SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

He’s been called “incompetent” as the Philippines continues to battle a fierce pandemic. He’s been criticized for having no sense of honor, blasted by lawmakers for refusing to resign in the face of failure to deal with a massive health crisis. He’s been accused of being too political, doing the bidding of presidents, both past and present.

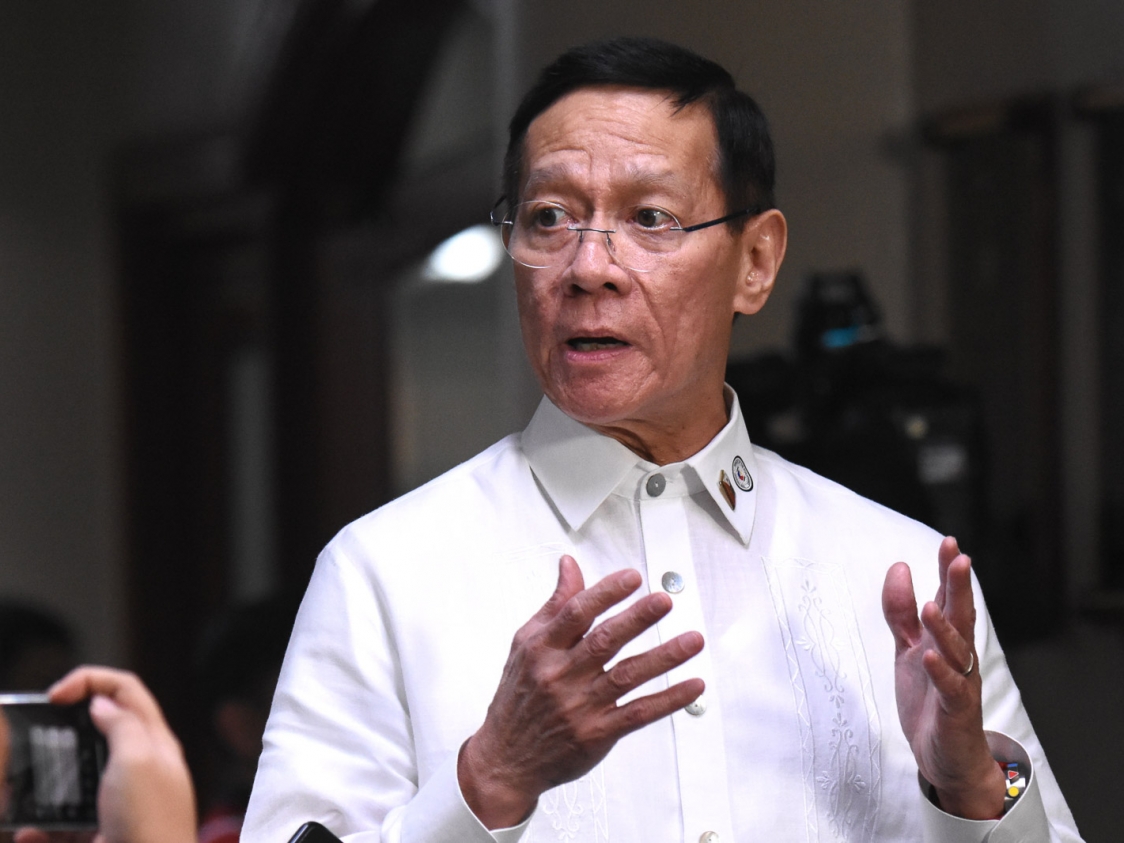

But of the many things said about him, what probably stands out the most is that Francisco Duque III is a survivor.

Accumulating two-decades-and-a-year in government service, Duque has ridden through waves of controversy – the latest seeing him simply “admonished” for billion-peso anomalies in the corruption-racked Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth), where he sits as chairman.

Duque has survived 3 presidents and held prime positions in PhilHealth, Civil Service Commission (CSC), Government Service Insurance System, and the Department of Health (DOH).

A medical doctor who obtained his medical degree from the University of Santo Tomas and a master’s in pathology, on top of training in immunology from Georgetown University, Duque has strong credentials to lead the country’s fight against the coronavirus pandemic.

But the Philippines – among the countries with the longest quarantines still in place – entered the 6th month of the pandemic with over to 265,000 COVID-19 cases, the highest number of confirmed cases in Southeast Asia. Certainly not a source of pride for a man who is the first person to twice hold the country’s top health post.

Hurt by resignation calls and what lawmakers called a lack of competent leadership and strong will to stamp out corruption, Duque complained he’d been losing sleep.

“My public service record is an open book,” he said. “If there is a single thread of conclusive evidence of my involvement on any and all issues, then let the axe fall.”

Those who have worked with Duque describe him as a public servant whose long career in government has failed to prime him for his biggest challenge. Instead it has shaped his defenses, placing him on thin ice as a pandemic continues to swirl nationwide.

