SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Elders say you shouldn’t make promises you can’t keep. In the run-up to the 2022 elections, the media-elusive Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. snubbed debates, avoided specific questions on platforms, and mainly stuck to his message of unity.

Unity was his motherhood statement, but it’s one that, for better or for worse, captured the imagination of the Filipino public. It was also his most striking – if not, only – campaign promise.

Two years into his presidency, even that, he may have failed to keep.

Marcos Jr., son of the late dictator, is entering his third year in office with the threat of political instability looming over his shoulder, in the form of Vice President Sara Duterte, his 2022 running mate and now-resigned Cabinet member. The duo, scions of major political families, forged a formidable alliance more than two years ago, one that was too high-maintenance to keep until it could no longer be saved.

His third year in office is now shaping up to be a challenging political road for the President, who has been consolidating his allies to ensure success in the midterms, a vote that will be seen either as an affirmation or rejection of his administration’s policy direction.

A breakup to remember

Analysts point to numerous clues that spelled the end for the so-called Uniteam, but no bigger single-day spectacle could match the January 28 showdown rallies in Manila and Davao between the two families.

Held in the Philippine capital was the so-called Bagong Pilipinas (literally new Philippines) concert, a multimillion-peso event mounted by Malacañang to formally launch the administration’s supposed new brand of leadership. It was, as critics put it, a PR blitz that remains the subject of criticism up to this day, and was reminiscent of how Bongbong’s father, Ferdinand E. Marcos, resorted to buzzwords to keep the façade of good governance during the dictatorship years.

The Dutertes matched that concert in Manila with their own rally in their hometown, attended not only by their most loyal supporters but also by former allies of the incumbent administration. The event sought to protest the government’s charter change agenda, but it also became an avenue for Rodrigo “Digong” Duterte to engage his successor in a bitter word war.

It has been a downward spiral since then. Months later, First Lady Liza Araneta Marcos would publicly admit her ill-feelings towards the Vice President, who allegedly laughed during that Davao City rally when her father accused the President of taking illegal drugs.

Other signs painted a picture of a tumultuous situation within the administration – the Vice President’s public opposition to the revival of peace talks, her rift with House Speaker Martin Romualdez, and the removal of confidential funds from her office, among others.

Just a week before the Marcos administration turned two, Sara Duterte put the final nail in the coffin of their alliance by resigning as deputy of the country’s anti-communist task force, and secretary of education.

“Marcos won based on the framework of Uniteam even if it was just a hot air balloon, so it is important for him to pay lip service to the Uniteam. It wasn’t a simple win, it was a historic win because 61% of voters picked him,” former presidential political adviser Ronald Llamas told Rappler.

“He wanted to maintain that status semblance to manage that,” he added. “But now, he can no longer manage it.”

Undoing a Duterte

In Philippine politics, the dissolution of a marriage of convenience like that of Bongbong and Sara was not difficult to imagine. In fact, many had boldly predicted it even before the two officials took their oaths of office.

The two families – dynasties in their bailiwicks – go way, way back, but the Dutertes’ relationship with Marcos Jr. is remarkably fragile. Insiders say Bongbong and Sara didn’t really have a solid foundation of friendship to begin with before they ran as a tandem. The Duterte patriarch, meanwhile, admired the senior Marcos, but not the son, whom he called “weak.”

It was also, however, not far-fetched to assume that Bongbong would become a continuity president, having run his campaign alongside allies of the Dutertes. Raised by an authoritarian, Bongbong could have also had a worldview that aligned with his predecessor’s leadership style.

But once Marcos Jr. took helm of Malacañang, he gradually distanced himself from what made the old man from Davao a pariah in the international arena.

The latter set a very low bar on human rights, it didn’t take long for Marcos to overcome it.

Drug war deaths under Duterte neared 20,000 in his first two years only, based on human rights groups’ tally; the number was down to under 400 after Marcos’ first year as president. Duterte touted a shoot-to-kill rhetoric; Marcos said he is against addressing the drug menace by confrontation and violence.

Duterte coddled Apollo Quiboloy; now that Marcos is president, the fugitive doomsday preacher is in hiding and could not get special treatment.

Duterte persecuted former senator Leila de Lima and journalist Maria Ressa, who were among his staunchest critics; under Marcos, charges are slowly being dropped against them, and De Lima is completely free.

“Under BBM, we are given the opportunity to make use of a democratic space in transition from the authoritarian regime that was Duterte’s,” De Lima said in February.

Duterte’s government nurtured an environment that allowed Philippine offshore gaming operators to thrive; Marcos’ anti-crime body in Malacañang has doubled down on its crackdown on POGO hubs.

Duterte fostered closer ties with Beijing and set aside an important arbitral ruling on the West Philippine Sea; Marcos has toughened the line on China and clung to the Philippines’ Hague victory.

Comparisons to Aquino

It’s a funny irony that Marcos would share similarities with former president Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III. While both hail from the ruling elite, their fathers were rivals in Philippine history, with one being accused of orchestrating the assassination of the other.

But Marcos’ second year in office was accentuated by their parallels. Like his late predecessor, Marcos showed a certain resolve in asserting Manila’s claims in the West Philippine Sea, and tried to rally nations in support of the Philippines against China’s expansive claims in the disputed waters.

“I don’t see it. I don’t see it at all, because, well, I just don’t see it,” Marcos said emphatically, when asked about the comparisons to Aquino during an interview with Philippine media in Washington in April.

His pivot from China towards the US has made him a new rockstar of sorts on the global stage, despite sporadic and embarrassing reminders about his family’s history of excesses. He secured prestigious speaking engagements, delivering high-profile speeches before the Australian parliament and the premier defense forum Shangri-La Dialogue, where he was introduced as “one of Asia’s most dynamic leaders.”

