SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Filipinos are in misery, but why is Duterte slashing economic aid?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2020/08/economic-misery-August-28-2020.jpg)

Here’s where the economy is at, in case government officials need reminding.

We’re in the middle of the country’s first recession or sustained economic downturn in nearly 30 years. Economic losses totaled P707 billion from April to June. This means we produced considerably fewer goods and services compared with the same period last year.

This downturn is the biggest, most drastic since World War II. (READ: End of growth: How the pandemic ruined PH economy beyond recognition)

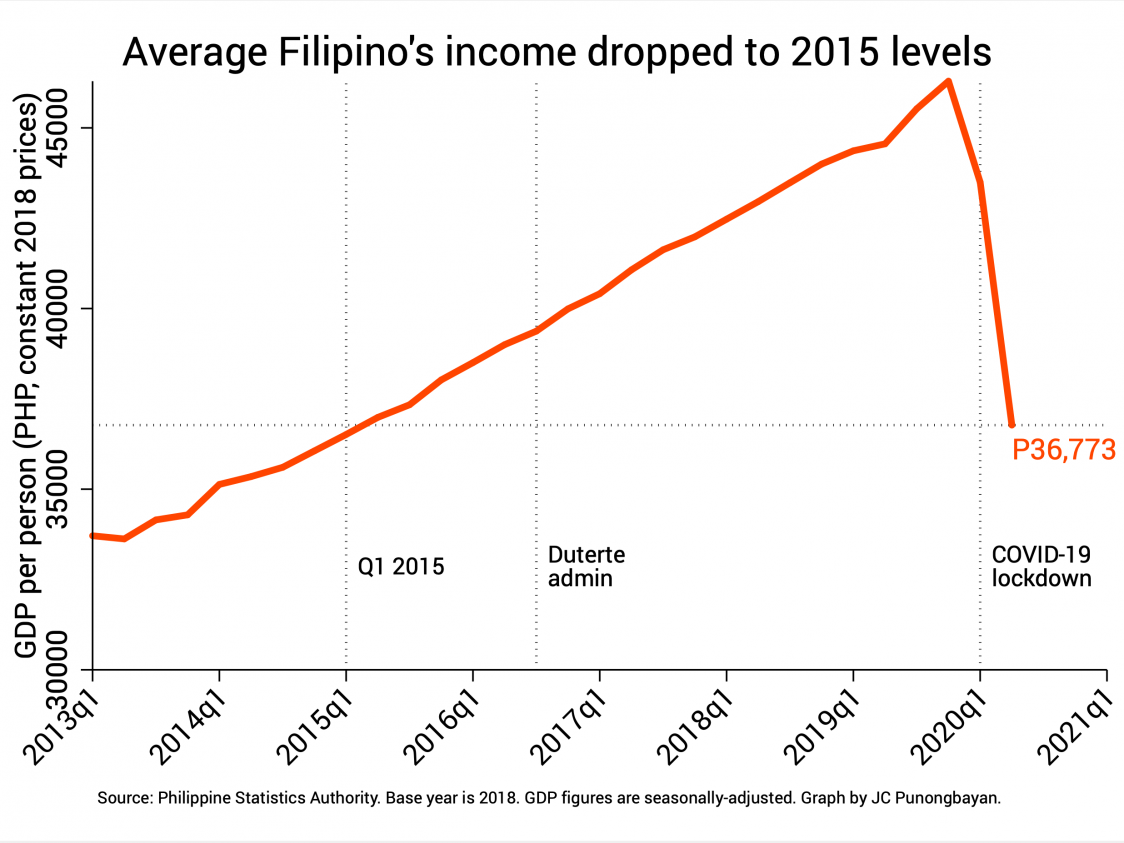

The decline in national income is so huge the each average Filipino’s share of the economic pie – otherwise known as gross domestic product (GDP) per person – dropped to its lowest level since 2015 (Figure 1).

Of course, GDP doesn’t capture everything that’s important, and doubtless many people will feel no worse off than they were last year, despite the pandemic and the recession.

Still, the vast majority of Filipinos will have seen a tremendous drop in their incomes. From the average Filipino’s viewpoint, it’s as if the economic gains of the past 5 years have been erased in one fell swoop.

Thousands of businesses have been forced to close down. As of June, 26% or about 1 in 4 businesses have stopped operations – whether permanently or temporarily – due to the pandemic.

Consequently, and unsurprisingly, millions of jobs have been wiped away.

From January to April the economy shed 8.9 million jobs (we’re waiting for the July jobs report out next week). The proportion of the underemployed – those who still have jobs but wanting more income or hours at work – has swelled to its highest level since 2016.

Joblessness – a concept related to but not strictly comparable with unemployment and underemployment – is also at a record high. According to the Social Weather Stations (SWS), nearly half of all adult workers surveyed said they were jobless.