Ties to Arroyo

As a second-generation health secretary, the worlds of medicine and government had long been laid out for Duque after his father, Francisco Duque Jr, held the same position under former president Diosdado Macapagal.

Following the paths of their fathers, Duque, who goes by the nickname “Pingkoy,” launched his career in public service at the behest of Macapagal’s daughter, Gloria Arroyo.

The two families are known to be close, with Arroyo’s mother – former first lady Evangeline Macaraeg – sharing the same home province of Pangasinan with the Duques. It was through Arroyo’s appointments that Duque learned the ropes of government service.

Throughout his 21 years in government, Duque has accumulated experience in various agencies. Though he is most known to have been PhilHealth president from 2001 to 2004, and later, health secretary from 2005 to 2010, Duque’s first known government stint was as Arroyo’s permanent representative to PhilHealth in 1999. Arroyo was still vice president at the time and held the concurrent post as social welfare secretary.

Before becoming PhilHealth president, Duque served some 3 months as DOH undersecretary under former secretary Manuel Dayrit. It was a period of initiation for him.

As health secretary, Duque rebranded existing national programs under his “Formula 1” and “Formula 1+” plan. As PhilHealth chief, he tried to increase coverage of indigent populations by convincing local government executives to enroll their indigents with the state insurer.

Duque returned to the DOH in 2017, after Duterte appointed him following the Commission on Appointments’ rejection of his predecessor, Paulyn Ubial.

Asked in June why the President trusted Duque despite lapses, Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque said Duterte knew the Duque family “very well” and was certain they would not steal from government. Roque said Duque’s brother, former Philippine Coconut Authority administrator Gonzalo “Gonz” Duque, was “very close” to Duterte as the two were graduates of the San Beda Law School.

But one post that would mold Duque greatly was that of CSC chair. It was the 4th and final ranking position Arroyo appointed him to, just before she stepped down as president in 2010. He held the post throughout the Aquino administration, up until 2015.

Blame game

At the CSC, Dayrit said Duque presided over decisions on cases involving people in the civil service. “So one of his views is that his subordinates have their own accountabilities.”

This may partly explain why Duque tends to take subordinates to task and blame them for shortcomings in his department, even castigating them publicly before reporters and the President.

In a Senate hearing on February 4, just 5 days after the Philippines confirmed its first COVID-19 case, Duque constantly turned to his staff for answers to lawmakers’ questions about contact tracing.

When it became apparent the DOH’s epidemiology bureau failed to trace all 331 passengers on board a Cebu Pacific flight that had on board the country’s first COVID cases, senators asked why Duque seemed to discover this only during the hearing.

Instead of owning up to the lapse, Duque told the Senate he was “really worried” about an “institutional competency problem” and “lack of transparency” in his department.

As health secretary, Duque said his task was to keep an eye on the big picture and “more strategic interventions.” He expected his staff to have “the competence – that they already knew what they are doing, [that] they are familiar with the protocols.”

The same thing would happen a few months later in May, when an angry President Rodrigo Duterte threatened to fire DOH staff over delayed compensation for health workers who died or were severely infected by COVID-19. Duque’s initial response saw him joining the blame game, saying he was “embarrassed” by the oversight.

“These families have lost their loved ones, and yet my people dilly-dallied as if they had no sense of urgency. That’s what makes me feel bad, Mr President,” he said in Filipino.

Duque would later post on Twitter that while he was disappointed by some members of his team, he acknowledged that this was still his responsibility as health secretary.

Who’s accountable?

This tendency to blame others made working for Duque “very difficult” at times, health sources said. As head of a large department, Duque admitted in various hearings that he wasn’t one to be bogged down by details.

As Secretary, Duque would instead often limit himself to dealing with the agency’s executive committee composed of undersecretaries and assistant secretaries. He seldom engaged with other offices working “downstairs” or the agency’s 16 bureaus and services.

While this may have worked for the department’s day-to-day operations, it exposed weaknesses in the Philippine’s pandemic response. As a result, the health chief often blamed those working for him, sinking the morale of an agency he promised to boost.

“We see on TV how he responds. He has the propensity to blame it on other people…. I don’t know how he can come to work the next day knowing he said all those things,” an official said.

Duque’s reflex reaction to have workers answer for their own has cast a shadow on his public image. Frustrated by the country’s pandemic response, Filipinos called on the health chief to resign out of delicadeza, using the hashtag “#DuqueResign”. The call hasn’t gained momentum, however.

The tendency to deflect put Duque at loggerheads with senators – including Duterte’s allies – who believed he should assume responsibility for gaps in responses by the DOH and PhilHealth.

In particular, senators recommended criminal complaints be filed against Duque for malversation of public funds or property, violations of the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, and two more tax laws after billion-peso anomalies were linked to PhilHealth.

Yet Duque has repeatedly rejected these allegations, insisting he should not be held accountable for the agency’s lapses. “The Senate committee made baseless findings on mere allegations alone. I was impleaded…when I was not even part of the deliberation and did not sign the said resolution,” he said.

