SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[FRONTLINERS] ‘May kasal pa ako, Lord!’](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/76F7393EF34F466F8D0420CCA54851BF/img/5E4B84ED27FA4BC59134B179527E6FBA/Frontliner-Mica-Bastillo-April-20-2020-009.jpg)

MANILA, Philippines – Tuesday nights in her tent in her family’s front yard, counting the hours to Wednesday morning, are the hardest for Mica Bastillo.

Crouched on a wooden cot padded by a thin mattress from the private clinic she recently closed down, she scans her Bible for words to assure herself she would survive this pandemic alive. It’s also her way to dispel the anxiety that comes from anticipating what’s coming and which robs her of the rest she sorely needs.

The summer rain that fell beat on her makeshift “quarantent.” Shower curtains made up the walls and roof of her little shelter, even as the puddle from the garage had started to seep into the carpet on her cement floor.

She reminded herself to buy some waterproof flooring – perhaps those inch-thick rubber mats – on Thursday afternoon after she got out of her 24-hour shift at the hospital.

The tent was her mother’s idea. Staying inside their house was not an option for her because her father, a senior citizen, has hypertension, and had battled pneumonia and heart failure in 2017. One of her sisters has a congenital heart disease, and is still awaiting surgery. Her 4-year-old nephew could not be told to stay away from her.

They took a clothes rack and set it a couple of meters parallel to the front wall of the house. Her brother drilled holes on the wall and inserted metal rods connected to the two ends of the clothes rack. They draped their shower curtains over the clothes rack and the metal rods for Mica’s “quarantent,” as the family calls it.

It’s cool and breezy, but it gets hot at midday and Mica is beset by bugs at night, but she prefers it to the dormitory she would have shared with a handful of other health workers.

“It’s for my sanity, and to give me a semblance of normalcy,” she said.

Luckily, there’s a separate toilet and bathroom in the yard, allowing Mica to stay completely away from her family as she waits out the pandemic outdoors.

Into the front lines

On Wednesday mornings, at around 8:30 am, the shuttle chartered by the Pasig government picks Mica up at the gate of their home in Marikina to take her to Pasig City Children’s Hospital, also known as Child’s Hope hospital, which, since early April, has been the referral center for COVID-19 patients.

That was the first blow. Mica and her fellow pediatricians at Child’s Hope found out only on the third weekend of March that their hospital would be turned into Pasig’s hub for coronavirus cases. That meant they had barely a week to reorient themselves about their new job.

Doctors with specializations cannot just switch practices, and the idea upset Mica.

“The last time I handled an adult in-patient was in 2009. We are pediatricians. What if something happens to the adult patients under our care?” Mica said, sharing her and her colleagues’ apprehension when they first heard the news.

At some point Mica knew she would be called to handle coronavirus patients, but she didn’t think it would be that soon. It was internal medicine practitioners first, then maybe surgeons, before pediatricians like her.

Mica gave up one of her private clinics and then joined Child’s Hope in May 2019 because aside from the financial stability it afforded her, she really loves caring for children and watching the life resurge in them after a bout with illness. She never imagined this job would put her in harm’s way.

But when Child’s Hope became Pasig’s COVID-19 referral hospital, Mica was thrust into the pandemic’s front lines, and she did not feel she was ready for it.

“Today I felt like losing my home, and then sent to a battle I was not equipped for,” she said in a Facebook status post on March 23. She made black her profile picture.

But not one to turn her back on her sworn duty, Mica psyched herself up for her new role. She told her family about it, talked about how to separate herself from them without having to move out.

Although the city government offered accommodations near the hospital, Mica couldn’t bear not seeing her family until the pandemic subsides. The “quarantent” was her best compromise.

War zone

The city government enlisted general practitioners, and Child’s Hope itself recruited internal medicine practitioners before opening day to directly handle confirmed coronavirus cases. It took the main burden off the pediatricians still on duty.

Mica felt relieved, but she realized it didn’t really change her situation, except that she – already a consultant and diplomate of the Philippine Pediatrics Society – would be relegated to a role similar to an intern’s.

“You’re there but it feels like you’re no longer part of the effort to fight the disease, so I felt like, ‘Am I really a frontliner?’” Mica wondered.

