SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] The economics of Metro Manila’s burgeoning water crisis](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/930B207E96034672B7DC4899405B380F/img/EE19AE54266D4270ACA6FC1F59B71941/The-economics-of-Metro-Manilas-burgeoning-water-crisis-March-13-2019.jpg)

The water crisis seems to have crept up on all of us. But it really shouldn’t have.

Since last week, thousands of households in Metro Manila have been reeling from intermittent to zero water supply.

Without sufficient warning, Manila Water cut the water supply in at least 6 cities in Metro Manila and 7 towns in nearby Rizal province.

In many instances, the problem goes way beyond mere inconvenience. Some people have reportedly stopped going to work or sending their kids to school entirely because they haven’t had water for almost a week. In many places such as hospitals, the water shortage could easily result in life-threatening scenes.

Note, too, that summer hasn’t even been declared by the weather bureau. Until the rains come back, many fear this burgeoning water crisis could last for some time.

In this article let’s trace the roots of this water crisis and outline possible ways out of it.

Lower supply, higher demand

At the heart of this water crisis lies the basic issue of supply and demand.

Picture in your mind a bathtub. To empty it of water quickly, you need only close the faucet and keep the drain open.

This is essentially what’s happening to the two main reservoirs watering Metro Manila, namely Angat and La Mesa.

