SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Months after its creation in 1986, the Presidential Commission Good Government (PCGG) saw tangible results of its quest for the return of the illegal assets of the Marcoses and cronies.

It negotiated the first compromise deal with crony Jose Yao Campos, a Chinese Filipino entrepreneur who owned the controlling interest of United Laboratories Inc., a major drug firm, for the return of the Marcos assets listed under his name.

Campos, low key and unassuming, was probably the most cooperative among the known Marcos cronies. Unlike other cronies who chose to slug it out with the post-Marcos government, Campos cooperated fully in surrendering the Marcos assets under his name. Marcos used him mainly as caretaker of those illegal assets.

A friend of the dictator, Campos surrendered to the PCGG the 197 titles representing pieces of real estate property in Metro Manila, Rizal, Laguna, Cavite, Bataan and Baguio City, and P250 million ($5.3 million) in cash. The pieces of real estate property have a combined value of over P2.5 billion ($52.5 million). (READ: Recovering Marcos’ ill-gotten wealth: After 30 years, what?)

In 1987, the PCGG recovered P375 million ($7.9 million) from the accounts of Campos and Rolando Gapud, reputedly the dictator’s financial adviser, in Security Bank and Trust Company, a local commercial bank. Decades later, the Honolulu court decided to compensate the human rights victims of the Marcos regime and ruled the sale of two pieces of property in the US to pay them. They were listed under Campos’ name.

Among the Marcos assets under Campos’ name, which the PCGG sold to the private sector, were: the Dasmariñas property in 1994 for P200 million ($4.2 million); IRC Antipolo property in San Isidro in 1995 for P27.6 million ($580,000); the IRC Antipolo property in Victoria Valley Subdivision 1996 for P35.2 million ($740,000); Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company shares in 1999 for P74.2 million ($1.6 million); and Anscor and PLDT shareholdings in 2005 for P41 million ($860,000).

Also sold were: Manila Bulletin shareholdings in 2008 for P163 million ($3.4 million); the Wack-Wack property in Mandaluyong City in 2011 for P127 million ($2.7 million); Hans Menzi Compound in Baguio City in 2012 for P93 million ($2 million); Banaue Inn compound in 2012 for P10 million ($200,000); Mapalad property in Paranaque City in 2013 for P247 million ($5 million); and the J. Y. Campos property in Baguio City in 2014 for P160 million ($3.4 million).

Banana magnate, too

In 1987, banana magnate Antonio Floirendo entered into a compromise deal with the PCGG and turned over P70 million ($1.5 million) in cash and assets. The Marcos assets he gave to the PCGG included the Lindenmere Estate and Olympic Towers in New York and the real property listed as 2443 Makiki Heights Drive, Honolulu, Hawaii.

The PCGG sold the Marcos assets under Floirendo’s name such as: Beverly Hills property in California in 1994 for $2.52 million and its residual items for $42,300; the Makiki property in 1995 for $1.35 million; and the Lindenmere Estate in 1996 for $40 million. Since the Lindenmere property was heavily mortgaged, the PCGG’s share was $1.62 million.

Philippine Ambassador to Japan Roberto Benedicto, the dictator’s close friend since their law school days at the University of the Philippines, followed suit in 1990. In a compromise agreement with the PCGG, he surrendered $16 million in Swiss bank deposits, shareholdings in 32 corporations, 100 percent of the California Overseas Bank shares, and 51 percent of his agricultural lands, and cash dividends in his firms.

The PCGG sold the Marcos assets under Benedicto’s name, which two pieces of Intercontinental Broadcasting Corporation property in Cebu in 2001 for a total P228.5 million ($4.8 million), received P58.3 million ($1.2 million) as its share of just compensation of 40 percent of the proceeds of the 2003 sale of three tracts of sugarland in Negros Occidental, and privatized in 2008 the Eastern Telecommunications, Phils., Inc. shareholdings for P104 million ($2.2 million).

The PCGG recovered illicit assets from persons, who were not necessarily cronies but lesser known caretakers to whom Marcos entrusted his ill-gotten wealth. When the volume of his illegal operations grew at the height of martial rule, Marcos recruited unknown persons to do the job for him.

The PCGG entered into compromise settlements with low profile Anthony Lee, who surrendered shareholdings in Mountainview Real Estate Corporation in 1991; Alejo Ganut Jr., who surrendered P50 million ($1 million) in 1996; and Antonio Martel, who ceded a 4.6 hectare property in Bacolod City in 1996.

Crony Herminio Disini, who worked as agent for the sale of the ill-fated but overpriced Bataan nuclear plant, refused to cooperate with state authorities. After lengthy court battles, the PCGG secured from the Supreme Court in 2012 a decision declaring as ill-gotten the $50.56 million commission he received from Westinghouse,Inc., the supposed contractor of the Bataan nuclear plant.

The SC ordered the Vienna-based Disini to return the entire amount plus interest charges to the Philippine government. Disini has yet to respond to the SC decision.

Eyeing big companies

What the entire world knows after 30 years is a mere fraction, and not the entirety, of the Marcos loot. A number of their illegally acquired assets in the country have been identified.