But those thoughts disappeared the moment she walked into Child’s Hope for her first shift on COVID-19 duty.

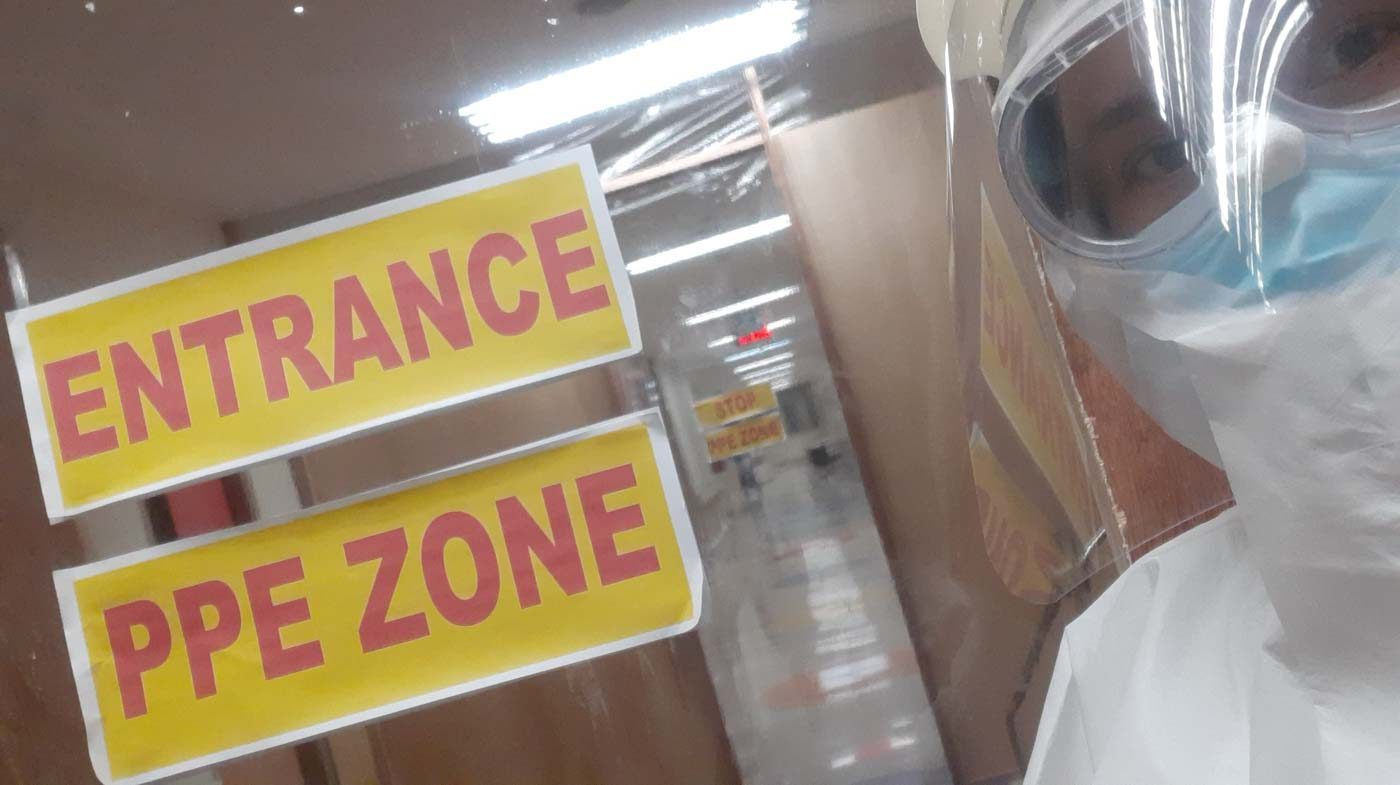

She could hardly recognize the hospital she had called “home” for the past year. Everyone was in personal protective equipment (PPE), especially those working on the floor for confirmed patients. Plastic sheets and other partitions separated the “clean” areas from what was considered the war zone.

“Anyone coming to the hospital sick is presumed to have COVID-19 unless proven otherwise. I was like, ‘Okay, I really am a frontliner now!’” Mica said.