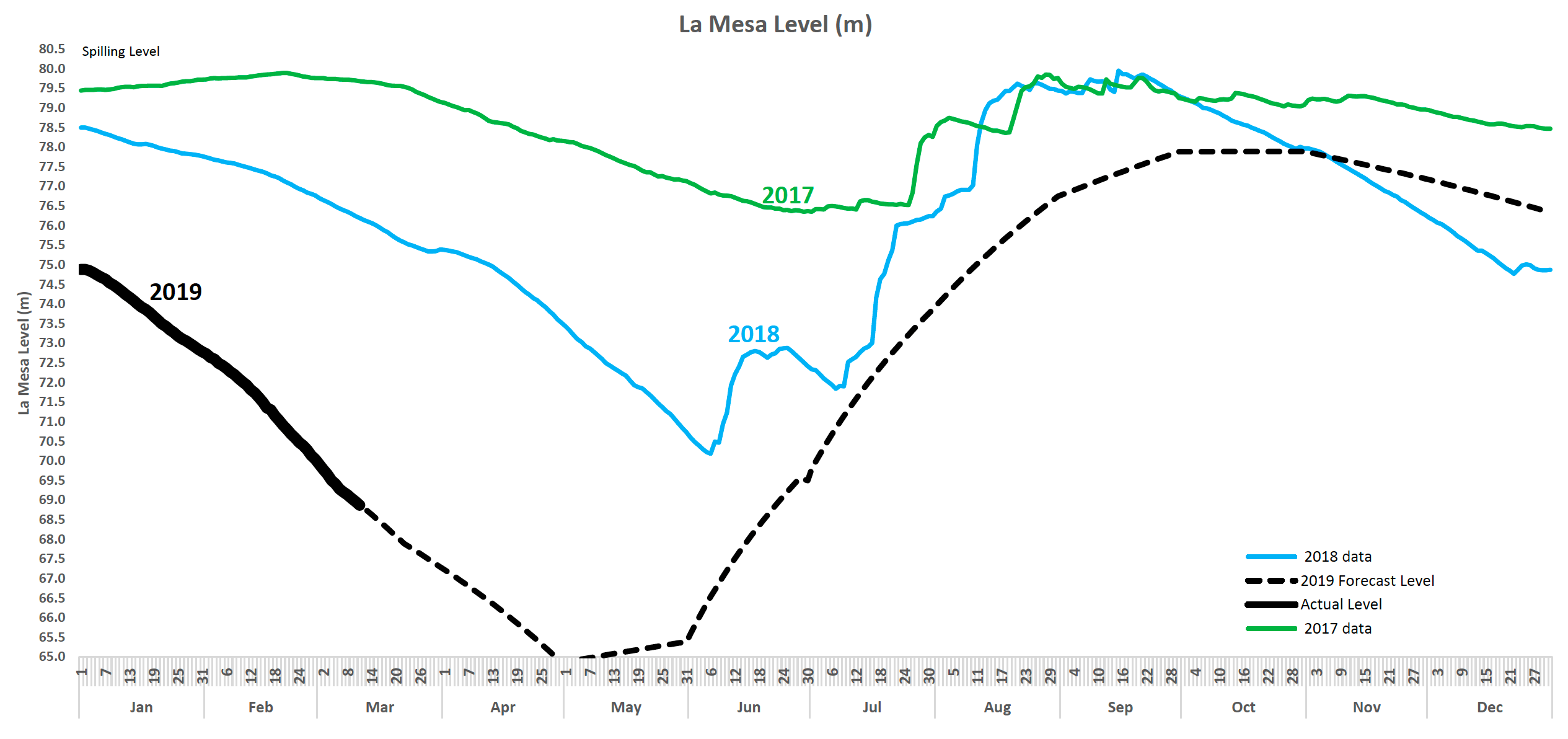

The water level at La Mesa is now at a 12-year low. Figure 1 shows that although the water level typically drops at the beginning of each year, the dip for 2019 has been particularly steep and has yet to reach its projected trough sometime in May.

Note as well that, since 2017, we’ve been starting each year with progressively less water supply in La Mesa Dam than the year before.

Figure 1. Source: Manila Water.

Figure 1. Source: Manila Water.

One factor to blame is the El Niño spell, which weather bureau PAGASA warned would be “full-blown” this year.

But this can’t be the whole story since the water level at Angat – from which Metro Manila sources virtually all of its water supply – is still safely above the critical level.

An official of PAGASA said in Filipino, “If it were El Niño, all dam levels should have dipped as well, but that’s not the case.”

Other than supply, we also need to look at demand: Manila Water admitted they have had to draw water from La Mesa Dam in order to keep up with ever-higher demand from its customers.