“Not even a shadow of my signature has turned up in the contested resolutions.”

Duque in the past also dismissed instances that, according to his critics, reflected “failed leadership.” Once asked by a reporter if the gaps in contact tracing were indicative of such failure, the health chief answered in the negative and instead likened himself to a conductor.

“It is not right for the secretary of health to go into those operational details because the secretary of health orchestrates everyone. It’s like when you orchestrate an ensemble, I’m not going to get somebody to teach somebody to play the violin. I already expect that he knows how to play the violin as the orchestrator,” Duque said.

This belies an administrative mindset in his approach to public health, perhaps shaped by his past experiences before he joined government.

From 1989 to 2000, he’d been dean, associate professor, executive vice-president, and chairman of the board of the Lyceum Northwestern University owned by his family in their home province of Pangasinan. He was also president of the Pangasinan Medical Center in the early 90s and administrator of the Lyceum Northwestern University General Hospital from 1991 to 1998.

Political and loyal

Years in government taught Duque the skills needed to survive several administrations and controversies.

Under Duterte, Duque has stuck to messaging. When asked about matters pertaining to the President’s health, Duque’s standard answer: He is in a “good state of health.”

Neither would he refute the President even on other health-related matters. When asked to comment on Duterte’s controversial drug war, for example, he opted to describe it as “well-balanced” and “coordinated.” Critics of the drug war have said that drug addiction is a health issue. And after Duterte claimed that gasoline could be used as disinfectant, Duque saw no need to correct him, saying instead that the President was “only joking.”

Several officials who worked with Duque described him as having strong political instincts. The health chief understood the value of optics and knew how to cover his back.

A day after the Philippines confirmed its first COVID-19 case, lawmakers on January 31 called on the DOH to recommend a travel ban as a “prudent” decision. Duque argued it would be “tricky” to single out China and risk repercussions when other countries reported coronavirus cases, too.

The health chief was careful not to contradict the President’s response the night before when he told reporters he was “not inclined” to ban travelers from China since it would be “unfair.” (Two days later and after a public outcry, the government declared a China-wide travel ban on February 2.)

On July 13, when the DOH missed its daily update due to a “significant volume of data gathered,” a Zoom meeting was held to discuss how the department would explain the increase in reported cases, recoveries, and deaths in the country. The department was particularly concerned about the higher number of 162 fatalities and worried this would trigger a public panic.

A source present at the meeting said Duque and other DOH officials were worried about optics before Duterte’s State of the Nation Address, with the health chief “jokingly” saying the President’s office wasn’t happy with the backlogs.

Those present discussed the possibility of spreading out the number of deaths, but other staff present pushed back. In the end, all validated deaths were reported the following day, along with all recoveries and confirmed cases.

Rappler repeatedly sought Duque for comment through texts, calls, and messaging app, but he has not responded as of posting.

As PhilHealth president and CEO, Duque was also embroiled in controversy when the funding and timing of a program he initiated, “Greater Medical Access” (GMA), was questioned.

A 2004 Newsbreak report found P6 billion would be needed to cover a targeted 5 million members, though the proposed budget for the Office of the President in 2004 allocated only P500 million as premium subsidy for indigents.

Critics likewise questioned its timing as PhilHealth cards distributed to members bore the image of Arroyo and were supposedly distributed to bolster her bid for a second term.

When the issue was raised again in recent Senate hearings, Duque “strongly denied” allegations the program was used as a tool for political gain. He asserted these were distributed based on an Arroyo executive order “so there’s no correlation between the PhilHealth program and the elections.”

Duque has also defended himself against recent characterizations of himself as a “politician,” saying it was “unfair” to be called such as he’d only been acting upon the President’s instructions.

Officials who worked with Duque said this explains his longevity in office. “If he is told to do something, he’ll be a team player. He won’t contradict,” a source who worked with him said. “He knows when he’s not the most powerful person in the room.”

Duque is a fierce supporter to whoever is in charge, and “will say and do things to show his loyalty.”

At the pleasure of the President

While Duque’s actions may have ignited public criticism and the ire of lawmakers, resignation is not an option because he values his legacy and name. Besides, the loyalty and obedience Duque showed through the years have earned him the solid backing of two presidents.

Duterte and Arroyo, who happen to be strong allies, have carried him through waves of controversy and continue to hold him up to this day. No less than the President declared that so long as he is not corrupt, the health secretary will enjoy his “full trust.”

For a country besieged by a pandemic, having a top health official who is loyal and “not corrupt” is simply not enough. DOH insiders said Duque’s predecessors who had extensive experience in public health would have been more adept at dealing with the current crisis. These is a strength that Duque does not have, yet he remains to be the President’s choice.

For a man who’s built a life in government service, the President’s blessings are probably all that Duque needs.

After all, he vowed to continue serving at the pleasure of the President. Until then, Duque remains safe – unless of course, Duterte changes his mind. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.