Among them, overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) have been hit particularly hard. No less than 140,000 have been repatriated since May, and over 600,000 are seeking assistance from government.

OFW remittances, long considered the lifeblood of our economy, are shrinking by double-digit rates. This could prolong the economy’s contraction since a lot of Filipino households’ consumption spending is fueled by such remittances.

Meanwhile, one in 5 Filipino households experienced some form of hunger in July (also a record high) and as much as 5.5 million Filipinos might be pushed into poverty if they fail to receive enough aid.

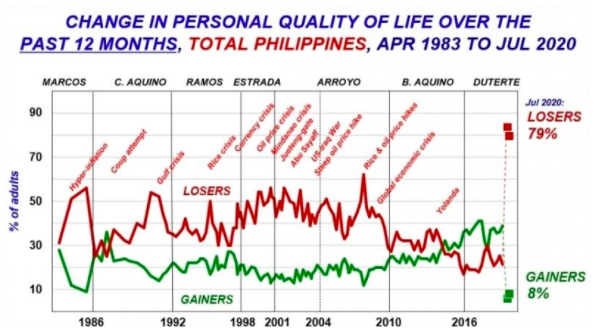

Pessimism on the economy has also skyrocketed. Nearly 8 in 10 Filipinos said the quality of their lives worsened over the past year (Figure 2). About 1 in 3 Filipinos foresee their lives worsening over the next year.

Where is the aid?

In short, all indicators point to a nation in extreme economic misery. Yet, alarmingly, enough aid doesn’t seem to be forthcoming.

For starters, the emergency subsidies authorized by the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act (aka Bayanihan 1) lasted for only two months, April and May. August is now drawing to a close, yet government still isn’t done handing out all of the aid for May. No future tranches are in sight.

The Bayanihan to Recover as One Act (aka Bayanihan 2) did allot P6 billion to supplement the programs of the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) for the rest of the year.

But that’s peanuts compared with the P200 billion cost of the emergency subsidies in April and May. Lots of poor households still haven’t received such aid, and lots more will need it as the economy further deteriorates.

At least 662,213 workers in the formal sector have benefitted from another program called the COVID-19 Adjustment Measures Program (CAMP).

But that P3.3 billion program involved a one-time payment of just P5,000. That’s below the monthly minimum wage in Metro Manila, and it doesn’t even cover workers in the informal sector where much of the poor belong.

In addition, too few people benefitted from CAMP considering there were 7.3 million unemployed Filipinos back in April. Many applicants have had to be turned down.

Aid for businesses has also been paltry.

The initial wave of financial assistance for micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) came in the form of the Department of Trade and Industry’s Pondo sa Pagbabago at Pag-asenso (P3).

But with just P1 billion at its disposal, funding dried up quickly and loan applications have been suspended. Many embattled firms failed to get help, leaving them with no choice but to close shop.

Other firms have received aid from the Small Business Wage Subsidy (SBWS) program, which has disbursed P41 billion so far. Wage subsidies are supposed to help businesses replace the lost incomes of their workers.

But each SBWS beneficiary is entitled to just two months of aid, and the payout for each worker is just P5,000 to P8,000 – also smaller than Metro Manila’s minimum wage and not nearly enough to feed and sustain a family of 5.

Bayanihan 2 does incorporate P55 billion for business loans, as well as P13 billion for cash-for-work programs. But these, too, are meager next to the total economic losses we’ve sustained so far. (READ: Bayanihan 2 is here, but it’s too small, too late)

Aid for some the most embattled sectors – tourism and transportation – has also been slashed.

Tourism stakeholders wished for at least P10 billion in aid, but Bayanihan 2 expressly allotted to them only P4 billion. Transportation stakeholders initially asked for P21 billion, but that went down to a mere P9.5 billion.

The glaring lack of aid was pointed out by Vice President Leni Robredo in a concise, no-nonsense address on Monday, August 24. Among other things, she called for additional rounds of emergency subsidies amounting to P5,000 for each poor household, good for 4 months, totaling about P200 billion.

But Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque rebuffed this proposal by saying government doesn’t have enough funds for it.

