SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] Enewetak, Paradise Lost: Enewetak and its people](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/05/Screen-Shot-2022-05-02-at-5.00.44-PM.png)

The following is the 31st in a series of excerpts from Kelvin Rodolfo’s ongoing book project “Tilting at the Monster of Morong: Forays Against the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant and Global Nuclear Energy.“

Perhaps DNA shared through my Ilocano half compels me to care so deeply about Enewetak and its people, to linger so long over four forays to tell their story…

From 1946 to 1958, the US conducted 67 nuclear-weapon tests on Enewetak and Bikini atolls in the northwestern Marshall Islands. Enewetak lies 2,650 km east of Samar. What happened to all the radioactive debris should concern Filipino readers, because the North Equatorial ocean current flows westward a slow but steady one third to a half kilometer per hour through the Marshalls toward the Philippines. In 2014, Chinese scientists found plutonium isotopes from the tests in the Pearl River Estuary in Guangdong, northwest of Luzon.

Atolls

The green dots scattered throughout the equatorial western Pacific in this map are atolls, rings of shallow water with small islands. Each atoll is being built by coral reefs that started growing in the shallow water surrounding a mid-ocean volcano. Charles Darwin, the giant of biology, was also an excellent geologist. In 1842 he explained that the volcano subsides slowly enough for the corals to build themselves up fast enough to keep living in the warm, sunlit waters. Corals are animals that depend on pastel-colored algae to photosynthesize their food, and algae must have sunlight.

How did Darwin know? Atoll-building is a process. The Pacific displays many examples of its various stages, the three basic ones in the top panel of the illustration. Darwin’s simple but brilliant insight was to recognize that they represent stages of a process:

First, corals attach themselves to a slowly subsiding volcano, in the shallow, sunlit water that fringes it.

As the corals keep building upward to remain at the sunlit surface, the volcano subsides until only its tip remains above the sea, enclosed in a shallow lagoon by an offshore circle of coral that we call a “barrier reef” because it shields the volcano from the waves.

When the volcano has entirely subsided below the sea the barrier reef has become a true atoll, a shallow coralline ring surrounding the lagoon. The top of Enewetak’s ancestral volcano began to be buried sometime between 40 and 45 million years ago; now it lies under coralline rock more than 4,500 feet thick! This works out to sinking, countered by coral growth, at rates of about a quarter inch or half a centimeter per year.

Darwin didn’t know why the volcanoes subside; we learned why only in the late 1960s, with the plate-tectonic theory. We discussed that theory in Foray 8. Here, let’s just say that the “lithosphere,” Earth’s thick, rocky rind, continuously splits apart at an oceanic ridge. There, molten magma rises from the Earth’s interior, cools, and solidifies, adding to the lithosphere at both sides of the split. The two sides keep moving away from each other to make room as the process continues.

Volcanoes are the highest places of the hot, new lithosphere. Some stick up out of the water as islands. As the new lithosphere moves away from the ridge, it cools, shrinks, and subsides. And so the volcanoes sink, but slowly enough so the corals can keep pace, growing upward to remain sunlit.

The people of Enewetak

A shallow oval about 40 kilometers long by 28 kilometers wide, Enewetak Atoll gets its name from the southernmost and largest of its 40 tiny islands. “Enewetak” means “island that moves,” likely because of an ancient, long-forgotten, navigational misadventure.

The total area of all the Enewetak islands is less than six square kilometers or 600 hectares – two and a quarter square miles. Enewetak Island has an area of about two square kilometers; Enjebi Island in the north is second largest, with an area of only 0.7 square kilometer. The rest each average only about 10 hectares or 24 acres.

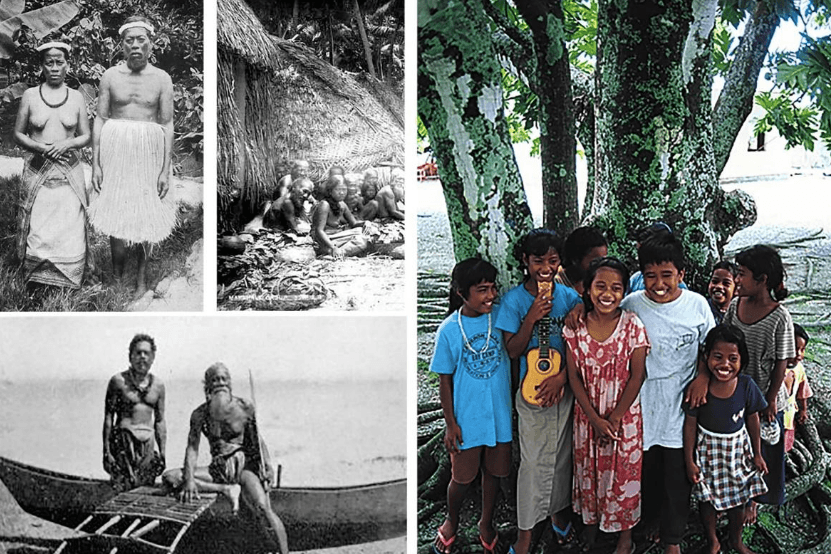

Most of the inhabitants on the two largest islands respectively called themselves the dri Enewetak and dri Enjebi, dri meaning “people o.f. Like Filipinos who they closely resemble, the people of Enewetak Atoll migrated from Southeast Asia starting about 3,000 years ago, in waves each lasting centuries. We stopped in the Philippines; they kept going east.

