SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

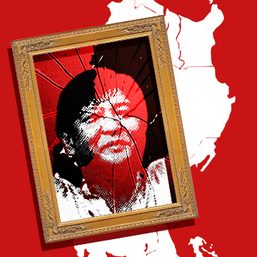

![[Newspoint] Cronyism in the second coming](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/07/tl-cronyism-in-the-making-July-15-2022.jpg)

In Philippine politics, cronyism became established as a practice in the Martial-Law regime of Ferdinand Marcos, 1972-1986. In fact, when you say “cronyism,” the association instantly inspired is with Marcos. And, not surprisingly, his son, a teenager who grew up to full adulthood in the very house from which his father presided and devolved power to a coterie of lieutenants, is not only defining his own presidency by the same practice but sourcing cronies from the families who colluded with his father and, in at least one case, enlisting the exact same crony.

Right upon taking office, Ferdinand Jr. began surrounding himself with an inner circle of such characters. Remulla, Ople, Estrella, Lagdameo-Floirendo – these are only some of the crony names. But one name rings a particularly haunting bell, and the man still answers to it, himself: Juan Ponce Enrile, Ferdinand Sr.’s chief martial-law enforcer.

Coming across, for his wily ways, as a man for all seasons of the odd sort, it was Enrile who faked his own ambush to give Ferdinand Sr. his pretext for Martial Law, then plotted against him, and, on being found out, switched sides, but only to return in the end, fully rehabilitated, to the Marcos fold. He is now, at 97, legal adviser to Ferdinand Jr.

Possibly the only other extant, first-ranked, but ever faithful lieutenant to Ferdinand Sr. is Estelito Mendoza, his solicitor general. He, too, would be likely enlisted in this second coming, if not for any useful capacity he might still possess – he is 92 himself, after all – at least for old time’s sake. In fact, he helped defend his old boss’s son against suits questioning his eligibility as a presidential candidate. But if his post-facto comments are any indication of the measure of his residual capacity, it doesn’t look much.

The suits were founded on a law that disqualifies convicts from elective office – Ferdinand Jr. is a convict himself, as a tax dodger. The Supreme Court took up his case not after he had filed his certificate of candidacy, not during his run, but after he had been proclaimed; and it ruled for him. Asked by the press for his reaction, Mendoza didn’t seem to do justice either to the court or to himself. He predicated the ruling not on any legal points, but on a circumstance of fate he himself found unbelievable.

“What clinched it,” he said, was his client’s “incredible margin” in the election.

Coming hot on the heels of that judicial victory, which eliminated the last obstacle to Ferdinand Jr.’s presidential installation, Mendoza’s words would seem only to reflect a renewed sense of power and impunity. But despite their utter lack of such legal erudition as might have been expected supplied by a man of his reputation – or is it because he felt so secure he could afford to be mindless? – those words do tend to go around well.

Among certain lawmakers, the reaction is remarkable for the sense of opportunism it exudes. They are proposing cutting the President’s term from six to five years but allowing reelection and lengthening the terms for other elective officials. There’s your match to Mendoza’s smug mindlessness.

Much is made of the point that sitting officials are not covered by the proposed change. It’s a joke. It makes no difference how often one is elected or how long one sits each term, not in a society like ours, where public office, to a monopolistic degree, is a dynastic preserve. Here, dynasties dominate elections, therefore dominate political and economic life, therefore are able to perpetuate themselves in wealth and power. Meanwhile, without patrons to make them cronies, the poor are perpetuated in privation.

If Ferdinand Jr. was well taught in anything, it was in exploiting the desperation of the poor for a quick fix to their miserable lives. And he promised them precisely that, doing so with his own amorphous catchword. Where his father preached “discipline” as the path to prosperity (“Sa ikauunlad ng bayan, disiplina ang kailangan”), he preached “unity” (pagkakaisa). At least during the campaign, he did keep the flock funded and fed – and fooled.

A more scrupulous campaigner would be hard put to sell to the desperate the more truthful scenario – that in a society so lopsided as ours it will take generations, even with good governance and generous private philanthropy, to make resources and opportunities go around with any measure of fairness. And to have the poor endure privation with moral equanimity (or, meekness, if you want to be literally, biblically correct), so that they may inherit the earth, constitutes absolute mockery in the face of plunder that goes unpunished, as in the precise case of the Marcoses.

All the poor ask of the earth is a decent living and dwelling, and when it is denied them the mockery is raised yet to celestial levels; redemption becomes attainable only through pain and death.

Now, you tell me what the poor’s chances are under this or any other Marcos. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Newspoint] What, me worry?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/09/what-me-worry-september-23-2022.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Closer Look] ‘Join Marcos, avert Duterte’ and the danger of expediency](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/TL-trillanes-duterte-expediency-june-29-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Newspoint] A Freedom Week joke](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/20240614-Filipino-Week-joke-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Rappler’s Best] Fasten seatbelt, Mr. President](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/fasten-seatbelt-mr-president-edit.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=235px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Power of mimicry: How human rights are covertly undermined in PH](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/duterte-marcos-human-rights.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Vantage Point] BBM Year 2: Hits and misses](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/thought-leaders-marcos-hits-and-misses.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=277px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[WATCH] #TheLeaderIWant: Filipino voters sound off on community issues a year before 2025 elections](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/filipino-voters-sound-off-on-community-issues-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=276px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Bodymind] Forgiveness, Enrile, and Bongbong Marcos Jr.](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/forgiveness-enrile-bongbong-march-6-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=411px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Bodymind] Juan Ponce Enrile’s hundred years of happiness](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-enrile.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=233px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[In This Economy] Small wins matter in the fight against Martial Law denialism](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/fight-against-martial-law-denialism-February-23-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=225px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[EDITORIAL] Juan Ponce Enrile: 100-year-old chameleon](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/animated-juan-ponce-enrile-100-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] A classic Duterte misdirection or power move?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/tl-duterte-misdirection-power-move-June-27-2024-revised-02.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=195px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Does VP Sara Duterte have a game plan?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/sara-duterte-game-plan-june-25-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] A political earthquake? Sara Duterte fails to seize narrative](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/thought-leaders-political-earthquake.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.