Her job takes her to the confirmed patients’ floor but on the opposite wing, where she checks on suspected cases or those past the worst symptoms, and are considered in recovery.

To do this, she needs to put on level 4 PPE – the complete set with a coverall or “bunny suit,” surgical cap, N-95 mask, scrub suits, goggles, face shield, double gloves, dedicated shoes, and shoe covers.

Breathing inside a PPE

“I’m always close to a panic attack when I start putting on the PPE. Because I have a tiny face, the edge of the N-95 mask presses into my neck, and of course I have to tighten it so that it clamps onto my nose, too. And then the bunny suit covers my face all the way to the top of my nose. It feels like being strangled.”

She could hardly breathe inside the PPE, says Mica, who has a small, delicate frame.

“I worry that panic would hit me any moment and I would suddenly just tear myself out of that PPE.”

Because health workers, including doctors, are issued only one PPE set per day, there’s no getting out of it until they’re done for the day. They can’t loosen any part of it to get more air, can’t unzip to go to the toilet, and can’t even take off the mask to eat or drink anything.

On her first day, Mica could barely speak to the patients whom she needed to ask detailed questions to write comprehensive updates about their condition.

Just slouching to jot something down on the patient’s file constricted her airway. She felt like she was being strangled, would either suffocate, or go insane. On that first day, she lasted only an hour-and-a-half in her PPE.

“Imagine the nurses. We doctors only need to don the PPE when we make our rounds. The nurses do everything for the patients – feed them, wash them, bring them their medicine – because no relatives are allowed in the hospital. So they have to stay in the suits their entire shift, which is 12 hours straight,” Mica said.

Although her shift is a straight 24 hours starting around 9 am on Wednesdays, her work as a “hospitalist on duty” allows her a lot of standby time, during which she is only required to wear an N-95 mask. She doesn’t have to don the entire suit of armor.

She’s not needed back at the hospital until the next Wednesday, which means the rest of the week, Mica is cooped up in her quarantent, relishing the nearness of her family as she swats mosquitoes that seem immune to repellent lotion.

Alone with her thoughts, Mica’s closest confidant is half a world away – her fiancé Kirby Casillan, an occupational therapist on the front lines of battling the same pandemic in Doha, Qatar.

Special night

They first met when she was 15 and he, 17. They were actors in a Christian theatrical group called Master’s Commission Philippines.

“I’d see him there, we’d say ‘hi, hello.’ Mere acquaintances. When my sister and I left the group, I thought that was it. Then we got reconnected through online chat in 2011 or 2012, and we’d talk. Then in 2015, we were supposed to meet up but it never pushed through. Something happened and he suddenly disappeared,” Mica recalled.

Kirby resurfaced in October 2019, and this time, he was direct and serious. He was coming home in November to get to know Mica better, “and his intention was for marriage” as a good born-again Christian man ought to tell the woman he loves.

Sure enough, Kirby was back in the Philippines on November 28. He introduced Mica to his parents, and she introduced him to hers. “Kailangan pumasa ka sa kanila (You need to convince them),” she told him, because she already was convinced about him. She knew where they were headed.

When he was still in Doha, Kirby got Mica to agree to have dinner with him at a fine dining restaurant, and on December 10, she obliged him. He said he had reserved a regular table at the restaurant but when they arrived, the staff told them that someone had just canceled a reservation for a private room, and they were free to take it. They did.

There were red balloons in the room and rose petals on the floor, and Mica wondered what the occasion was that the family who made the reservation suddenly called off.

“I was thinking it was a family! Looking back it was pretty obvious but I had no clue!” Mica said. Kirby even asked her if she had any inkling what was going to happen that night, perhaps trying to calm his own nerves, but she was oblivious.

It was a 5-course meal and she was baffled that the restaurant staff kept taking pictures at every turn. When it was time for dessert, a waiter served her a plate on which was written, “Will you marry me?”

“Then Kirby got down on one knee but couldn’t say a thing. Sabi ko sa kanya, ang daldal-daldal mo tapos ngayon wala kang masabi (I told him, you’re quite a talker and now you’re speechless)?” Mica recalled, laughing.

