SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[In This Economy] PISA 2022: Nowhere to go but up?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/12/PISA-Nowhere-to-go-but-up-December-8-2023.jpg)

Four years ago, I wrote a piece about the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), and how the Philippines fared in it. That was the first time our country ever joined PISA.

The results were dismal. Of the 79 participating countries, the Philippines ranked dead last in reading, and second to last in math and science.

Fast-forward to December 5, 2023, PISA announced their results for 2022. This time 81 countries participated, and a total of 7,193 Filipino students were assessed.

As one would expect, the results are not so encouraging.

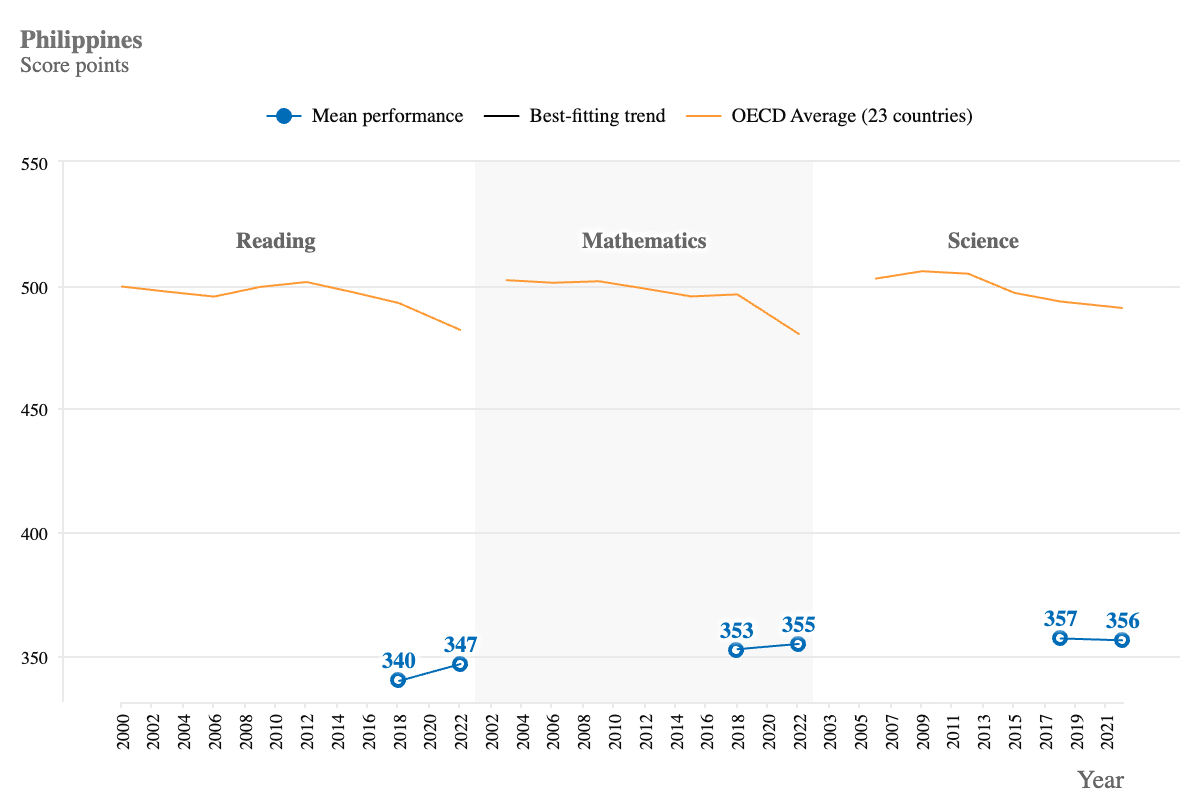

Sure, the Philippines’ scores rose marginally for reading (340 to 347) and math (353 to 355). But the score for science dropped (357 to 356). And none of these changes was statistically significant.

We bucked the global trend which saw a severe decline in mean scores owing to the pandemic (see Figure 1). But still, our performance was stagnant.

Figure 1.

What about our global rankings?

In math we ranked 6th to last, beating Guatemala, El Salvador, Dominican Republic, Paraguay, and Cambodia. But five of these other countries joined PISA for the first time in 2022, and the Dominican Republic was already dead last in 2018. Our math score was at par with Panama and Kosovo.

