SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

AT A GLANCE

- The Philippine government imposes a blanket ban on health workers due to a labor shortage amid the pandemic.

- The move angers thousands of nurses who are bound to leave the country to return to their jobs overseas.

- Days after, the Inter-Agency Task Force modified the ban to allow those who have contracts as of March 8.

Jerrick Gomez was on the last leg of a nearly 3-year process of trying to find work in the United Kingdom when he returned to the Philippines in the last week of February.

Jerrick did not think twice when he packed his bags and left Saudi Arabia, where he worked as a company nurse for 4 years after moving to the Gulf state in 2016. He had paid nearly P150,000 in exams and lost countless days of sleep traveling to Riyadh to meet application requirements.

On his way home, Jerrick thought only of his wife, Jhoanne, also a Filipino nurse, and whom he left in Saudi Arabia. His plan was clear: come back to the Philippines, submit his visa application, and leave as soon as possible for a new job as a home care nurse in Whitehaven, a town 5 hours north of London.

For Jerrick, a job in the UK would give him enough resources to start a family of his own. He and his wife got married in 2018 and a week after arriving in the Philippines, he found out she was pregnant with their first child.

At the time, all he had to do was to wait for his passport to be released so he could secure an overseas employment certificate and then board a flight to Britain.

Then the Philippine government implemented a sudden deployment ban, prohibiting health workers from leaving the country.

Up until that point, Jerrick had been motivated by his plan to work in the UK and support his family. After hearing about the new order, only worry filled his mind as he thought of his wife and baby left in Saudi Arabia.

Instead of looking forward to a new start, Jerrick now had a dilemma as he and his wife were both out of work – him, after leaving his job, and his wife, after finding out she was pregnant and deciding to stay home to avoid getting infected with the coronavirus.

“When I heard that, I just lost all hope,” Jerrick said in an interview with Rappler.

But Jerrick’s concerns were only one among the thousands of nurses and health workers who were left stranded by the Philippine Overseas Employment Agency’s (POEA) order.

The POEA’s ban, the agency said in an April 2 resolution, was put in place to “prioritize human resource allocation” in the country’s health care system during the coronavirus outbreak.

Filipino nurses who have been forced to leave the country after decades of fighting for higher wages and better working conditions did not buy the government’s explanations. Nurses took to social media to express their outrage, prompting Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin Jr to take notice and demand a review of the POEA’s order.

By April 13, the government’s coronavirus task force eased restrictions to allow health workers with existing contracts as of March 8 to leave the Philippines.

Cabinet Secretary Karlo Nograles, the spokesperson for the government’s coronavirus task force, described the compromise as a “win-win” solution resulting from a discussion on the country’s needs during the pandemic, as well as legal issues related to contracts and rights of Filipinos to work overseas.

But despite the quick turnaround of events, nurses say the government’s moves only expose once more the plight of Philippine health workers, whose voices have been ignored by several administrations.

Overworked, underpaid

Marj*, a UK-registered nurse, felt the government had no right to force her to stay in the country.

Like most nurses stranded in the Philippines, Marj was surprised by the POEA’s sudden deployment ban. She arrived in the Philippines early in March for a visit planned 8 months in advance and was supposed to leave on March 31.

Marj had been counting the days when she could fly home with a suitcase filled with souvenir shirts, keychains, and chocolates for her first visit back since starting work in London in 2019.

“We don’t just pick up money from the ground,” Marj said. “They cannot stop us from leaving because it is our right to leave.”