What has been stashed abroad remains a big question, although it has been estimated that the loot could be between $5 billion to $10 billion.

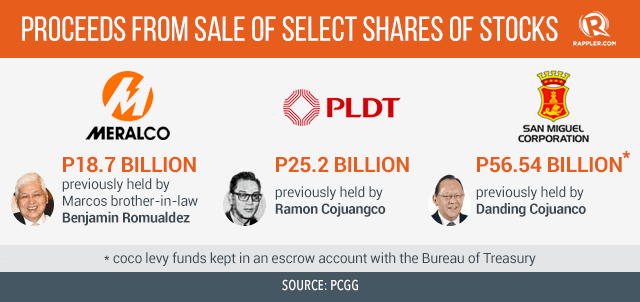

Marcos was not content to receive huge under-the-table commissions from foreign contractors of big ticket state projects. Marcos and his cronies had set their eyes, too, on major firms long regarded as blue chips by the stock market. These included Manila Electric Company (Meralco), Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company (PLDT), and San Miguel Corporation.

Marcos, using brother-in-law Benjamin Romualdez, took control of Meralco and sent its owners, the Lopezes, to exile in the US shortly after he declared martial law in 1972. Marcos secretly used Ramon Cojuangco as his nominee in PLDT. Marcos used crony Eduardo “Danding” Cojuangco Jr to use coconut levy funds and take control of SMC.

The PCGG did not lose time in filing claims on blocks of shareholdings believed to be owned by the Marcoses and their ilk in those three firms. The judicial grind was taxing to the spirit, but after years of court litigation they bore fruit as the government had recovered billions of pesos from the sale of the contested shareholdings.

The PCGG recovered and sold to the private sector the first batch of Meralco shares held by Benjamin Romualdez in 1994 for P13.5 billion ($280 million); the second batch in 1997 for P2.6 billion ($55 million); the third batch in 1998 for P53 million ($1.1 million); and the fourth and last batch in 2008 for P2.1 billion ($44 million), or a total of P18.7 billion ($393 million).

The recovery of the Marcos assets in PLDT took a more circuitous route. The court litigation was characterized by earlier decisions only to be overturned by motions for reconsideration. In the end, the PCGG has secured in 2006 the final decision from the Supreme Court saying that the contested shares belonged to Marcos and not to the family of Ramon Cojuangco.

In 2006, the PCGG sold to the Metro Pacific Holdings., a local firm owned by the Hong-Kong based First Pacific Group, the PLDT shares worth P25.2 billion ($530 million), ending 20 years of court battle.

The PCGG’s claim over the Marcos assets in SMC is largely a function of the collection of coconut levy funds from coconut farmers. The coco levy originated in the 1970s when Marcos decided to tax coconut farmers, promising them the funds would be used to develop the coconut industry and they would represent their investments.

Cojuangco was the main beneficiary of the funds in his capacity as SMC chair. A huge part of the coconut levy funds were used to buy the United Coconut Planters Bank (UCPB). Later, UPCB was used by Cojuangco to acquire the controlling interest in SMC.

The Supreme Court ruled in 2011 that Cojuangco’s 24 percent stake in SMC was not part of the coco levy funds. Neither did it belong to the Philippine government. The SC ruling also said that the government failed to prove that Cojuangco was a Marcos crony.

But in 2012, the Supreme Court reversed its earlier decision and ruled that the questioned assets came from coconut levy funds. It ruled with finality that the government owned the 24 percent block of shareholdings and that they should accrue for the benefit of the coconut industry and coconut farmers.

The PCGG acted to redeem the SMC shares and placed the sales proceeds of P56.54 billion (nearly $1.2 billion) in an escrow account with the Bureau of Treasury. Moreover, it filed a motion with the Supreme Court to deliver another 4 percent SMC shares worth P14.12 billion (around $300 million), which represented the amount that accrued to the government’s shareholdings had they not been converted into treasury shares.

Fake names in Swiss banks

Beyond raiding companies and using dummies, the Marcoses also put huge sums in foreign banks.

No one knew the exact magnitude of the secret bank deposits of the Marcoses and cronies in Switzerland and other tax havens, which serve as destinations for the illegal wealth. This remains a Gordian knot in the quest for the illicit wealth of the dictator and cronies.

While fleeing from Malacañang on the fateful night of February 25, 1986, Marcos failed to get rid of many documents, which showed he owned secret bank deposits in Switzerland and Liechtenstein. They were listed under a dozen foundations.

Ferdinand and Imelda used the fictitious names “William Saunders” and “Jane Ryan,” respectively. Among the recovered documents were “declaration/specimen signatures” forms that the couple signed with their real names as well as pseudonyms.

The discovery prompted the newly installed Aquino government to work for the freezing, recovery, and repatriation of those secret Swiss bank deposits. But the circuitous litigation in Swiss courts and domestic courts took years. It was only in 1995, or after close to a decade, that the Swiss courts ordered the transfer of those Swiss bank deposits, although the return depended on the final ruling of the local courts on its disposition.