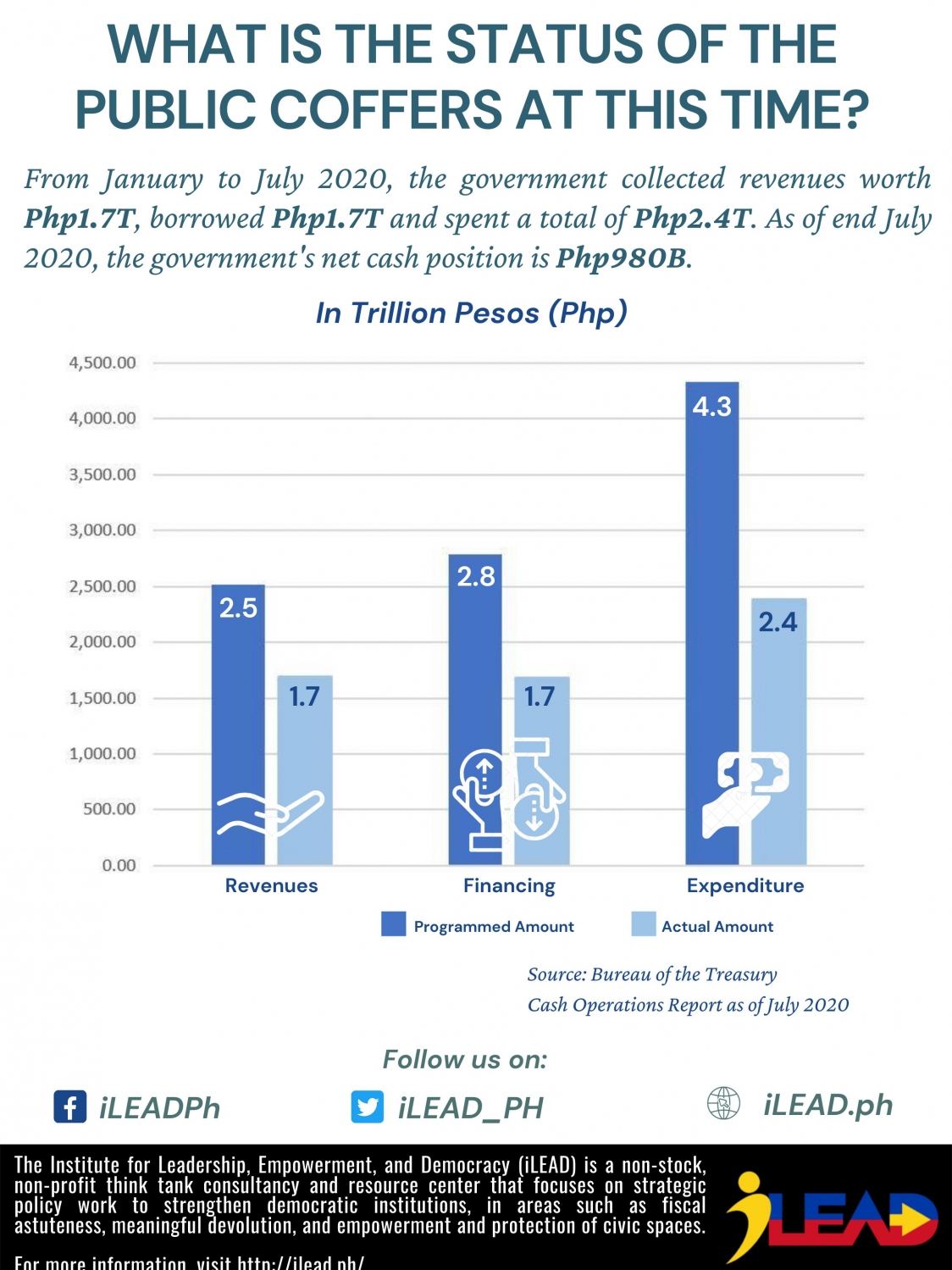

This is a lie. From January to July this year, government had P980 billion of funds in excess of what it has spent so far (Figure 3). Clearly, government has money.

Besides, if it so wishes, the Duterte government can always raise more money – even if it means incurring more debt. That’s a small price to pay compared to the large-scale and long-term loss of jobs and livelihoods sweeping the economy.

Unsettling 2021 budget

Perhaps most disturbingly, there’s little aid incorporated in the proposed 2021 budget as submitted to Congress by Budget Secretary Wendel Avisado this week.

Heck, the entire budget for the DSWD – supposedly at the frontlines of giving aid throughout this pandemic – was even halved!

My friends and I will write more on this next week. But apparently, policymakers are wedded to the notion that government can do away with considerable sums of aid because, anyway, things are expected to return to normal soon, and the economy can be safely opened up next year.

But this is delusional.

Even if a vaccine is discovered early next year, it will take many more months (even years) to manufacture and distribute enough vaccines to inoculate the vast majority of Filipinos.

Until then, it won’t be completely safe to revive the economy and bring it to full throttle. Millions will continue to be unemployed and will need help from government to pay for food, bills, and other necessities.

Rather than pour more money into aid, a huge chunk of the 2021 budget will go into infrastructure spending. But as analysts have said time and time again, this is infeasible. (READ: Why we can’t Build, Build, Build our way out of this pandemic)

By a string of misguided, dangerous assumptions, the Duterte government risks giving too little economic aid for Filipinos in the coming months and years.

In other words, far from abating Filipinos’ collective economic misery, government officials will likely deepen and prolong it. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate and teaching fellow at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Time Trowel] Evolution and the sneakiness of COVID](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-evolution-covid.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=455px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.