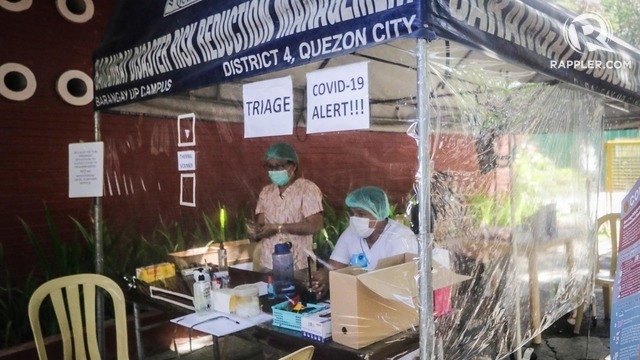

The POEA initially urged health workers affected by the ban to volunteer with the Department of Health (DOH) to treat coronavirus patients. Latest figures as of March 30, count 1,000 health workers who signed up for the DOH program.

Marj voiced the frustration of many nurses whose posts flooded the timelines of several Philippine nursing groups reacting to the government’s moves.

“I myself worked here in the Philippines before and volunteered for 6 months without pay. The government never appreciated nurses, you can’t blame them for wanting to go abroad. Nurses here are underpaid, overworked, under appreciated. Now they want our help?” she said.

Like Marj, Chiara Cruz endured years of volunteer work and a monthly pay of less than P10,000 as a nurse in the Philippines. Early 2019, she finally landed a job in a hospital in Exeter, a city 280 kilometers southwest of London. It’s a dream that came true, she said.

Chiara went home late February for a holiday, to mark her first year of work as a UK nurse. She was supposed to return to Exeter on March 28 but her flight was canceled because of the Luzon lockdown. Chiara rebooked her flight to April 23, using up her remaining leave credits for 2020.

Her vacation turned into a nightmare. She thought about using her leave credits for 2021 in advance, paying her rent in the UK, and the safety of her colleagues – Filipinos too – who would have to work double shifts to cover for her as she remained stranded.

“I used to earn P8,000 a month in the Philippines. Does the government really think poorly of us? Because of the pandemic, our lives are at stake here. It’s a life and death situation. The P500 daily allowance for volunteering is not worth the life of a person,” Chiara said.

The Philippine Nurses Association (PNA) said in a position paper on the POEA’s order that “requiring medical nurses to render service despite the fact that many have employment contracts is tantamount to involuntary servitude.”

PNA said there were no consultations done by the POEA or Department of Labor and Employment before the deployment ban was issued.

The DOH’s volunteer program initially drew flack for proposing to pay health workers P500 a day. Volunteers would have to serve for two weeks of duty, and another two weeks during quarantine, for a total of P14,000 pay for the month. Food, lodging, and transportation allowance would also be provided.

After a backlash, Health Undersecretary Maria Rosario Vergeire said the DOH was studying the prospects of increasing health workers’ pay.

Apart from that, volunteers are also supposed to receive a one-time special risk allowance, amounting to 25% of the pay, or P3,500. This is on top of a mandated hazard pay worth 25% of their monthly pay (another P3,500) under the Magna Carta for public health workers, if they are to serve public hospitals.

Volunteers will also be covered by the compensation package under Republic Act 11469 or the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act, which ordered the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation to shoulder all expenses in case they get infected with the virus. If their case becomes critical, they will be entitled to P100,000. In case of death, the volunteer’s family will receive P1 million in compensation.

‘We need them here’

POEA Governing Board Resolution No. 9 cited a shortage of 290,000 health workers in the country, as the primary reason for the ban. According to POEA Administrator Bernard Olalia, these figures came from the Human Resources for Health Network (HRHN), an inter-agency support network led by the DOH.

In 2019, HRHN raised concerns about the shortage, as the World Health Organization set the standard of 44.5 health workers for every 10,000 people, under the Sustainable Development Goals. That meant there should be 480,600 health workers for 108 million Filipinos.

Olalia added that the POEA acted on Section 4(m) of the Bayanihan Act which says the government should “engage” temporary health workers to complement the current workforce.

“We need a lot of frontliners now because of the pandemic. So instead of allowing our healthcare workers to go to other countries, and serve the pandemic problem there, we might as well tap them here,” Olalia told Rappler in an interview.