“He was crying and I was crying, then finally he was able to get it out. He asked me to marry him and I said yes.”

The future

They made plans. She was going to look for a job in Qatar and he would help her with her papers. That would secure her a Qatari visa. Otherwise, they would wait until the wedding and get her a spouse’s visa afterwards. Either way, it was set. They were going to get married on June 3, 2020.

But until then, they had to part because Kirby had to return to his job in Doha.

“I was already a tearful mess at home and I couldn’t bring myself to see him off at the airport,” Mica recalled when Kirby flew back to Qatar on December 13, just 3 days after he proposed.

At the time, reports of a new virus spreading in Wuhan, China seemed remote and had nothing to do with their happiness as an engaged couple.

By March 9, the Philippines already had 20 confirmed cases of the novel coronavirus, and it was one of 14 countries upon which Qatar imposed a travel ban that day. From then on, no one from the Philippines would be allowed to enter the Middle Eastern country while the pandemic lasted.

Kirby had then already secured a leave of absence from work for his wedding, and as a Filipino he would be allowed to fly home to the Philippines. The problem was if he did, we wouldn’t be allowed back into Qatar, and he would be considered resigned from his job.

He had to raise the subject with Mica: should they postpone their wedding?

Doubts

“Was I disappointed? Yes! I was devastated!” Mica said.

Although she had known Kirby almost all her life, their engagement had been pretty sudden, and she could not help but get paranoid over this curveball.

“Did he still want to marry me? Seems funny but that’s what was on my mind.”

Although she knew none of it was Kirby’s fault, Mica didn’t talk to him for a full day and night, until something he told her during their last call sank in.

“‘Don’t you realize this is hard for me, too? This is much more difficult for me than you may think,’ he told me, and I realized that, yeah, I’m not the only one who’s devastated by the idea,” Mica recalled her conversation with Kirby.

“He just had to reassure me that he wanted to marry me, and that he will marry me.”

Call the suppliers

In the succeeding days, the number of coronavirus cases in the Philippines kept rising and the curve shot up, prompting the government to declare a lockdown over Metro Manila on March 15, then over all of Luzon island on March 17, as other provinces, cities, and municipalities followed suit.

It was clear what she had to do. One by one, Mica called the wedding suppliers and asked for a change of date. She and Kirby were thinking of moving it to November, but who’s to say if the pandemic will be over by then?

“The travel ban is indefinite. Rumors are this might go on for a year. Oh my gosh! Another year? My disappointment came crashing on me all over again. And so Kirby and I talked again, and we resolved it again.”

Soon, Mica came to accept the reality. None of this is within her or Kirby’s control, so why sweat it? For now, Kirby is a constant face and voice on her phone, and will probably be so for the rest of the year, maybe even beyond – Kirby, the man who would have become her husband this June.

“But thank God for technology,” Mica said. In quarantine for the rest of the foreseeable future, she is grateful for a way to keep in touch with her loved ones – those inside the house she cannot enter, and the one overseas whom she cannot yet marry.

‘Are you worried for me?’

It was Thursday evening, April 16, and Mica was in her tent resting from the shift she had just finished when a message on one of her chat threads with her colleagues delivered what was probably the hardest blow to her yet.

A fellow pediatrician on her shift had tested positive for COVID-19. Contact tracing suggested that Mica, too, could have the virus, and she needed to be tested as soon as possible.

“The other Wednesday, we were together when we put on our PPE. We did our rounds at the same time. I came across her in the ladies’ room once after brushing my teeth and we talked a little, and of course I wasn’t wearing a mask then,” Mica said, recalling her encounters with that colleague.

Mica had no symptoms except for a slight discomfort in her throat that could have been because of the N-95 face mask, a brief headache the previous weekend, and occasional cough and cold.

Calmly, she picked up her phone and messaged Kirby to tell him the news.

“He was on duty at their hospital and I couldn’t just call him. I sensed that he was anxious so I told him, ‘Don’t worry, God is with us. I know he won’t abandon us.’”

Kirby video-called her during his break. “Are you worried for me?” Mica asked him.

“Of course, Love!” Kirby replied.