“The Philippines will not give a single square inch of our territory to any foreign power,” Marcos would say, over and over, as tensions in the West Philippine Sea took a turn for the worse.

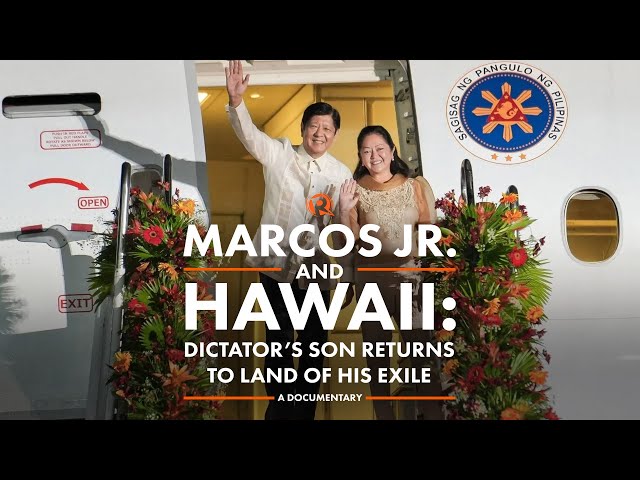

Marcos got to visit the US four times since he became president, something he could not do in the past due to the risk of arrest in connection with his father’s Martial Law sins.

He was able to return to Hawaii, the land of his exile, in November as a seemingly triumphant man with the power of reframing the years surrounding his family’s downfall in 1986. “We landed here with nothing,” he said, even though all the jewelry they brought to the island would say otherwise if only they could talk.

In his last trip to Washington, he rubbed elbows with Japan’s Fumio Kishida and US President Joe Biden, in a landmark trilateral summit that sought to address their mutual China problem.

He became the new poster boy for international rules-based order, and was included in TIME Magazine’s annual list of the world’s most influential people.

“Bongbong has stood steadfast against Chinese aggression in the disputed South China Sea and bolstered his nation’s alliance with the US,” the publication wrote. “By trying to repair his family name, Bongbong may reshape his country too.”

Pressing issues at home

Whether or not defending Philippine territories against foreign power would become a campaign issue in 2025 remains to be seen, although some surveys have shown that the West Philippine Sea is a lesser priority for Filipinos than economic concerns, such as arresting inflation, creating more jobs, increasing workers’ salaries, and reducing poverty.

The Marcos government has packaged his constant travels – for which his office had a billion-peso budget this year – as a means to woo foreign investors to the country, but it’s uncertain how the public resonates with that justification.

While he continues to have majority support, Marcos has seen his approval score tumble, based on Pulse Asia’s most recent numbers. Sara faces a similar predicament – an indication that she’s not as invincible as her populist father – although she continues to be the country’s most trusted in government.

In that same survey, Marcos’ trust rating saw its biggest drop in Mindanao – a whopping 32-percentage points – while Sara’s numbers remained steady in the region.

Managing the Dutertes, just like how it has been in the last two years, continues to be a recurring theme – or headache – of the Marcos presidency, casting a long shadow on elections that are decided not only by how effective aspirants are in presenting themselves as the solution to the country’s most pressing problems, but also by how they counter their opponents.

The Dutertes are a wildcard for the 2025 midterms. If Sara were to be believed, her father and her two siblings will all gun for the Senate at the same time, a scenario that puts into question who will be left in their hometown to take charge of the city hall that they haven’t given up in more than two decades. There are a lot of ways to position themselves – as underdogs, especially in the face of Duterte’s potential arrest by the ICC for his anti-drug campaign; as the bullied, in light of budget cuts for Representative Paolo Duterte and Vice President Sara’s offices; as the new opposition, to maintain their relevance on the national stage.

Sara’s regional party Hugpong ng Pagbabago, which was part of the 2022 Uniteam alliance, is unlikely to be part of the 2025 coalition that the Marcos administration is building. His political vehicle, the young Partido Federal, has been coalescing with older, more established parties composed of the same, old dynasties in Philippine politics.

Opposition forces since 2016 have not fully established their plans for 2025, but the Liberal Party of the late president Aquino has not closed its doors to the idea of teaming up with Marcos’ party. It’s a possibility that would taint LP’s long anti-Marcos history, but one that could also strengthen the anti-Duterte network heading to 2025.

Such an option – which was unthinkable years ago – offers a chance for Marcos to reinvent the promise of unity he declared over and over during his campaign, in a “new Philippines” that he supposedly wants to achieve.

“Bagong Pilipinas is not a new partisan coalition in disguise,” he asserted in January. “Bagong Pilipinas serves no narrow political interest. It serves the people.” The President has yet to prove that these are more than just words.

If a presidency is defined by promises kept and promises broken, how can Marcos carve his legacy?

– with reports from Kaycee Valmonte/Rappler.com

This article is part of “Marcos Year 2: External Threats, Internal Risks,” a series of analyses and in-depth reports assessing the second full year of the Marcos administration (July 1, 2023, to June 30, 2024).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Rappler’s Best] Fasten seatbelt, Mr. President](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/fasten-seatbelt-mr-president-edit.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=235px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Power of mimicry: How human rights are covertly undermined in PH](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/duterte-marcos-human-rights.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Vantage Point] BBM Year 2: Hits and misses](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/thought-leaders-marcos-hits-and-misses.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=277px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Closer Look] ‘Join Marcos, avert Duterte’ and the danger of expediency](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/TL-trillanes-duterte-expediency-june-29-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.