines for partner financial service providers like GCash and PayMaya to disburse.

The long-awaited second tranche finally began on June 11 with 1.3 million beneficiaries of the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps).

The House of Representatives, meanwhile, took notice of problems in the ESP’s implementation. No less than House Speaker Alan Peter Cayetano and several other House leaders filed a resolution on June 15 calling for an investigation into delays in the distribution of aid.

By then, even the first tranche had yet to be completed, with around 500,000 beneficiaries still waiting for their aid meant for April, according to a Palace report. The number of families served for the first tranche has been hovering around 96% to 98% since May 24. The following tracker shows the distribution progress of the first tranche:

Based on the budget of P100 billion for the first tranche, data from the DSWD shows that around P1.2 billion has yet to be disbursed from the first tranche as of July 14.

The DSWD asserts that the first tranche is “complete” at 98%, citing various reasons for the discrepancy, such as discovering disqualified beneficiaries and those who willingly waived their aid.

However, the latest Palace report showed that the 17.9-million count of estimated beneficiaries as of June 29 was about 10,000 less than the original number of beneficiaries stated in the omnibus guidelines for social amelioration. The government has yet to report the complete breakdown of removed beneficiaries for the first tranche after adjustments.

ReliefAgad closed on June 24 with just 4.3 million registrations for the second tranche – unclear how many of whom are qualified beneficiaries. Bautista said not to worry if the beneficiaries did not get to register via the app, as the LGUs still have the lists of who are included. Even with LGU control over the lists, Bautista still guaranteed that local officials can no longer commit anomalies in the cash distribution.

DSWD proudly noted that electronic payments would not only help transfer funds faster, but also help mitigate COVID-19 transmission. However, lawmakers pointed out that quick fund transfers are not enough, as rural areas may not have banks or automated teller machines (ATMs) available for withdrawal.

For Sonny Africa, executive director of advocacy group IBON Foundation, changing the mechanism of distribution created more problems. He questioned the government’s move to create a new system when it already had infrastructure during the first tranche.

“Kung nabigay na ‘yung first round, may infrastructure na diyan e. So kung ang ini-issue nila ay who gets what, gamitin ‘yung [list]. Hindi na kailangang gumawa pa ng bago. If you have an existing infrastructure na at kung ang hinahabol nila ay listahan ng mga tao, balikan na lang ‘yon,” Africa said.

(If they were able to give the first tranche, they already have the infrastructure. So if their issue is who gets what, use the list. There’s no need to create a new one. If you have an existing infrastructure and you’re looking for the names of people, you can go back there.)

According to Africa, the government should be focusing on figuring out why there are still beneficiaries who have not yet received the financial aid.

“Make up for the fact why there are still people who have not received the financial aid yet. There’s no need to reinvent the wheel. If it’s really a problem of documentation, the fact that there were some 18 million who received financial aid through various mechanisms, that means they already have the documentation,” Africa said in a mix of English and Filipino.

‘Napipilitan’

Africa also believes that the government is making life even worse for poor Filipinos during the pandemic.

“Actually, it stems from the original sin ng attitude ng government sa emergency relief. Their original sin was napipilitan sila na magbigay ng emergency relief. Masyadong matipid at masyadong mabagal at magulo ang pagbigay nila,” Africa said.

(Actually, it stems from the original sin of the attitude of the government towards emergency relief. Their original sin is they feel compelled to give emergency relief. Their distribution is insufficient, too slow, and chaotic.)

Africa said that the government should not be hesitant to disburse funds for financial aid during the pandemic. They can always find ways if they really want to help, he added.

“Ang argument nila ay nagtitipid tayo ngayon dahil hindi natin alam kung hanggang kailan matatapos ang [pandemic]. Para sa amin, kumawala ang gobyerno sa pag-iisip na walang pondo. May pondo kung gusto nila magpalitaw ng pondo,” Africa said.

(Their argument is they’re being economical because we don’t know how long this pandemic will last. For us, the government should veer away from the thinking that there are not enough funds. There will be funds if they want to find them.)

For Africa, the government can set aside the budget for the infrastructure projects this year and realign the funds for social protection programs.

“There are a lot of infrastructure projects that are irrelevant now amid the recession and tourism decline. More than half of the funds would be spent for imported construction materials, contractors, and workers. These projects won’t help the Philippines now. The funds for these should be given to those who are in need now,” Africa said in a mix of English and Filipino.

Africa also said that instead of borrowing funds from international banks such as the World Bank and Asian Development Bank, the government should be talking to them to defer loan payments for now so the country can use the money as financial aid to affected Filipinos.

“Anong masama na sabihin sa kanila na developing agency kayo na gamitin namin ang pondo na pambayad sa inyo for cash support. Of course, magrereklamo ‘yan kasi bangko yan. But the point is… they claim to be a development organization, then be like a development organization,” Africa explained.

(What’s wrong with telling them that we will be using the money first, intended as loan payment, for cash support instead. After all they are developing agencies. Of course, they will protest because they are banks. But the point is, they claim to be a development organization, then be like one.)

‘Listen to people’

For Soliman, getting people involved would better help facilitate the distribution of cash aid.

According to Soliman, the government should listen to people because they are in a better position to say what they really need. She argued that officials should veer away from the notion that they would take advantage of the situation. The people themselves can tell the government how the distribution system should be done.

“You just have to be open to feedback [from the] citizens. They’re not helpless people that are just waiting to be given. Provide the list publicly in a barangay so they would, and they can tell us why the family is there,” Soliman said.

While this system is prone to abuse, Soliman said that it is innate of people to help one another in times of need.

“While there will be outliers of abuse stories…People know how to help one another. It is not the common thing of getting one over. Hindi manloloko ang tao. Mayroon, pero hindi ‘yan ang general sentiment ng tao,” Soliman said. (People are not cheaters. There are some, but that’s not the general sentiment of the people.)

Aside from getting feedback on the ground, Soliman said there should be collaboration between the DSWD and LGUs. “The national agency and LGUs sitting down to plan and address the needs of the people,” she said.

Just one adult in Ramil’s house is able to return to work as a tricycle driver, as Bulacan has eased lockdown restrictions. He is all the 5 families depend on for now.

Ramil still looks to his government for help. “Sana sa second wave mabigyan kami kahit papaano. Kahit isa lang sa ‘min,” he said. (I hope we’ll receive aid in this second tranche. Even if it’s just one of us [families].)

Meanwhile, Wilma doesn’t mind enduring hunger. “Nag-message ako sa DSWD, kung hindi na kami mabibigyan, kahit hindi pera, kahit tulungan na lang mga anak ko – gatas, vitamins, diaper, at makakain nila, kasi kami ng asawa ko, kaya namin kahit hindi kumain.”

(I messaged the DSWD that if they won’t help us anymore, even if it’s not financial aid, maybe they could just help my children – milk, vitamins, diapers, and food, because my husband and I can get by without eating.)

In a pandemic with no end in sight just yet, Wilma calms her children with empty stomachs, and waits for a reply to her message. – with a report from Michael Bueza/Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.