The POEA chief added they wanted to “prevent the greater risk” of health professionals getting infected by the coronavirus overseas. “We also would like to unburden the emotional stress of their families,” he said.

After the nurses’ uproar, the Inter-Agency Task Force (IATF) modified the ban – which, in Olalia’s view, “upheld” the POEA’s power to impose the restriction, save for an exception.

“DOH presented figures on the number of reserve nurses. According to the data provided by the Professional Regulation Commission, there are over 400,000 reserve nurses,” Olalia said.

Some members of the IATF, like Labor Secretary Silvestre Bello III, remained unconvinced of the supposed reserve workforce, Olalia recounted. Rappler reached out to Health Secretary Francisco Duque III for comment, but he has yet to respond as of posting.

“We don’t know where they are. Are they willing to work? What’s important is that there are findings of labor shortage. The reserve is not important,” Olalia said.

But because of the “big reserve,” the IATF allowed for the exception – those with contracts as of March 8 will be allowed to leave. This means that those who were unable to process their contracts a week before the Metro Manila lockdown on March 15 will have to stay.

In a task force media briefing on Tuesday, April 14, Nograles said the government’s final decision was a “balancing act.” “We all pitched in and aired our concerns and that was the consensus,” he said.

But the government’s decision left nurses with more questions than answers.

Jerrick, whose contract was signed on March 12, did not understand why the government set March 8 as a cutoff date. Jerrick asked the POEA for an answer, though he has yet to receive any word from the agency.

“When it was being deliberated, while I was there, it was supposed to be 12 March of 2020. So when the resolution came out, I don’t know why it became March 8. I don’t know the reason behind that March 8,” Olalia told Rappler. The President announced the Metro Manila lockdown on March 12.

For now, nurses like Jerrick remain in limbo.

‘Public service’

The ordeal which played out amid the outbreak only deepened the wounds felt by nurses. When the deployment ban was still in place, all 3 nurses said they would not volunteer for the government despite being stuck here.

While the government branded the call to head to the front lines as a service to the nation, nurses asked where the sense of patriotism and caring for health workers were during their decades of fighting for better working conditions.

“Patriotism? Usually those who say that aren’t nurses, those who’ve never experienced being exploited. We were never given a choice. The only hope here for nurses is to work abroad or in a call center. It’s hard to work as a nurse here – you need to have connections in government to enter a public hospital while private hospitals pay low,” Jerrick said.

“To be honest, if they treated us better before this virus, it would have been easy to answer the DOH’s call. But that’s not the case. They’ve neglected us for so long so of course we are angry,” he added.

To rub salt on the wound, the health workers affected by the deployment ban are not covered by the P10,000 cash aid from the government. Based on guidelines, this assistance only covers OFWs who experienced job displacement due to a lockdown in the receiving country, or those who were infected with the disease.

On April 13, President Rodrigo Duterte said while he was “okay” with new provisions, health workers should stay in the country to fight the pandemic as there was “no end in sight…and our numbers are increasing.”

He admitted the Philippines would not be able to match what other countries could offer them. Just a year earlier in 2019, the Duterte government blocked a petition in the Supreme Court seeking a hike in the salary grade of government nurses, saying it lacked legal basis and would result in inequity among government workers’ wages.

Despite this, nurses say that what they have fought for is more than politics. Jerrick, who’s worked as a nurse for over a decade, said past administrations have failed nurses.

“It’s like they’re only starting to appreciate us now. Did it really need a virus?” – Rappler.com

*Some interviewees requested the use of pseudonyms for their own privacy and protection.

Editors note: All quotations have been translated to English.