Between Mica and Kirby, who both grew up in born-again Christian churches, they have what must be an army of “prayer warriors” who would storm the heavens in supplication for Mica.

That evening, Mica’s aunt, who is a missionary, called when she heard what happened, and she listened in as Mica told her family, from outside through the window, that she needed to get a swab test the next morning because she might have COVID-19.

A devout Christian family, the Bastillos were taken aback but were on their knees in no time, dousing their anxiety with prayer.

Her aunt, on speaker phone, led the prayer and said that they should have communion. Born-again Christians cut pieces of bread and pour some wine or grape juice for everyone to share as they recall Jesus Christ’s last supper, his hour of greatest distress, knowing he would die a gruesome death the following morning.

Christ’s last supper was a Jewish passover dinner that foreshadowed the shedding of his own blood to mark the doors of believers’ souls, so that the Angel of Death – sickness, pestilence, despair – would pass over them and not take them, Mica’s aunt, the missionary, reminded everyone.

Mica’s share of the bread and juice were placed on a tray outside the door of their house. Out in the yard under a cloudy sky, a safe distance away from her family, Mica joined them in this holy communion, praying hard that she would indeed be passed over.

Faith

“I was surprised at how calm I was when I found out that I had been exposed to someone with the virus,” Mica said, recalling how she had been much more shaken when she first learned about Child’s Hope getting converted into a referral hospital.

“Come to think of it, things are not as bad as they seemed initially. Sometimes you just have to roll up your sleeves, and you realize your mindset plays a big role in how you respond to things.”

Mica’s most recent Wednesday shift had been a lot better for her. Nothing had changed – except her mindset.

It is her duty as a doctor. It is the right thing to do. And she’s all prayed up, nothing that she needs to remind God of, as if he needed to be urged to protect and care for her.

“Duty. It’s a word we have taken for granted. We refer to it as our turn to work in the hospital and render our services. But now I’m perceiving it for what it is. We have a duty to fulfill in the service of the people,” Mica told Rappler.

“Honestly, in light of so many healthcare workers getting sick, it makes me scared at the same time. It’s quite a scary and exhausting time to be a doctor. So we just need to protect ourselves and serve who we can – being cautious, but not anxious,” she added.

She was prepared for the battle after all. Everything she was taught growing up in church, everything she’s read in the Bible – they’re all within her, answers she had known long before this pandemic raised the questions.

When she faced the PPE again and was about to stuff her face into an N-95 mask, she found that she could shush the creeping panic. She realized that if she breathed through her mouth, she didn’t feel so starved for air. It didn’t occur to her before, when she was freaking out.

Last Wednesday, she was able to stay in the PPE for more than two hours, an achievement she feels quite proud of.

Coming to terms

One afternoon when she was in her quarantent and it rained so hard she thought it would cave in, she felt the urge to cry. But she realized it was self-pity and she shushed that feeling away, too. Self-pity never helped anybody.

Instead, she looked at her quarantent and thought of what she could do to make it better. If she was staying in it for a while, she might as well do some home improvement. She got electric traps for the mosquitoes, thought of adding a second layer of tarpaulin on the roof, and didn’t forget that thicker matting for the floor.

On Friday, April 17, Mica found herself back at Child’s Hope with the other frontliners from her shift as they all got tested for the coronavirus.

“Hey, the swab was uncomfortable, ha? Like a really deep nasal cleanse!” Mica quipped.

It takes a week for the swab test to yield results, and she won’t find out hers until around Thursday, April 23.

“If in case it’s positive, then I just pray the symptoms will be mild,” she said, though of course she hopes for a negative result.

“What if I don’t make it?” she used to wonder before she came to terms with her new reality. Now, she is done overthinking things. She has to make it, and one thing she can do is to believe that she will.

“May kasal pa ako, Lord (I still have a wedding, Lord)!” Mica used to say in despondence. Now, she does so in defiance. – Rappler.com

TOP PHOTO: Pediatrician Mica Bastillo inside her ‘quarantent’ in the front yard of her family’s house in Marikina, where she stays when she’s not on duty at the Pasig City Children’s Hospital. Photo courtesy of Mica Bastillo

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.