In 2000, the Sandiganbayan ordered the forfeiture in favor of the government of the secret Swiss bank deposits of $658 million, which grew to that level after the discovery of more secret banks. In 2003, the court ruled in favor of the PCGG in forfeiting in favor of the government the Swiss deposits.

The decision paved the way for the submission the following year of the recovered money in the Bureau of Treasury.

On the positive side, the saga of the hidden wealth of the Marcoses and cronies in Switzerland has triggered policy changes in the Swiss banking system, affecting huge bank deposits suspected to have been earned by fraud and other illegal means.

In 1995, the Swiss Parliament enacted an amendment to an existing law that effectively removes legal impediments to the repatriation of illegal wealth to the host country. Swiss laws no longer require the final judgment on the criminal conviction of the depositors, who face court charges for their illegal acquisition.

Sustaining this law, the Swiss Supreme Court promulgated in 1996 a landmark decision that criminal proceedings are no longer required for their repatriation. Hence, civil or administrative proceedings would be enough. The ruling also gave deference to the final judgment of the Philippine court as to the ownership of these deposits.

The changes in the legal environment were to be expected. The global reputation of Switzerland and its banking system was at stake, as its banks were perceived a haven for money laundering, specifically those obtained by crime.

Tasks ahead

Fast forward to 2016.

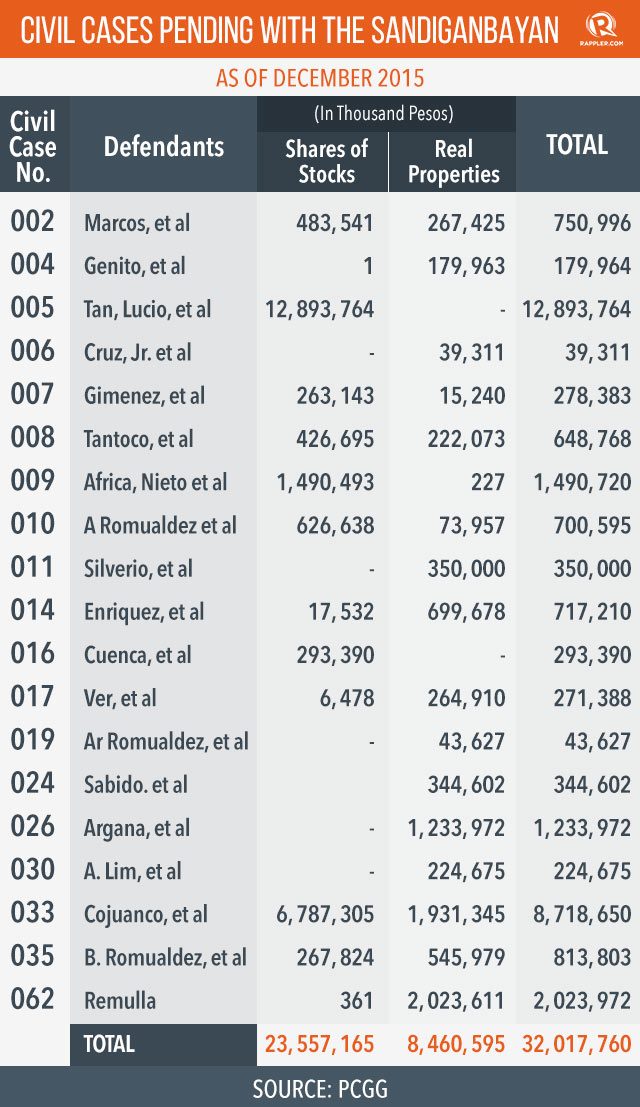

PCGG chair Richard Amurao, whom President Benigno Aquino appointed in 2014 to replace Andres Bautista, now Comelec chairman, is working on the recovery of illegal assets worth P32 billion ($673 million) before the Sandiganbayan. Civil cases against 19 parties have been pending with the anti-graft court over the past one or two decades.

The civil cases involve the P12.9 billion ($271 million) worth of shareholdings listed under Lucio Tan’s name, P6.8 billion ($143 million) shareholdings listed under Eduardo Cojuangco, Jr’s, and P1.5 billion ($32 million) shareholdings listed under the squabbling pair of Victor Nieto and Manuel Nieto’s.

The other civil cases are the claims on P483.5 million ($10 million) worth of shareholdings and P267.4 million ($5.6 million) worth of real estate property of the Marcoses; P626.6 million ($13 million) worth of shareholdings; P73.9 million ($1.6 million) worth of real estate property listed under Alfredo Romualdez’s name; and P426.7 million ($9 million) worth of shareholdings and P222.1 million ($4.7 million) worth of real estate property listed under the Tantoco couple – Bienvenido and Gliceria.

Amurao said that P78 billion ($1.6 billion), or almost 40 percent of the recovered assets of P170 billion ($3.6 billion), went to the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP), which the Cory Aquino government launched in 1987. The money was used mainly for land acquisitions and post-acquisition services to enhance the farmers’ productivity.

Amurao, however, could not categorically say when the PCGG should terminate its affairs, although he has expressed belief that it has to wait for the conclusion of the remaining civil cases. – Rappler.com

* $1 = P47.58

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.