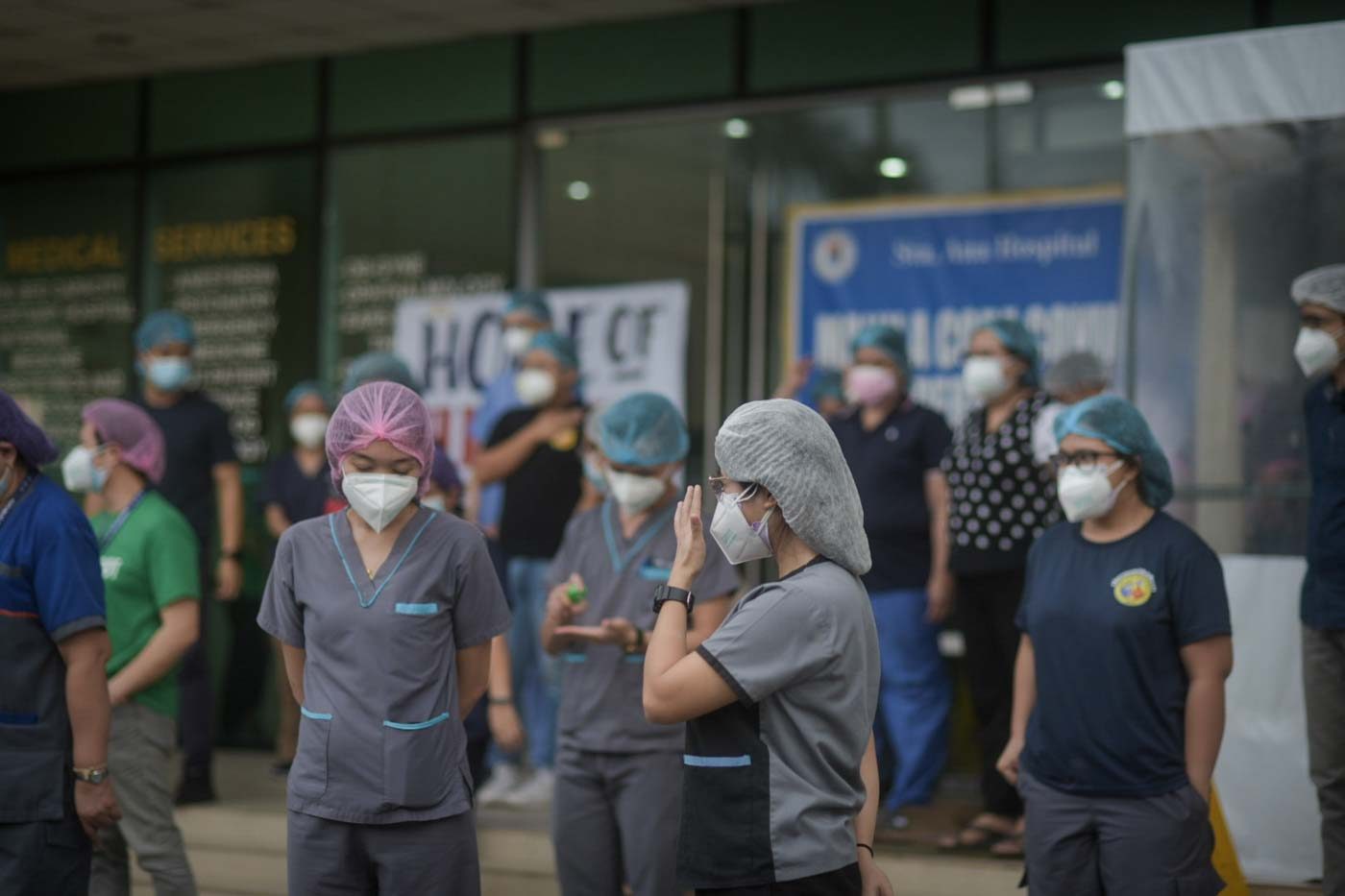

TOP PHOTO: FIGHTING A PANDEMIC. Medical workers take a moment to perform a solidarity clap for their fellow frontliners outside the doors of Santa Ana Hospital in Manila on April 9, 2020. Photo by Alecs Ongcal/Rappler

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Time Trowel] Evolution and the sneakiness of COVID](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-evolution-covid.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=455px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.