Long before Enewetak and the 28 atolls to the southeast were named the Marshall Islands after an English sea captain, their inhabitants called them Jolet Jen Anij, “The Gifts from God.” And before Europeans visited the atolls, they were indeed close to paradise on earth.

Over the millennia, the people established sustainable populations and lifestyles in harmony with their oceanic environment. Land was very scarce and prized. But its ownership was matrilineal – handed down from mother to daughter, even though the Iroij (chiefs) and Alap (clan heads) were male.

I believe a culture that respects its women tends to be more nurturing of the environment and more peaceful, even though there are accounts of deadly fights with foreign sailors over cultural misunderstandings. For the most part, the Marshallese are friendly and caring. They freely share among family and friends and warmly welcome strangers – values necessary for survival on small, widely separated islands.

The earliest photographs captured the Marshallese in traditional garb. Now, of course, they dress much like Filipinos.

The ocean and trade winds moderate the hot, humid climate. Typhoons visit Enewetak every several years, but the people clearly knew how to survive them.

Life was not easy; but after all, what would Paradise be without meaningful and soul-satisfying work? That was raising and gathering food. Fish and shellfish abounded in the lagoon and reefs. People foraged sustainably for fruit and vegetables, skillfully navigating their canoes among the tiny, uninhabited isles strung so many kilometers apart.

Coconut crabs and sea turtles were good sources of protein. Breadfruit trees, used to make canoes, also bore fruit that taste like fresh bread when cooked. Pandanus, bananas, papayas, taro, arrowroot, and sweet potatoes were also cultivated. Coconut palms were everywhere, but were not much used as food. The people raised chickens and pigs.

The first Europeans to visit the island paradise were 16th century Spanish explorers, who introduced unfamiliar diseases that killed many of the natives. So much for paradise…

The Spaniards in Manila galleons plying between Mexico and the Philippines became very familiar with the Marshalls. In 1874 Spain claimed them, but ruled loosely, and in 1885 sold them to Germany.

German corporations propagated coconuts on the Enewetak islands in large plantations for commercial copra. They used conscripted native labor; how humanely, I can’t say.

When World War I began, Japan wrested control of the islands from Germany, and after the war in 1920 the League of Nations formalized its Japanese ownership. Preparing for World War II, the Japanese began constructing airfields on the Marshalls in the 1930s, including one on Enjebi.

In February 1944, American forces took Enjebi and Enewetak islands after bloody battles with the Japanese.

After WWII the United Nations made the Marshall Islands and other Micronesian island groups into the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, entrusted to the United States as administrator.

The US did not “administer” well, we learn in our next foray. – Rappler.com

Born in Manila and educated at UP Diliman and the University of Southern California, Dr. Kelvin Rodolfo taught geology and environmental science at the University of Illinois at Chicago since 1966. He specialized in Philippine natural hazards since the 1980s.

Keep posted on Rappler for the next installment of Rodolfo’s series.

Previous pieces from Tilting at the Monster of Morong:

- [OPINION] Tilting at the Monster of Morong

- [OPINION] Mount Natib and her sisters

- [OPINION] Sear, kill, obliterate: On pyroclastic flows and surges

- [OPINION] Beneath the waters of Subic Bay an old pyroclastic-flow deposit, and many faults

- [OPINION] Propaganda about faulting, earthquakes, and the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant

- [OPINION] Discovering the Lubao Fault

- [OPINION] The Lubao Fault at BNPP, and the volcanic threats there

- [OPINION] How Natib volcano and her 2 sisters came to be

- [OPINION] More BNPP threats: A Manila Trench megathrust earthquake and its tsunamis

- [OPINION] Shoddy, shoddy, shoddy: How they built the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant

- [OPINION] Where, oh where, would BNPP’s fuel come from?

- [OPINION] ‘Megatons to Megawatts’: Prices and true costs of nuclear energy

- [OPINION] Uranium enrichment for energy leads to enrichment for weapons

- [OPINION] Introducing the nuclear fuel cycle

- [OPINION] On uranium mining and milling

- [OPINION] Enriching and fabricating BNPP’s uranium fuel

- [OPINION] Decommissioning BNPP, and storing the nuclear dragon’s radioactive manure

- [OPINION] So how much greenhouse gas does nuclear power really generate?

- [OPINION] Getting up close and personal with the atom, and its nucleus that powers NPPs

- [OPINION] The nucleus and isotopes: Why BNPP needs Uranium 235, Not Uranium 238

- [OPINION] What you should know about radioactivity

- [OPINION] Uranium mine waste and the weird idea of half-life

- [OPINION] How nuclear power plants work: Hot monster piss from Morong

- [OPINION] What if there was a spent-fuel pool accident at the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant?

- [OPINION] Nuclear weaponry, its radiation, and human health

- [OPINION] What Chernobyl could have taught us, but hasn’t been allowed to

- [OPINION] Activating BNPP would give cancer to workers and adults living nearby

- [OPINION] Activate BNPP? You could increase childhood cancers in Bataan and beyond

- [OPINION] The Hanford Site: Where nuclear pollution began and still reigns

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Who decides whether Bataan should go nuclear?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/08/imho-bataan-nuclear-powerplant.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=271px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Nuclear energy should not become major part of Philippine energy system](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/01/nuclear-energy-january-26-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=205px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.