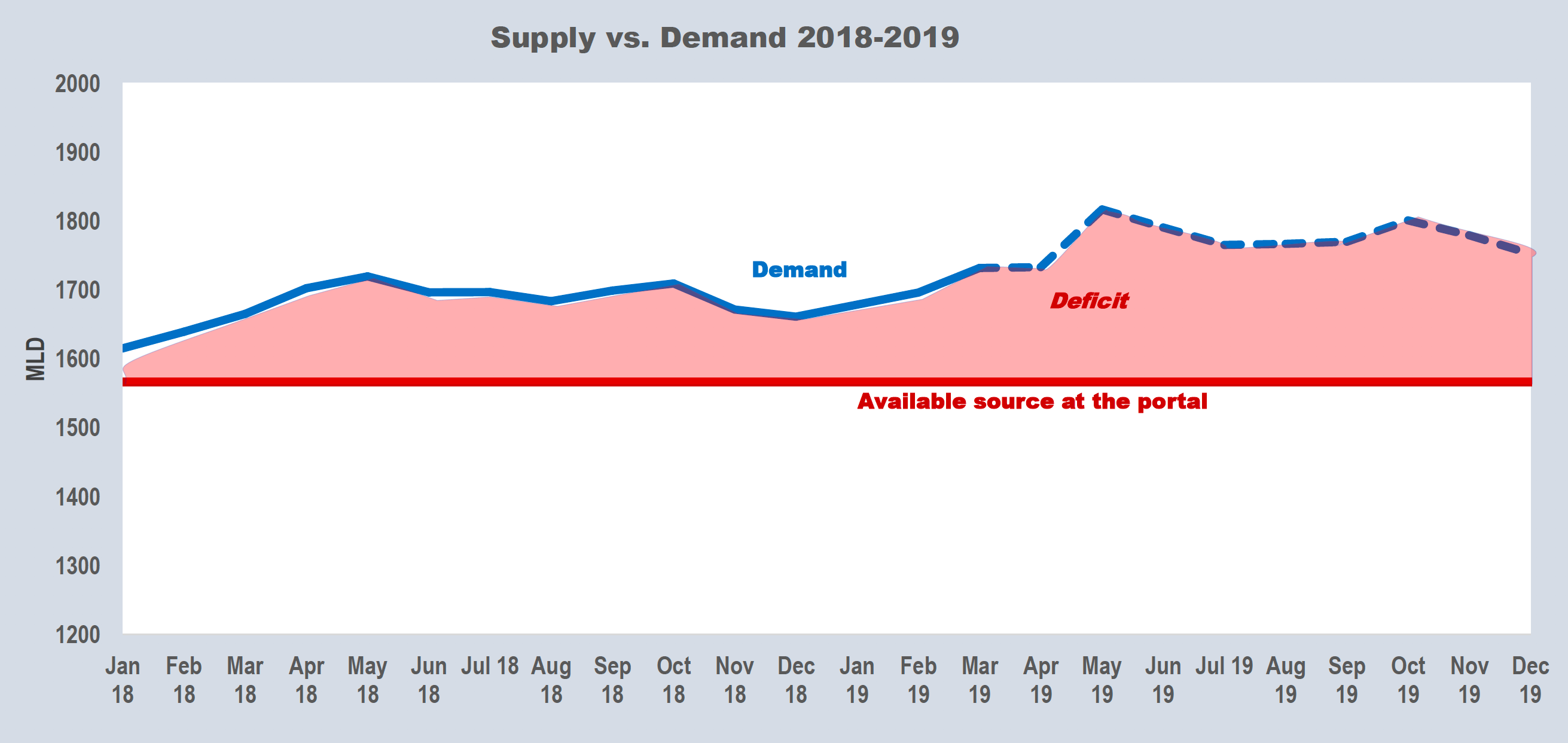

Every day, Manila Water can only get 1,600 million liters per day (MLD) from Angat Dam. Yet data show that demand among their customers now reaches as much as 1,750 MLD (or 9% higher).

Figure 2 below shows that since last year the demand faced by Manila Water has been outstripping its fixed supply. Worse, the water shortage is only projected to swell even more in the coming months.

Figure 2. Source: Manila Water

Deeper waters

The water crisis betrays the relative states of readiness between Manila Water and Maynilad, which serve the East and West Zones of Metro Manila, respectively.

While both draw water primarily from Angat, a majority or 60% of the total allocation goes to Maynilad and only 40% goes to Manila Water. Herein lies one advantage for Maynilad.

At the same time, whereas Manila Water only draws from Angat Dam for its water needs, Maynilad has alternative sources like smaller reservoirs, deep wells, and nearby Laguna Lake, having been able to expand their water infrastructure in recent years. Herein lies another advantage for Maynilad.

Manila Water, to be fair, already put forward its proposed Laguna Lake project to augment its supplies. But government via the MWSS turned this down for being “too expensive.”

Hence, by all indications, Manila Water is now in “deeper waters” than Maynilad (the irony is hard to miss).

Maynilad has already agreed to share part of its water allocation to Manila Water to abate the latter’s choking supply constraints. Manila Water, meanwhile, is also looking to rotate supplies and adjust water pressure across its network of pipes.

But beyond these quick fixes, we must look at the long-term solutions just as urgently.

Long-term solutions

First, we need to diversify our water sources and reduce Metro Manila’s singular reliance on Angat.

To this end, talks are reportedly underway between Manila Water (Ayala-owned) and Enrique Razon Jr. for the new and improved Wawa Dam in Montalban, Rizal. But a legal gridlock is currently hampering this project.

Meanwhile, one of the flagship projects under President Duterte’s Build, Build, Build is the New Centennial Water Source-Kaliwa Dam project, which is expected to supply an additional 600 MLD of water daily to Metro Manila once completed in 2023.

It is this project that the MWSS favored over the Laguna Lake project put forward by Manila Water despite warnings it could prove more expensive and already too late to avert an impending water crisis.

More significantly, this P12.2-billion project is funded by a Chinese loan requiring that the dam be built by a Chinese contractor, which eventually turned out to be China Energy Engineering Corporation (CEEC).

This loan also reportedly entails an interest rate of 2%, which is 8 times higher than the usual interest rate charged by Japanese loans.

Various groups are also opposing the construction of this dam since it could displace more than a thousand families (mostly indigenous people) and will likely disrupt the local ecosystem and biodiversity in Sierra Madre.

Aside from simply having more water sources, we may also need to take seriously (and fold into the mainstream) so-called “green infrastructure.”

Instead of insisting to build more “grey infrastructure” projects – like your typical dam, reservoir, or treatment plant – many countries are now looking into green infrastructure that deliberately takes into account (and makes use of) the environment’s natural water management systems.

Finally, we have to take anthropogenic climate change more seriously insofar as it generates more frequent extreme weather events that pose a direct threat to our already susceptible water supplies.

Real crisis

We’ve taken for granted the structural problems of our water sector for too long. It’s high time we changed that.

Maybe we can start by raising water as a top political issue in the May 2019 elections and beyond.

Rather than sing and dance, the senatorial aspirants will do well to spend their time to explain to the public how they plan to prevent a catastrophic water crisis so many people have been warning about.

Finally, the Duterte administration will do well to divert their energy and time from manufactured crises (like the country’s drug problem) to real crises (like Metro Manila’s water shortage).

But can we rely on them to recognize a real crisis if it was staring them in the face? – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.