Meanwhile, in reading, we were 5th from last (at par with Dominican Republic, Palestinian Authority, Kosovo, Jordan, and Morocco). In science, we were 3rd from last (at par with Dominican Republic, Kosovo, and Uzbekistan).

We weren’t technically last in anything, but we still ended up among the poorest-performing countries. Kulelat pa rin. We seem to have bottomed out, and there’s nowhere else to go but up.

What about our neighbors? Singapore ranked first in all 3 subjects. Neighboring Macau, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Japan, and South Korea are not far behind. Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia all outperformed us. Vietnam even ranked higher than the US in math!

Unsurprising

No one should be surprised that we continue to perform poorly in PISA.

In fact, given the horrendously long lockdowns and school closures during the pandemic, as well as the learning gap between rich and poor students, it was reasonable to expect even worse outcomes than what we saw.

Notwithstanding the pandemic, why are our students still faring poorly?

First, we continue to underspend in education, even if the Department of Education (DepEd) and other agencies get the lion’s share of the annual budget. This is a pity, since Figure 2 shows that there’s a correlation between math performance and cumulative spending per student.

Figure 2.

Second, the Philippines ranked third in terms of the percentage of students who say they didn’t have enough money to buy food, and as a result didn’t eat at least once a week in the past month. How can we expect students to learn if they’re hungry?

Third, Filipino students continue to face myriad challenges in and out of school, such as bullying, distraction from digital devices, lack of teachers, and poor parental involvement.

There’s so much to unpack in the 2022 PISA report. I encourage you to read the full report (two volumes), but here’s a useful factsheet for the Philippines.

Another wake-up call

Back in December 2019, I said that the PISA 2018 results should be a wake-up call for Filipinos. The newest results should try to wake us up again.

In all fairness, the government has not exactly been sleeping. In fact, it has initiated programs to try to abate the continuing learning crisis.

For instance, DepEd conducted the National Learning Camp in the middle of 2023. It’s a volunteer program where teachers are encouraged to help elementary and high school students catch up in English, Science, and Math. This is intended to happen at the end of every school year.

Meanwhile, in August, the Department of Education also launched its new Matatag Curriculum, which aims to decongest the old K-12 curriculum by 70%. Children these days are expected to master too many “learning competencies” in each school year, and the new Matatag Curriculum aims to streamline these competencies and focus on the most important ones.

There are new research papers, too, showing that relatively inexpensive interventions – such as supplementary lessons sent to students via SMS messages and phone calls, as done by economist Noam Angrist and his colleagues – can work wonders to improve students’ test performance. What this tells us that combatting learning losses is not impossible.

Having said all this, it will take many years (if not decades) for these and other interventions to bear fruit and make a dent on our students’ performance in standardized tests such as PISA.

Even education policymakers are under no illusions. DepEd Undersecretary Gina Gonong said, “Our education system is stable and resilient. Of course, there’s much to be desired. Maybe, a few more cycles of PISA and we can see improvements.” Meanwhile, Alexander Sucalit, also of DepEd, said: “If we follow the computation (of PISA) with caveats…we can see that [we] are around five to six years behind.”

The first thing in solving the crisis is admitting it. If anything, I’m glad to see that education policymakers are much less defensive now about the learning crisis – a stark contrast to a few years back, when education officials aggressively downplayed PISA and similar international assessments. The renewed honesty offers a bit of fresh air.

Still, I think more action will arise if we continue to emphasize that the continuing learning crisis is nothing short of a national emergency. The last thing we want is to be desensitized or lulled into a false sense of complacency.

Filipinos should demand greater, more urgent action. Our nation’s future will continue to be bleak unless we do something substantive to stop the learning crisis in its tracks. – Rappler.com

JC Punongbayan, PhD is an assistant professor at the UP School of Economics and the author of False Nostalgia: The Marcos “Golden Age” Myths and How to Debunk Them. JC’s views are independent of his affiliations. Follow him on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ Podcast.

1 comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Be The Good] What should the incoming DepEd secretary prioritize?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/newsletter-sonny-angara-july-3-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=298px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

Indeed, “Filipinos should demand greater, more urgent action.” But can we expect urgent actions from the DepEd Secretary who is so busy with her quarrel against a certain “Tambaloslos” and spying on the whole DepEd bureaucracy if there are officials, teachers, and students who are Communists?